“Today I wanted to share my indignation with regards to the African Union’s silence. Those people who are dying on the beaches – and I measure my words – if they were white, the whole world would be shaking! But since they are blacks and Arabs, it costs us less to just let them die!

If we wanted to save people in the Atlantic, in the Mediterranean, we could afford it. But we prefer to let them die first before we do anything. It is almost as though ‘letting them die’ is used as a deterrent, to stop the influx of migrants.

Well let me break it to you: it does not dissuade anyone! When someone leaves their country with failure in mind, that one might find the danger absurd and thus avoid it. But for those who leave their country for survival, those who consider that the life they have is worthless, their strength is unmeasurable, because they are not afraid of death! ”

These words were spoken on a French television network in April 2015 by a panellist in a debate with a very provocative theme: ‘Should we welcome or not all the misery of the world?’.

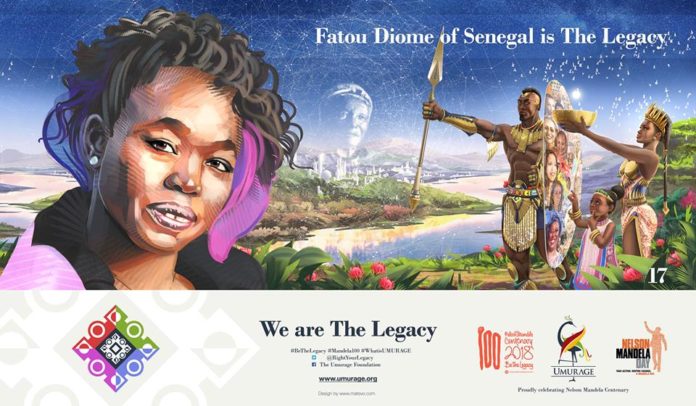

And the words I have transcribed here are just a small fragment of her entire intervention. The voice of this Franco-Senegalese author born in a small island of 20.000 inhabitants near the town of Fatick in Senegal, instantly and incontestably conquered the world and have become since one of the strongest voices of the voiceless in this ongoing and so called ‘migrant crisis’.

Her comments have gone viral and continue to circulate on the web, and that three years after the debate on France 2! Everything she said, the accuracy and her choice of words, the power of her argument and the way she does allow cynical remarks to stop her, resonated with people of in the world, especially people of African descent.

She has become, unwittingly, the de facto spokesperson of anyone who has ever been by these continuous discussions where Africans and migrants of all origins who venture into this desperate journey of the Mediterranean, are rarely invited if ever to the table to participate in such debate where their fate and future are the topic of the day.

Today I am inspired by Fatou Diome of Senegal. Fatou was born in 1968 on the small island of Niodior, in the Saloum delta, in southwestern Senegal. Born out of wedlock by two 18-year-olds in a conservative Muslim community that condemned their relationship, little Fatou was raised by her maternal grandmother, Aminata.

Fatou describes her grandmother as a pragmatic woman whose only priorities were to feed her, care for her and prepare her for a life without trouble, nothing more. Her grandmother came from another time, a time where girls had no other ambition than to get married and start a family.

Fatou had other aspirations for herself. She didn’t accept those traditions that relegated women to the kitchen and other house chores. From her grandmother’s house, Fatou could see the local primary school and she dreamed of being like the other children she saw there. But her grandmother did not want to hear anything about her getting an education.

In the morning, Aminata brought the little girl with her to her vegetable garden and they spent hours watering the vegetables. But as soon as her grandmother went back to the house to take care of other household chores, the little girl ran away and went to school.

“I would stay in the back of the classroom, making myself invisible, but the teacher sent me away.”

That didn’t stop her from coming back, again and again. Finally, seeing how determined the girl was and knowing that her grand-mother would end up finding out her granddaughter was schooled in secret, the teacher decided to meet her and try to convince her to allow Fatou to continue her studies.

Her grandmother eventually gave in and accepted the 7 years old girl choice, and the following year, she officially enrolled her in school.

