Imagine you were born in the UK towards the end of the second world war. Imagine your family went to start a new life in New Zealand. Imagine that, once an adult, you move back to the UK to study classical music. Imagine you build a successful career, playing with the most renowned directors in the world. Imagine that some 20 years down the road, you hear about a musical project in Soweto in dire need of help. Imagine you organise fundraisers on their behalf, start sending money and visiting them in South-Africa but you realise they need more than a few visits a year. How far will you go to help them? How much will you invest yourself in the future of these gifted youth living in a country barely emerging from the apartheid era?

Imagine you were born in the UK towards the end of the second world war. Imagine your family went to start a new life in New Zealand. Imagine that, once an adult, you move back to the UK to study classical music. Imagine you build a successful career, playing with the most renowned directors in the world. Imagine that some 20 years down the road, you hear about a musical project in Soweto in dire need of help. Imagine you organise fundraisers on their behalf, start sending money and visiting them in South-Africa but you realise they need more than a few visits a year. How far will you go to help them? How much will you invest yourself in the future of these gifted youth living in a country barely emerging from the apartheid era?

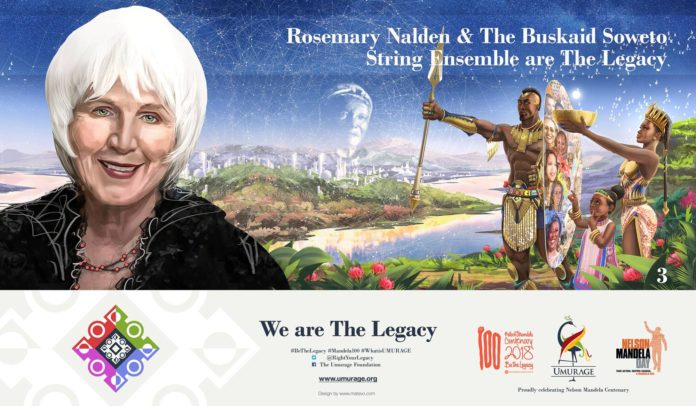

Today, I am inspired by Rosemary Nalden of the United Kingdom. Rosemary was born in the UK in the 1940’s. Even as a child, Rosemary was a very determined young girl, a quality she inherited from her father. Though this latter was orphaned at an early age, he managed to study music via correspondence courses. This might seem an obvious way to study nowadays, but it was a new modality for English universities in the post first world war era. He obtained two doctorates in music but ironically, he couldn’t land any academic post in Britain as he had never set foot in a classroom.

When Rosemary was 4, her father decided to move the family to New Zealand and try his luck at gaining employment in his dream field. It was the right move: her father was finally able to perform and teach music. He even went on to create the country’s first music conservatory.

“The pioneering thing, the madness, has been inherited,” she later shared.

After earning a Bachelor of Arts in Languages at The University of Auckland in New Zealand, Rosemary moved back to her native England to follow her father footsteps in the musical field.

The young lady, now 24, enrolled at the Royal College of Music in London, where she studied viola and singing. After graduation, she decided to stay in the United Kingdom and started a successful career as a freelance artist, playing with renown music ensembles such as John Eliot Gardiner’s English Baroque Soloists and Roger Norrington’s London Classical Players.

Parallel to her career as a performer, Rosemary taught music in her London apartment.

After 20 years of career and success on the music scene, her life seemed set and quietly heading towards a well deserved retirement. Yet everything was to change in 1991. An event or rather two events, two bizarre coincidences were going to make Rosemary rethink her life priorities. The first event: Rosemary heard a radio programme on BBC about a struggling music program in the township of Soweto, in South-Africa. It was a short clip on BBC Radio 4’s Today Programme but somehow it stuck to her mind.

The second event: a couple of months later, Rosemary read the same story of this struggling string project in Diepkloof, Soweto, in a paper she often read on Sundays, The Independent.

Though Soweto was some 9,000 kilometres from where she lived and was as foreign to her as a place can be, something in that story made her want to try and help them.

Of course, like everyone in the world in those years, she had heard of Soweto, the township of Johannesburg made famous for its resistance to the inhumane Apartheid system, but truth be told, she had never associated Soweto to classical music.

This double coincidence could only be fate, she thought! So she decided to act and help them. She called upon other professional musician friends and colleagues and asked them to join her in a busk to support the South-African musical project. For those unfamiliar with that strange word, a ‘busk’ simply means playing for money in a public place.

