By The Rwandan Lawyer

Introduction

Seized to rule on the issues of prior compensation required by the constitution and the law governing expropriation, the judge of Nyarugenge Intermediate Court deviates its role of judging submitted case on its merits and recommends conciliation, an alternative unexpected by the parties. What is driving this denial of justice? The present article intends to analyze the ins and outs of this compromising situation.

1.Facts

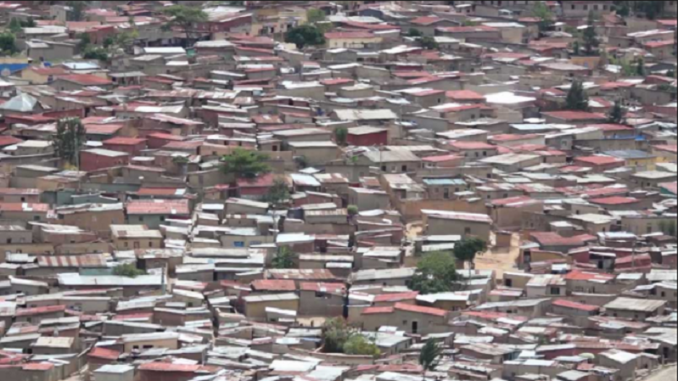

The Nyarugenge Intermediate Court has recommended a mediation between Kigali and residents of Kangondo and Kibiraro villages in Nyarutarama Cell, Remera Sector, Gasabo District.The recommendation was made on Thursday, 6th 2021 during the hearing of a case involving the City of Kigali and about 25 residents of Kangondo and Kibiraro villages known as Bannyahe area.It is a case that has been postponed four times for various reasons, including the Covid-19 epidemic and the fact that the city of Kigali had not yet found Lawyers. The residents sued the city of Kigali after refusing the compensation they had been given to relocate to another place. The demolition of houses in the area which is considered one of the areas in a disorganized and unfavorable housing in the city of Kigali, and modern building construction began in September 2017.After refusing the compensation, they immediately filed a lawsuit in the Nyarugenge Intermediate Court accusing the city of Kigali of giving them unfair compensation adding that the city of Kigali should compensate them in accordance with the law. All 25 residents were given the same case number with the same defendants.

On Thursday, a panel of three judges and a court clerk entered the courtroom, and the presiding judge first asked if all the parties were present.After finding that all are present including the accused the hearing startedThe City of Kigali in this case is represented by Me Safari Vianney and Me Shema Gerard and the residents of Kangondo and Kibiraro are represented by lawyers including Me Buhuru Pierre Célestin, Me Songa Jean Paul, Me Ndihokubwayo Innocent and Me Umararangu Priscila.

The judge spoke to both sides about the benefits of resolving disputes through consensus, rather than continuing in court.The parties agreed to settle the dispute amicably, electing Nshimiyimana Didace, who chaired the hearing and the Vice President of the Nyarugenge Intermediate Court, as their mediator.As the mediation process began, Kigali City Attorney Me Safari Vianney immediately requested the mediator to postpone it and resume it next week so that they could first report it to the Kigali City Council. Judge Nshimiyimana Didace immediately adjourned the mediation to resume on May 13, 2021 at 8:00 AM. Me Buhuru Pierre Celestin told the media that the fact that they were advised to adhere to the mediation was a good thing because what is needed is to resolve the dispute amicably.

2.Analysis

The decision rendered by the intermediate court of Nyarugenge pushes to note a denial of justice and ruling beyond what was requested.

2.1.Denial of justice

According to the Article 9 of the law no 22/2018 of 29/04/2018 relating to the civil, commercial, labor and administrative procedure, a judge adjudicates a case on the basis of relevant rules of law. In the absence of such rules, the judge adjudicates according to the rules that he/she would establish if he/she had to act as legislator, relying on precedents, customs, general principles of law and doctrine. A judge cannot refuse to decide a case on any pretext of silence, obscurity or insufficiency of the law. A judge may encourage parties to use conciliation if he/she believes that conciliation is the most appropriate way to resolve the dispute. He/she may him/herself mediate between the parties or help them find a mediator of their choice and postpones the hearing for the entire duration of conciliation. A judge can in no way base on foreign courts’ decisions or legal doctrine if such decisions or doctrine conflict with public order or the Rwandan legal system.

