By David Himbara

On August 30, 2017, Rwanda’s security forces in civilian clothing brutally assaulted the home of Diane Shima Rwigara. Since then the whereabouts of Diane, her mother, sister, and two brothers remains a mystery. The Kagame regime is holding the family in a secret location. Two years ago, Diane’s father died in a mysterious car accident. Soon after, the family’s hotel was demolished. The family was made to pay the cost of the demolition.

So what is Diane Shima Rwigara’s crime that might explain the latest assault? Diane took an unprecedented step to stand against Kagame for the August 2017 presidential elections. Her electoral issues included the restoration of fundamental freedom and liberties, and rejection of authoritarianism. Diane did not run for the Rwandan presidency, however. She was blocked. But she persisted in articulating her views as a private citizen. And now she is paying a heavy price.

While the world is shocked by Kagame’s relentless brutality, do not expect any reaction from Kagame’s British friends. For the British political elite, the Rwandan dictator Paul Kagame offers a Faustian bargain: Overlook my brutal behaviour, and I will offer you a model for social and economic development in an African nation.

As with Dr. Faustus, who sold his soul to Satan, Kagame’s British admirers will be bitterly disappointed.

While sacrificing human rights on the altar of socioeconomic development, Kagame is delivering neither democracy nor prosperity.

Kagame’s descent into a vicious and murderous autocrat is well documented – even by the governments that support him most – the US and the UK. This is amply demonstrated by US State Department and UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office reports. Kagame’s critics die under mysterious circumstances, even in exile. Opposition political parties and independent newspapers have been suppressed. Many Rwandans have fled the country, while many more have been scared into silence. That is how Kagame wins elections by 99%. And, under an amended constitution, Kagame is free to rule Rwanda until 2034 – after having been at the helm since 1994.

What is the basis of the British appeasement and fascination with the Rwandan dictator? While the British political elite boasts that Kagame has achieved “tremendous progress,” Rwanda’s performance remains mired in mediocrity.

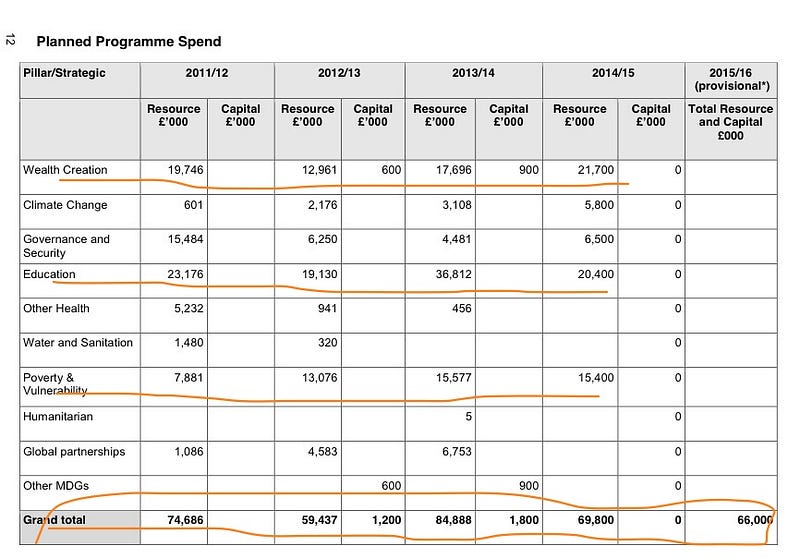

Take a look at Rwanda’s education sector which absorbs the bulk of British aid. As indicated in DFID table, between 2011/2012 and 2014/2015, £100 million British taxpayers’ money was poured into the education sector.