The response was overwhelming: 120 fellow musicians joined Rosemary and they went to play music in 16 train stations in the UK! In April 1992, Rosemary went to South Africa to give the school the 6000 pounds (roughly 10,000 USD) she had raised with her colleagues and discover who these musicians from the townships were.

She knew from her readings that Soweto, this township of almost 2 million people, was an impoverished community, but what she was to see was even worst than what she had imagined.

The project was located a community centre next to a makeshift transit camp for people who worked in the nearby mines in Johannesburg. The room where the children were learning music had a toilet with no doors, and Rosemary was shocked to see the constant movements of people from the nearby squats crossing the room to use the restrooms, which made her conclude that they were most likely the only toilets in the area.

This was way outside the comfort zone of this British lady from Hampstead. However, when the kids started playing, Rosemary was no longer distracted by those movements, overwhelmed as she was by the shear talents before her.

“I was fascinated by the whole phenomenon of these incredibly talented children who were so thirsty for violin lessons. I couldn’t turn back although I don’t remember making a conscious decision. I was just captivated and had this feeling that after having shown them what was possible I couldn’t walk away.”

The kids – and probably the whole neighbourhood – were also fascinated by her. Though Apartheid had officially ended in 1990, it was still odd for a white woman to visit a township.

“It was very, very unusual for a white woman to suddenly appear in a South African township. It was unheard of.”

After that initial visit, she went back to the UK and created a fund – the Busked Trust UK – to pursue her fundraising efforts. She also came back to visit them twice or three times a year to give classes for the next 3 to 4 years.

After a while, she realised that the funds she sent were misappropriated by the project, and that the kids were not getting the right support. When it became clear she could no longer support that cause, she made a big decision, probably the biggest decision of her life: she was going to start her own school.

And it was not about opening a school that she would run from London: she was intent on moving to Soweto and run the school herself. If anyone had ever told Rosemary that she would one day be running a school in a township, she would probably have called you crazy. But the sentiment that she belonged there, with those youth, sentiments raised by the 1991 radio show had only increased over the years.

In 1997, the white-haired violinist landed in South-Africa with her savings and a few instruments and never looked back. She managed to find a small room in the Presbyterian Church of Soweto and enrolled her very first students. The Buskaid Music School of Soweto was officially born.

While teaching came to her naturally, but she had to learn from scratch how to run a non-profit organisation, building a music school from the ground-up and fundraising a school budget (far different from busking for a music course). On top of that, she had to fight prejudice against negative perceptions of classical music, which was resented by many as it was reminiscent of the European heritage of a country that was painfully trying to come to terms with its recent history.

It was not easy to adapt to her new circumstances. It was a completely different culture, she was living away her family and friends and in much less comfortable conditions as what she was accustomed to. She was at times nostalgic of her past life, but all sadness vanished when she listened to her kids playing. She also gradually grew attached to her new neighbourhood, learning to appreciate the pride people took in their homes, despite their humbleness, and the extraordinary difficulties kids had to face every day with the rampant violence and the scourge of drugs very much symptomatic of those early post-apartheid years.

Buskaid started with 15 kids crowded in her little room at the Presbyterian Church. The room was so tiny, they had to go outdoors to play, which proved to be challenging during the long months of rain.

Fortunately, this situation only lasted two years. In 1998, the Church gave her a piece of land in the same neighbourhood and with the support of friends and corporate donors, Rosemary build a real school with seven studios, a music library and a large rehearsal room! Buskaid moved to the new location in 1999 and was able to immediately double the number of students.

