By The Rwandan Lawyer

The 2015 expropriation law grants the State the power to interfere in private property rights for a public interest, provided that there is a payment of a fair compensation, that is, an indemnity that is equivalent to the market value of the land and related properties. The compensation can be paid in a monetary form or in any other form mutually agreed upon by an expropriator and an expropriated person . In addition, national housing and human settlement policies recognize the rights of local communities to participate in making and implementing decisions and plans related to urban (re)development, including the resettlement of displaced property owners.

Community participation in urban (re)development processes is a prerequisite for meeting processual and distributive aspects of spatial justice.. In expropriation and resettlement processes, processual aspects encompass negotiation on the compensation option between the expropriating agencies and property owners, and their direct collaboration in designing and implementing the resettlement plans. The distributive aspect includes the compensation for the acquired real properties at the market value; improved access to basic urban amenities and services for the resettled property owners; and their opportunities to reconstitute their livelihoods, that is, access to new jobs or income-generating activities. These aspirations are also well reiterated in the current regulations related to Kigali city (re)development, which legitimize resettlement as the compensation option for expropriated property owners . However, recent studies on Kigali city (re)development processes point out that expropriated people have been skeptical about the advantages of this form of compensation because it may not be carried out in a just way.. Nevertheless, there are no studies that fully ascertain justice aspects from the implementation of this form of compensation.. This study is, therefore, a contribution to bridge this knowledge gap. Its main objective is to evaluate if the in-kind compensation for expropriated real properties in Kigali city exhibits some trends of spatial justice in the related regulations as well as their implementation processes and outcomes. The pursuit of this objective was guided by the following research questions: Do regulations and practices governing the in-kind compensation option in Kigali city promote spatial justice? How can this compensation option be effectively applied to advance spatial justice for expropriated real property owners in Kigali city?

1.Facts

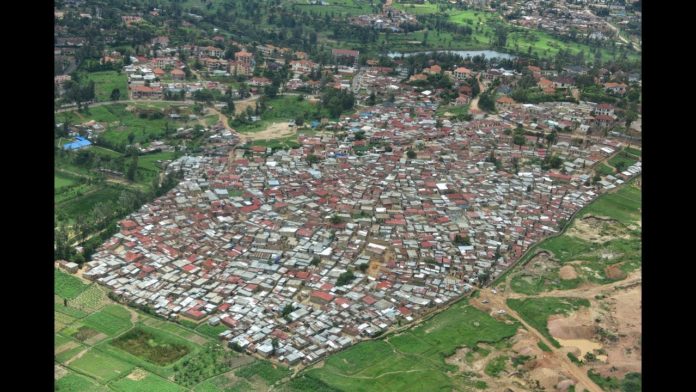

The City of Kigali announced that more than 1,100 households designated as located in wetlands and on dangerous slopes will be relocated as soon as possible as the rain continue to pound the soil since last year. This is a policy of City of Kigali and other national institutions to relocate people from high risk zones before these disasters can happen. While addressing residents of Kangondo 1, there was noted that though some of them have resisted being relocated, it is a responsibility of the government to protect citizens from any form of disaster.

Though the damage is visible for all to see, some of the residents do not want to move, seeking compensation first but district authorities informed them that the Government is working on alternative affordable housing for them. The houses are expected to be ready by June 2021.

The Gasabo district official said that a recent mapping exercise done by the City of Kigali showed that some settlements in the district are prone to disaster especially if the rains continue. They include parts of Nyarutarama, Kimihurura, Mulindi and Kagondo 1 where the relocation exercise began.

District authorities held discussions with Gasabo residents in locations which were found to be exposed to possible disasters and the district offered to support them in terms of immediate rent as alternative houses are being built.

According to the Mayor of City of Kigali, Pudence Rubingisa, 392 houses are being built for vulnerable households and should be complete by June.

In a briefing which brought together the Ministries of Local Government, Emergency Management, City of Kigali, Meteo Rwanda, Rwanda Water and Forestry Authority and Rwanda Environment Management Authority (REMA), this week the government said there is an urgent need to relocate at least 11, 000 households which are in imminent danger.

Other areas identified as prone to disasters include Mpazi Ravine in Kimisagara near Maison de Jeunes, Gikondo-MAGERWA, Kimihurura- Mu Myembe, Gikondo, Nyarutarama, Mulindi near Legacy Clinic, Poids Lourds wetland, Kangondo 1, Gatsata, Rwampara and Rugunga among others.

2.Analysis of issues

Despite these good outcomes, there are other aspects of spatial justice that show very low scores and tend to depict some patterns of spatial injustices in the implementation of the in-kind compensation.

2.1.Limited Evidence of Spatial Justice in the Implementation Processes and Outcomes of the In-Kind Compensation

we discuss the general problems identified during implementation processes of in-kind compensation and their implications on the livelihoods of expropriated property owners. These problems are linked with the unwillingness of expropriating agencies to negotiate with property owners on the compensation option and include them in the planning and implementation of resettlement processes. This resulted in the non-recognition of the basic needs and rights to employment and/or income-generating activities of these property owners, which can be well comprehended from a spatial justice lens.