Law No. 2007-1787 of December 20, 2007 characterized the denial of justice by the fact that judges refused to respond to requests or failed to try cases in good condition and in turn to be tried. The same text specifies that the State is civilly responsible for the damages convictions that are handed down on the basis of denial of justice, except for its appeal against the judges who have committed them.

Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights, states that “everyone has the right to have their cause heard fairly, publicly and within a reasonable time, by an independent and impartial tribunal established by law, which will decide either on disputes over its civil rights and obligations, or on the merits of any criminal charge directed against it “. This provision served as the basis for the recognition, by the European Court of Human Rights, of a right of access to justice, of the right to a judicial remedy.According to this judgment, “The principle that a civil dispute must be able to be brought before a judge is one of the fundamental principles of universally recognized law; the same is true of the principle of international law which prohibits the denial of justice. Article 6.1 should be read in their light. If this text were to be regarded as relating exclusively to the conduct of proceedings already instituted before a tribunal, a Contracting State could, without infringing it, abolish its jurisdictions or exempt from their jurisdiction the settlement of certain categories of civil disputes to entrust it. to bodies dependent on the Government. Such hypotheses, inseparable from a risk of arbitrariness, would lead to serious consequences contrary to those principles and which the Court cannot lose sight of … In the eyes of the Court,it would not be understood that article 6.1 describes in detail the procedural guarantees granted to the parties to a civil action in progress and that it does not first protect what alone makes it possible to benefit from them in reality: access to judge. Fairness, publicity and speed of the trial are of no interest in the absence of a trial. “

If the impossibility for a party to access the judge responsible for ruling on his claim and exercising a right which falls within the scope of international public order constitutes a denial of justice founding the jurisdiction of the French court when there is a connection with France, the mere holding by a French company of part of the capital of a foreign company does not constitute a connection for denial of justice.

Whether or not the proceedings have been duly initiated by a party, any request brought before a court obliges the judge seized of it to rule. The absence of a decision terminating the proceedings taken within a reasonable time or taken with a delay which would not be justified by the specific circumstances of the proceedings (overcrowding of the rolls, successive references requested by the parties , lack of due diligence by the requesting party, non-delivery of the documents requested by the court, case of legal suspension of the proceedings, execution of investigative measures .) and which would reveal a desire of the judge not to rule, would constitute one of the cases of opening of the “taken to task“. It would engage the responsibility of the State. As for the assessment of the duration of proceedings having had the same object, it was necessary, not, to consider the duration of each procedure taken in isolation, but to take into account the space of time which was necessary to obtain the final solution.

Regarding the course of an international arbitration procedure, the First Chamber of the Court of Cassation ruled that the impossibility for a party to access the judge, even arbitral, responsible for ruling on his claim and thus exercising a right which came under international public order enshrined in the principles of international arbitration, constituted a denial of justice justifying the international jurisdiction of the French judge.

2.2.Trend to rule extra petita or ultra petita

As per Article 10 of the law no 22/2018 of 29/04/2018 relating to the civil, commercial, labour and administrative procedure, a judge may not decide more than he/she has been asked to. In same context, Article 11 of this law states that a judge cannot base his/her decision on the facts which have not been raised during the hearing. Neither can he/she decide a case on the basis of personal knowledge of the case. Usually used in relation to a judgment of the court which exceeds even that which was asked for, such as a damage award which is in excess of what a plaintiff requested.

An ultra petita decision is not good law and is typically and successfully appealed on that ground.

The ultra petita rule highlights the importance of good pleadings as a Court cannot generally give a litigant more than what they ask for. If a personal injury is alleged but no damages pleaded, awarding damages might be ultra petita. The reality is that in most cases, a judge will nudge a litigant along to make up for any fatal deficiency at trial such as:

Conclusion

The option adopted by the judge proves without doubt that the latter was under pressure of instructions of his authorities or the higher public powers given that the state was fearing to lose the case which should be a reference for further claims and may refrain it to ever resort to those maneuvers of illegal expropriation and in-kind compensation rejected by its alleged beneficiaries.