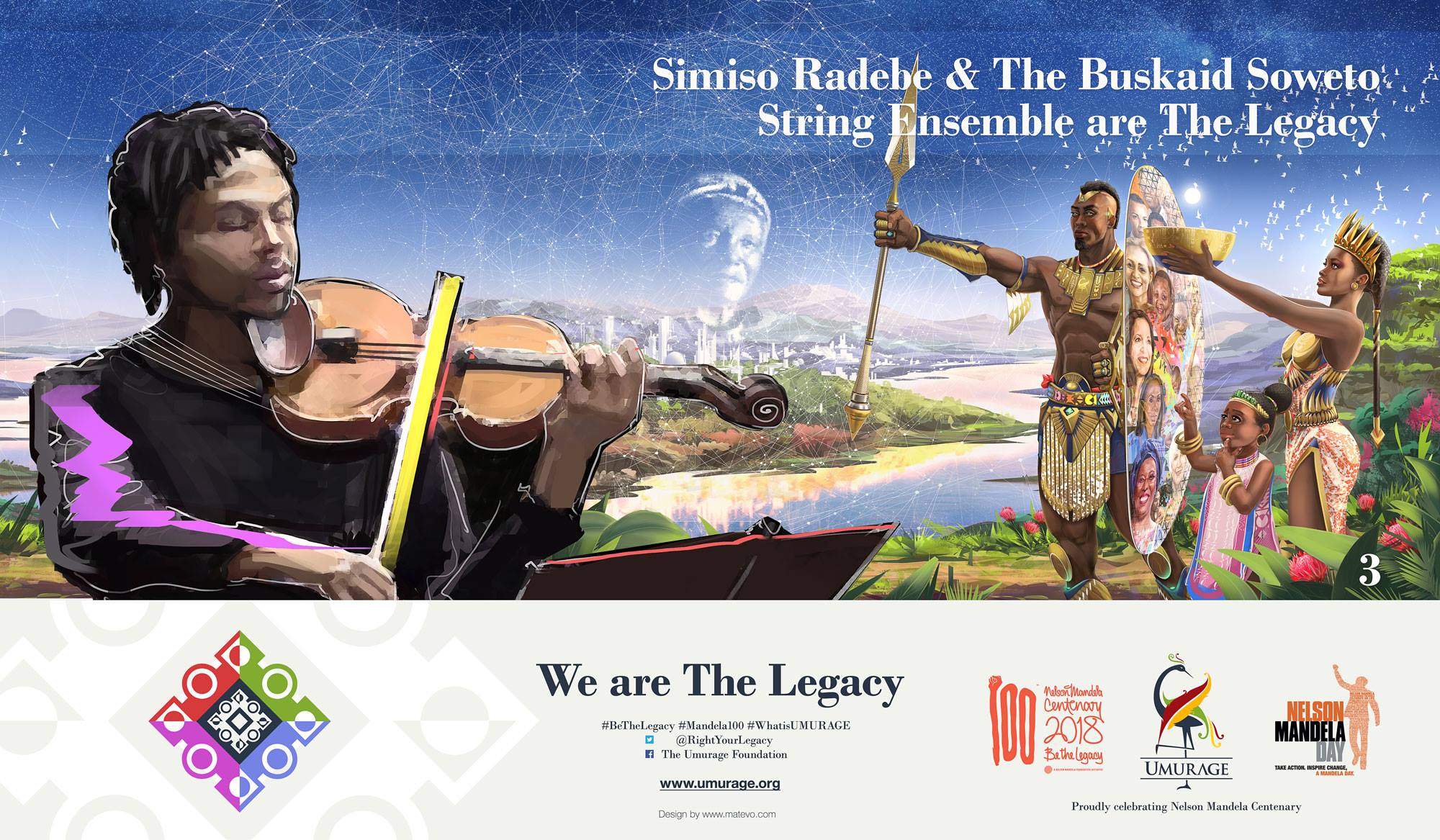

One of her first students at the new location was a boy called Simiso Radebe. His story seemed to capture all the tragedies and hopes of the Soweto community. At the early age of 8, Simiso knew he wanted to become a violinist. Rosemary never discovered how that idea came to the mind of this young child. Nothing said music in his life. He was born in a very poor family, with both parents unemployed, four brothers and sisters, one of them a drug addict, who slept on mattresses on the living room floor. Yet, one day, the young boy went and enrolled in a nearby music program and started learning violin.

He wasn’t satisfied with the quality of the teaching – yes, at 8 years old! – so he went to look for another program. He wasn’t satisfied there either and went looking for yet another program. That when he landed at Buskaid and met Rosemary Nalden for the first time.

Simiso was a very shy little boy, who didn’t talk much and didn’t know how to answer all the questions the white-haired woman asked him.

When he started playing, she was breathless! It was a real mystery to see this budding young genius, to whom no adult had ever spoken of violins, and whose parents, probably unaware of what a violin was, never helped to pursue his dream.

She took him under her wing. Ten years later, Simiso had grown into an accomplished violinist, was performing around the world and was teaching younger students at Buskaid. In 2010, at 19 years old, it is a completely transformed young man who enrolled in the Royal Academy of Music in London, all on his own merits!