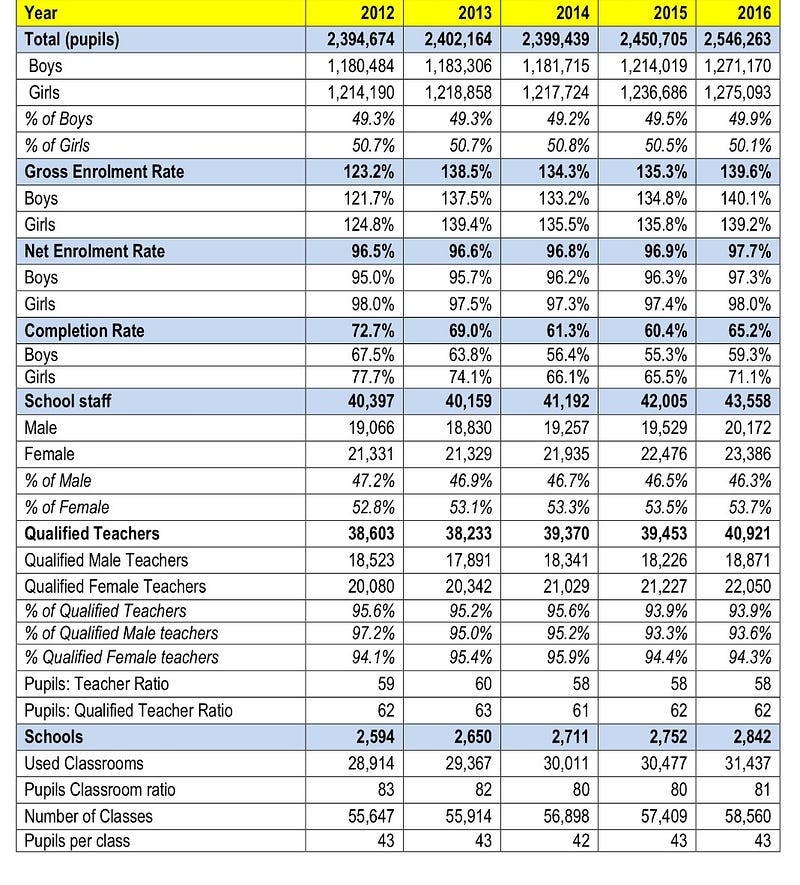

But far from moving forward, Rwanda’s education is a disaster. The Kagame government’s own statistics shown below tell the story.

The dismal state of the primary school education in Rwanda is illustrated by the following realities:

- Completion rate was 72.7% in 2012, but dropped to 65.2% in 2016.

- Pupil/qualified teacher ratio was 62 in 2012, and remained 62 in 2016.

- Pupils per class was 43 in 2012, and remained 43 in 2016.

- 31.6% of primary schools in Rwanda have access to electricity.

- 35.7% of primary schools have access to tap water.

Secondary school education is in a much worse situation as demonstrated by the following indicators:

- Net enrolment rate was 36.4% in 2013, and dropped to 32.9% by 2016.

- Percentage of qualified teachers was 69.3% in 2013, and dropped to 69.2% in 2016.

- 46% of secondary schools are connected to national electricity grid.

- 39% of secondary schools connected to piped water.

Back in 2012, an independent evaluation of DFID’s support of three East African countries, including Rwanda, had already made the following conclusion:

The main outcomes of DFID’s education assistance in our three case study countries in East Africa have been rapid improvement in access to primary schooling…We are nonetheless concerned that the quality of education being provided to most children in these countries is so low that it seriously detracts from the development impact of DFID’s educational assistance. To achieve near-universal primary enrolment but with a large majority of pupils failing to attain basic levels of literacy or numeracy is not, in our view, a successful development result. It represents poor value for money both for the UK’s assistance and for national budgets.

As shown above, by 2016, the quality of DFID-supported education in Rwanda was in fact worse than in 2012.

The failure of Kagame’s Faustian bargain – trading democracy for development and ending up with neither – should come as no surprise to students of history and human nature.

A dictator who can’t be questioned; a population that lives in fear; and a foreign donor that has chosen appeasement – these are not the formula for social and economic development. In Africa as elsewhere, people do their best work in an environment of freedom, not fear. As for the British political elite – its a pathetic case.