Fatou never begrudged her grandmother for resisting to put her in school. She knew that her grandma loved her more than anything in the world and only wanted what she taught was best for her, a better life than her mother did, and she did not understand what education was about.

For Fatou, education was everything: school is where she discovered the French language and even as a young child, decided to one day become a teacher.

Since her small village does not have any secondary school, Fatou was sent at the age of 13 to live with relatives in the neighbouring city of M’Bour. They were supposed to help her complete her education, but it was quite the opposite.

“They treated me as their maid. I was told: today, you are not going to class, you have some laundry to do! So, at 14, I left and rented a small room, which I paid with little odd jobs. ”

Fatou beginned what she will later described as a ‘nomadic’ life, doing odd jobs to finance her dream of having a degree. Somehow, she managed to finish her secondary studies at the M’Bour’s High School. Although she recognizes the value of education, for her, it is this part of her teen years when she had to fend for herself that really forged her character.

“The streets ! When I was a teenager, I rented a room on my own. Obviously, when you live like this, you are confronted with the shear brutality of this society, it is unmasked, cold, and you must face it as it comes. ”

Far from breaking her, her solitude freed her mind, teaching her to question the world, and question adults and their responsibilities in the ills of society.

After high school, Fatou went to Gambia, a neighbouring country of Senegal, where she worked as a maid. With the money she earned, she returned to Dakar to enrol at the University Cheikh Anta Diop , my own alma mater. Coincidentally, I was studying on the Senegalese campus, I might have crossed her with ever knowing it.

Passionate about the French language, she dreamed of becoming a French teacher. It never crossed her mind to migrate and leave for Europe, till she met and fell in love with an expatriate, a French man. At 22 years old, she married him and followed him to France, in the Alsace region.

But far from being a beautiful fairy tale, her love story quickly turned sour. She will describe her relationship with a lot of humour later. “It was a casting error,” she says.

When she entered this relationship, it did not occur to her that it would matter to anyone that their couple was of mixt colours. In fact, she did not see her husband as someone with ‘different skin’. But others around them in her new-found land were not as colour-blind as she was. Her husband’s family treated her particularly badly, and unfortunately, her marriage could not sustain the constant pressure and negative environment.

In 1994, the 26 years old divorced and found herself practically homeless, a time that will remind her of her teen years, when she decided to leave her foster family to be on her own. And similarly, to those days, she did not allow herself to be discouraged by her circumstances. She went on to look for employment, only finding odd jobs to earn a living. And as in the days of M’Bour, Gambia and Dakar, she put everything she earned, no matter how small, into her education.

This will last six years, six years during which she went to the faculty at the University of Strasbourg while working a s a maid during her free time. She was so determined to get out of poverty and never to depend on anyone else for her survival that she continued to do these odd jobs even when her exceptional academic career earned her a job as a teacher assistant while she completed her graduate studies.

You probably think that a young student who spends days and nights preparing for a PhD, doing research for her thesis, spending days teaching classes and doing odd jobs would never find time to do anything else ?

Well our dear Fatou managed to find time to pursue a passion she had since her teenager year, when she was living in a little room in M’Bour: writing.

“I did not come to writing, writing came to me. I started writing when I left my village, I was thirteen. Because of I had to go and stay away from home to study, I often felt lonely, so I read a lot. Reading emboldened me to write short stories and it came like that, little by little . I was very young when I started writing and I have never stopped since. I just did it without really knowing where it would lead me. ”

Fatou found a way to transcribe her love for life and her revolt about the world’s injustices, and her daily experiences as someone who was living the setbacks of this European dream so hard to acquire. She channelled all these emotions and experiences in short stories revolving around the theme of the immigration, seen in the eyes of a girl who resembled her and who grew up from a story to another.

In 2001, while completing a doctorate of modern literature on the theme of ‘Travel, exchange and education in the literary and cinematographic work of Sembène Ousmane’, she published ‘National Preference’ (La Préférence National’), a collection of all the short stories had written for years.

