(Reuters) – In forested hills in eastern Congo, rebels are honing their ambush skills to prepare to face a new United Nations force which has a mandate to go on the offensive.

“Destroy the enemy. Cause fear and stop his patrols,” a rebel officer wrote on a blackboard as he instructed uniformed M23 fighters at a camp seized from the government in Democratic Republic of Congo’s eastern borderlands.

In the latest effort to bring peace to a region riven for years by conflict over ethnic rivalry and mineral riches, the United Nations is deploying a 3,000-strong brigade of African troops with a mission of neutralizing armed groups such as M23.

Approved by the Security Council in March for “targeted offensive operations”, the brigade from South Africa, Tanzania and Malawi is the first to be created within a traditional peacekeeping force. A 17,000-strong existing U.N. force, MONUSCO, has struggled to maintain security in eastern Congo.

If the M23 rebels, who emerged last year from a Tutsi-led rebellion in 2004-2009, fear the new U.N. Force Intervention Brigade, they are not showing it.

They routed U.N.-backed Congolese troops and briefly seized the North Kivu provincial capital of Goma in November, an embarrassment for President Joseph Kabila and the United Nations.

M23 spokesman Colonel Vianney Kazarama said the rebel group, which is demanding political concessions from Kabila’s government, had no plans to attack U.N. peacekeepers. But if targeted, it would respond.

“You’ll see, we’re going to capture them, destroy their equipment, march over their forces,” Kazarama said.

At the captured government camp, rebels paraded and put on a show of hand-to-hand combat in the bush grass.

Military experts say the brigade could find itself severely stretched in its mission to neutralize and disarm the M23 and other armed groups.

M23 is well-trained and well-armed. U.N. experts say it is backed by Rwanda and Uganda although both countries deny it.

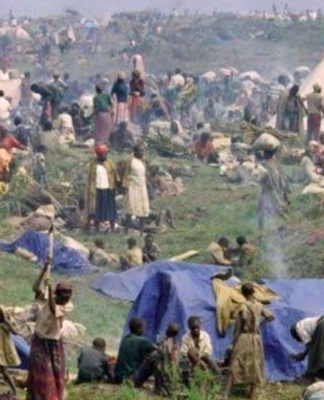

FDLR rebels, the remnants of Hutu killers who carried out the 1994 genocide of Tutsis in Rwanda, and other militias also roam the green hills and valleys of North Kivu.

“It’s a complex mission. From a tactical point of view this is a logistical nightmare because you don’t know who’s who in the zoo from one day to the next,” said Helmoed Romer Heitman, a South African military analyst.

He questioned whether the U.N. brigade, which will include about 1,000 South African troops and an equal number from Tanzania and Malawi, would big and strong enough.

“The overall U.N. mission is not properly conceived. I think the force is too small and there is a certain amount of wishful thinking,” Heitman told Reuters in Pretoria.

“PEACE AT ANY PRICE”

South African military spokesman Xolani Mabanga said the numbers were in line with recommendations.

“We are happy with the size of the force,” he said.

South Africa’s armed forces are already smarting from the deaths of 13 soldiers in March in Central African Republic when anti-government rebels confronted a 200-strong South African contingent deployed there under a defense agreement.

This has increased the political sensitivity of South Africa’s participation in the Congo.

M23 have shown signs of being rattled, appealing against South Africa’s involvement with a mixture of threats and entreaties to pan-African solidarity.

“They’re scared of the brigade. They call meetings to tell the population to reject it,” student Guillaume Muchuti told Reuters in the M23-held town of Rutshuru, north of Goma.

Tanzania also brushed off threats from M23 that it will target its soldiers if they join the U.N. mission.

“We are not going to Congo as lords of war, we are going there as advocates of peace to help our neighbors,” Tanzanian Foreign Minister Bernard Membe told parliament.

M23 officials privately admit their force’s numbers have been reduced by months of infighting between rival factions. Congo’s army estimates the rebels’ strength at around 1,000.

This led to one leader, Bosco Ntaganda, surrendering to the International Criminal Court to face war crimes charges.

Despite seizing tons of ammunition and scores of vehicles when it occupied Goma, M23 is running short of cash to pay its fighters, rebel sources say. MONUSCO says it has received a steady stream of deserters.

Kabila’s government, whose weak and indisciplined army has struggled to contain rebels in the east and is accused by rights groups of rapes and abuses against civilians, welcomes the new U.N. brigade.

Government spokesman Lambert Mende says Kinshasa would like a negotiated peace with M23, but, failing that, hopes the African peacekeepers’ robust mandate can have a real impact.

U.N. officials caution that while the intervention brigade is expected to be a deterrent to violence in North Kivu, it will not be a “magic wand” for bringing peace.

“It’s not as if they’re going to come and start shooting on the first day. The objective is to contain and neutralize and disarm armed groups. If we can do that without firing a shot, everyone will be very happy,” said Alex Queval, head of MONUSCO in North Kivu province.

NEED FOR POLITICAL SOLUTION

Former Irish president Mary Robinson, who was appointed U.N. special envoy to the Great Lakes region in March, toured last week to encourage implementation of a U.N.-mediated peace plan for the eastern Congo signed by 11 countries in February.

“There’s no doubt these armed groups need to be dealt with, but I think it’s important that this does not become a focus on a military solution,” she said in Goma.

M23 was not part of the February pact and its own separate peace negotiations with the Congolese government have stalled, amid signs that Kinshasa is reluctant to implement vague promises of national political dialogue and decentralization.

Maria Lange, country head of advocacy group International Alert, says that even if the U.N. brigade makes short-term gains, this may not guarantee lasting solutions. The brigade would allow the government to pursue a military solution.

“They’ve been liberated from the obligation to actually conduct talks and address underlying governance problems,” Lange told Reuters. “This brigade risks at best being ineffective, or at worst, will lead to an escalation of the situation.”

There are fears too the government will not carry out much-needed reforms of its security forces, Lange added.

U.N. troops have faced protests in the past by Congolerse civilians angry about what they see as the peacekeepers’ failure to protect them from abuses by armed groups.

“The last hope we have is for this brigade, we’re waiting for them. But I don’t have much faith,” said Innocent Bisimungu.

His parents were hacked to death by Hutu rebels in 1998 and now he lives in a zone under the control of the Tutsi-led M23.

“I was born in conflict and I grew up in conflict. We’ve never known anything else,” he said wearily.

(Additional reporting by Peroshni Govender in Pretoria and Ed Cropley in Johannesburg; Editing by Pascal Fletcher and Angus MacSwan)