But I am jumping too far ahead. Let’s go back at the beginning for a moment. One of the difficulties Rosemary had when she started the school was to find teachers. Though Mandela had become President, many white people feared retaliation from the blacks and she could only get one person – Sonja Bass, who is still with the school – to accept to come and teach in the townships.

She felt discouraged for a moment.

“We were settled in our new school, and these kids were coming all the time, but we couldn’t get teachers for them.”

Sonja Bass and Rosemary put their heads together they finally had a eureka moment: why not simply ask the senior students to take on that role? They sat with the youth and proposed a deal:

“We will teach you a very sophisticated skills, and in return would you like to come and help us teach?”

All the students agreed and rose to the occasion. Today, nine of its eleven salaried teachers are school alumni.

“I can say with confidence that they are amongst the best teachers in the world.”

The Buskaid model evolved over the year to include teaching skills for all the kids, no matter their age, so they can mentor the next classes.

Most of her students, like Simiso, come from extremely difficult background – drugs, abuse, AIDS, malnutrition, abandonment by one of the parents, etc. – but she doesn’t allow their circumstances to be an excuse to be less than the best they can be.

Rosemary’s goal is not to teach them string instruments to distract them from their surroundings. Her goal is to elevate them and groom them to perform on any stage in the world. To that end, strives to bring the school up to the highest international standards.

She also teaches them the fundamental values of community life: respect for oneself, respect for others, respect for the group. In addition, Buskaid offers its students medical, social and psychological support.

When she learns of problems at home, Rosemary goes to meet the families, in their home, ensuring the kids know the school is with them in all aspects of their lives.

She could not imagine doing things differently. Kids are really in the driver’s seat when you think about it. It is the kids who ‘called’ her to come to South-Africa. And since the very first day, it is always the kids and not their parents who come to enrol themselves at the school, something unheard of where she comes from.

Still, her criteria to take them in are very strict: demonstrate a true determination and musical sensitivity and have a talent ready to emerge. In turn, the school will nurture that talent and allow them to express their fullest potential.

The school, which started with less than 20 students, has nowadays 125 students enrolled year round, ranging in age from six to thirty-four, all of whom are drawn from the less privileged local community. In 1997, the school owned fewer than twenty instruments; Buskaid now owns nearly 100 instruments.

Many of her students have been awarded scholarships at international conservatories. Some have managed to join the prestigious Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester or the Royal Music Academy in London.

The Buskaid Soweto String Ensemble has gained international recognition, through their performances and the albums they’ve been recording since 1998.

In 2007, British filmmaker Mark Kidel produced a documentary of the Buskaid story, ‘Soweto Strings’, which won several awards and was shown world-wide, giving them even more visibility.

In 1999, Buskaid won the Arts and Culture Trust (ACT) Award for best Cultural Development Project. In 2002, Rosemary Nalden was awarded an MBE in the Golden Jubilee Queen’s Birthday Honours List, in recognition of her work with Buskaid. An MBE is one of the highest distinctions in the UK; it rewards contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations, and public service outside the Civil service.

In 2003 she received a Distinguished Alumni Award from her former university, The University of Auckland, in New Zealand, and in 2006 was highly commended in the category of Community Builder for the Beacon Fellowship Awards. In October 2007 Buskaid won the ACT Arts Education Project Award.

In 2009 the Buskaid Ensemble was listed by Gramophone Magazine as one of the world’s ten most inspiring orchestras, alongside the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, the London Symphony Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, the East West Divan Orchestra and the Simón Bolivar Youth Orchestra. In 2013, Rosemary Nalden was awarded an Honorary Membership of the Royal Philharmonic Society, a rare and highly prestigious Award which has been granted to fewer than 140 musicians in the past 200 years.

The Ensemble has played five times under the baton of Rosemary former mentor, Sir John Eliot Gardiner. It has performed several times in the presence of Nelson Mandela, for Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, HRH Prince Charles and other members of the British Royal family, as well as for many distinguished foreign dignitaries, including the former First Lady of the United States of America, Mrs Michelle Obama.

The 75 years old is still at the helm of her school in Soweto, travels the world with her ensemble, to the great enchantment of audiences around the world.

And she has no plans of retiring any time soon.

Right Your Legacy, Rosemary Nalden! You are the Legacy! #BeTheLegacy#WeAreTheLegacy #Mandela100 #WhatisUMURAGE

Contributors

Um’Khonde Habamenshi

Lion Imanzi