‘The National Preference’ has been well received literary critics. But her breakthrough would come a couple years later when she published her debut novel ‘The Belly of the Atlantic’. Her book gained traction and made the name Fatou Diome became a household name in literary circles in France and around the world.

Here again, Fatou drew on her own life experiences to tell the story of migration as seen by Africans.

“Attracted, then filtered, parked, rejected, sorry. We find ourselves the unwilling participants of the world of travel”, she writes in this book which has been a literary success since its publication – with more than 200,000 copies – and started what some call today the ‘Diome phenomenon’.

“I was tired of all these clichés: immigration is not just poor exploited people, it’s not always that. Immigration is also people who leave their countries in search of emancipation, who leave in the name of their freedom … who leave for many other reasons that the host society does not necessarily perceive. For sure, there are people who leave for economic reasons, but others leave more for ‘life’ reasons.

I also wanted to talk about the relationship between immigrants living in Europe and their families back home. We are still talking about undocumented migrants, but we do not know why they left. We do not know what they are going through when they go back home, and I wanted to reveal these aspects. ”

Her promotional tour was most successful. Fatou Diome seduced the public with her charisma, her outspokenness, her ease with the words and her way of getting you to see what had been in front of you all this time but to which you had never really paid attention to: the dreams of all those people whose suffering and misery are the only thing we see.

From being a student who works as a maid to pay for her studies to becoming a successful author, now that’s a fairy tale, although Fatou doesn’t like to see it like that.

Over the last 15 years, Fatou Diome has continued to write critically acclaimed books and articles that continued to unveil the world of migration.

In the years following the publication of this novel that opened the worlds of French literature, Fatou Diome has gradually become the voice of reference for immigration and integration in France.

And since April 2015, when she spoke in that television debate on France 2, the voice of Fatou Diome, and not only her texts, has crossed the borders of France to land in the most remote corners of the world, including the small village of Niodior she left when she was 13 years old.

Her grandmother, who was still living on the island, ended-up hearing her grand-daughter’s name in the media, which worried her a lot, not knowing what it was all about.

“What did you do?” She would ask her when she called. For the old lady, people are only talked about you like that when they are in trouble.

But Fatou reassured her: “No grandmother, I’m not in trouble!”

And to prove her that all was ok, Fatou took the time to translate each of her books in their native language, the Serere language of Senegal, to share with her grandmother a little of this world she discovered some forty years ago, when she walked through the door of Niodior Primary School.

I cannot count the number of times friends have sent me the video of her intervention in the show ‘Ce soir ou jamais’ (‘Tonight or never!). And every time I get it, I take a moment to listen to it again, fascinated by her eloquence and the way she manages to say all that I have in mind, always to the point, never letting herself to be carried away in hollow arguments.

I will not tell you more. Today, I just wanted to reveal a little about the life of this wonderful woman whose video must have come through you through your favourite social network.

Fatou Diome must be listen to and read, she can best be appreciated when you hear her speak her words in her own voice. I encourage you to look for footages of her interviews and conferences, and if you have time, look for her books and discover the verve of this exceptional author and activist.

I do not know if you will necessarily like what she says but I can assure you that she will not leave you indifferent.

“You will not stay like little goldfish in the European fortress. Today, we know that Europe will never be spared as long as there are conflicts elsewhere in the world, Europe will never be opulent again as long as there is misery elsewhere in the world . So, let’s find a collective solution or move out of Europe if you want because I am here to stay.”

Well said, Fatou! You are the voice of those voiceless, those whose story is reduced to a few cold statistics and of whom are only allowed pictures of, crammed by hundreds on these boats of misery, or photos taken while they are almost drowning in the sea, surrounded by pieces of their broken life boats and lifeless bodies floating on these waters far from home. Through you, we are sure that not only is their story heard but that their message of hope is listened to and acted upon.

Right Your Legacy, Fatou Diome! #BeTheLegacy #WeAreTheLegacy#Mandela100 #WhatisUMURAGE

Contributors

Um’Khonde Patrick Habamenshi