In April, Faustin Rukundo received a mysterious call over WhatsApp from a number he did not recognise.

He answered, but the line was silent and then it went dead. He tried calling back but nobody answered.

He didn’t know it but his phone had been compromised.

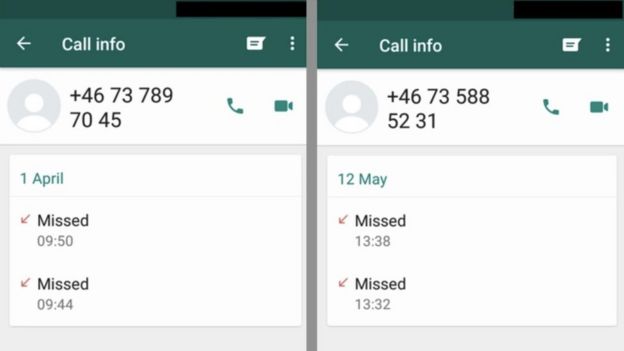

As a Rwandan exile living in Leeds, Mr Rukundo was already privacy conscious. He searched for the number online and found the dialling code was from Sweden.

Strange, he thought. But he soon forgot about it.

Then the number called once more. Again nobody picked up.

There were also missed calls from other numbers he did not recognise and he began to get worried about his family’s safety, so he bought a new phone.

Within a day, the unknown number called again.

“I tried to answer and they hung up before I heard any voice,” Mr Rukundo told the BBC.

“Whenever I called back, no-one answered. I realised something was wrong when I started seeing files missing from the phone.

“I spoke to my colleagues at the Rwanda National Congress and they too had similar experiences. They were getting missed calls from the same numbers as me.”

The Rwanda National Congress is a group that opposes the Rwandan regime.

It was not until May, when Mr Rukundo read reports that WhatsApp had been hacked, that he realised what had happened.

“I first read the story about the WhatsApp hack on the BBC and thought, ‘Wow, this could explain what’s happened to me,'” he said.

“I changed my phone and realised my mistake. They were following my number around and putting the spy software on each new device by calling the same number.”

For months, Mr Rukundo was convinced that he and his colleagues were some of the estimated 1,400 people targeted by attackers exploiting the flaw in WhatsApp.

But it was only confirmed to him this week following a call from Citizen Lab in Toronto.

For six months, the organisation has been working with Facebook to investigate the hack and find out who was affected.

Researchers there say: “As part of our investigation into the incident, Citizen Lab has identified over 100 cases of abusive targeting of human rights defenders and journalists in at least 20 countries across the globe.”

Mr Rukundo’s profile as an outspoken critic of the Rwandan regime is consistent with the sort of people who were targets for this spyware.

It was allegedly built and sold by the Israel-based NSO Group and sold to governments around the world.

Hackers used the software to spy on journalists, human rights activists, political dissidents and diplomats.

Mr Rukundo says he has not had any calls since the original hack, but the experience has made him and his family feel paranoid and scared.

“Honestly, even before they confirmed this, we were gutted and terrified. It looks like they only bugged my phone for around two weeks but they had access to everything,” he told the BBC.

“Not only my activity during that time but my whole email history and all my contacts and connections. Everything is watched, the computers, our phones, nothing is safe. Even when we talk, they could be listening. I still don’t feel safe.”

Mr Rukundo fled Rwanda in 2005 when critics of the government were being arrested and jailed. He says he fought to have his wife released after she was kidnapped and detained for two months on a family visit in 2007.

Facebook, the owner of WhatsApp, is attempting to sue the NSO Group.

The NSO Group denies any wrongdoing.

In court documents, Facebook accuses the company of exploiting a then-unknown vulnerability in WhatsApp.

The app is used by approximately 1.5 billion people in 180 countries.

The service is popular for its end-to-end encryption, which means messages are scrambled as they travel across the internet, making them unreadable if intercepted.

The filing at the US District Court of Northern California describes how the spyware was allegedly installed.

The powerful software known as Pegasus is an NSO Group product that can remotely and covertly extract valuable intelligence from mobile devices, by sharing all phone activity including communications and location data with the attacker.

- WhatsApp discovers ‘targeted’ surveillance attack

- WhatsApp sues Israeli firm over phone hacking claims

In previous spyware attacks, victims have been tricked into downloading the software by clicking on booby-trapped web links.

But with the WhatsApp hack, Facebook alleges that it was installed on victims’ phones without them taking any action at all.

The company says that between January 2018 and May 2019, NSO Group created WhatsApp accounts using telephone numbers registered in different counties, including Cyprus, Israel, Brazil, Indonesia, Sweden and the Netherlands.

Then in April and May, the victims were attacked with a phone call over WhatsApp, it is claimed.

The filing says: “To avoid the technical restrictions built into WhatsApp Signaling Servers, defendants formatted call initiation messages containing malicious code to appear like a legitimate call and concealed the code within call settings.

“Disguising the malicious code as call settings enabled defendants to deliver it to the target device and made the malicious code appear as if it originated from WhatsApp Signaling Servers.”

The victims would be completely unaware that they had been bugged. In some cases the only thing they noticed were mysterious missed calls in WhatsApp logs.

The document states that Facebook:

- believes the hack was an abuse of its computer network

- wants an injunction stopping the NSO Group having any access to its platforms.

- accepts that NSO Group was allegedly carrying out the hacks on behalf of its customers, but Facebook is going after the company as the architects who created the software

NSO Group has been accused of supplying the spyware that let the killers of journalist Jamal Khashoggi track him down.

NSO Group denies involvement in that incident and says it will fight these latest allegations.

“In the strongest possible terms, we dispute today’s allegations and will vigorously fight them,” the company said in a statement to the BBC.

“The sole purpose of NSO Group is to provide technology to licensed government intelligence and law enforcement agencies to help them fight terrorism and serious crime.”

Source: Joe Tidy, Cyber-security reporter, BBC News