2.2.Lack of Negotiation on the Compensation Options and Community Participation in the Resettlement Processes: Deficient Procedural and Recognitional Justice

Procedural and recognitional justice considerations contribute to fair negotiation with real property owners during the expropriation projects and their participation in urban space (re)development, which are a prerequisite to attaining just outcomes. Negotiation on compensation options and participation of expropriated people in their resettlement are their rights and factors for procedural and recognitional justice. These aspects of spatial justice should be embedded in the rules and processes of urban (re)development to reach fair and transparent decision and outcomes . The related forms of spatial justice received a score of 4.6 out of 5 for the rules dimension.. This finding is consistent with the Rwandan expropriation law, which recognizes the rights of property owners to negotiate on the compensation option, even though it does not entitle these people to participate in the planning and implementation of their resettlement process. Nevertheless, different policies and regulations related to urban (re)development such as the urbanization policy, national human settlement and housing policies, and laws related to land use planning and building development in Rwanda entitle the local community the rights to be engaged in all processes related to the design and implementation of urban (re)development plans..

However, there is criticism that these rights are not respected. Representatives of Kigali city and local government entities (like the districts and local leaders) are the main actors who implement the master and detailed plans of Kigali city, designed from 2008 to 2013 by independent consultancy firms without local community engagement . This practice has resulted in a top-down urban planning approach, which does not open the room for local community participation in urban space management. Yet, members of the sector and district councils represent the local community in making decisions related to local development, including the establishment of local development plans . However, this approach of Kigali city management was criticized by participants in our household survey who stated that their representatives do not advocate for their needs and rights during the approval of these local development plans. One of them argued the following:

“The members of the sector and district councils may not have power to influence the high-level decision makers who are responsible for the implementation of Kigali city master plan. They are informed about what has been planned and requested to communicate the information to the local community in the sake of compliance..

The lack of communicative and participatory urban planning is shown by the deficiency of the spatial justice frames related to negotiation and participation in the implementation processes of the expropriation in Kigali city. The non-recognition of property owners’ rights to negotiate the compensation options or participate in the valuation process is frequent in developing countries, such as Angola, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Lesotho, Nigeria, Thailand, and Zimbabwe. This happens when the expropriating agencies face a shortage of budgets and under-estimate the compensation in order to lower the cost of expropriation. Although there is no evidence for this practice in Kigali city, government officials implementing the master plan of this city do not clearly justify the reason for not negotiating with the property owners on the compensation option. They argue that negotiation and participation of property owners in expropriation, design, and implementation of their resettlement plans may be cumbersome and time-consuming because their expectations diverge from those of decision makers. During our interviews, one of these officials implementing the expropriation process stated the following:

“Property owners do not like to negotiate. They prefer to be compensated in a monetary form. Unfortunately, this compensation option does not help all of them to access new properties in Kigali city. They move towards the urban fringe where they informally develop new houses. This practice has to be discouraged. For the government as well as property owners, the best option which can promote their access to quality housing, basic urban amenities and their integration in the urban space is the resettlement (Interviews with local leaders, Kigali city authorities)”.

Despite this justification for not negotiating and collaborating with property owners in the expropriation process, these authorities do not provide any evidence about a failed attempt to use this approach. Nevertheless, negotiation and collaboration approaches have been applied without compromising the success of expropriation and resettlement projects in various countries such as Morocco, India, Sri Lanka, East Timor, and Pacific States. In Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Slovenia, and Germany, the expropriation process and the determination of compensation value for private real property involve negotiation and agreement between the property owners and the expropriating agencies.

The lack of compliance with these ethical frames during expropriation and resettlement of affected property owners in Kigali city has resulted in the construction of houses that do not fit the sizes of their families. An immediate consequence is overcrowded houses (like the studios) for 63% of expropriated households. This reveals the low level of compliance to spatial justice criteria in all its forms and dimensions, as shown by a moderate score of 3.1 at the rules dimension, which falls to 1.1 out of 5 for the processes and outcomes dimensions. The scores ranging between 1 and 2 indicate the lack of spatial justice aspects in rules and processes related to the resettlement of expropriated households, and the factor for developing small sized houses, which do not fit the number of people in each household. Another factor is the limited financial capacity of the expropriating agencies to develop big houses for these property owners, although the market values for these small houses are still higher than the values of expropriated properties. This aspect is discussed in detail in the next sub-section.

3. Proposed ways forward

3.1.Fair Compensation at market values is not always spatially just

As stated in Section (Compensation at the Market Value and Improved Quality of Housing Exhibit Various Patterns of Spatial Justice) and shown in Table 4, the in-kind compensation for expropriated property owners results in developing modern houses for which market values are higher than the values of expropriated properties. However, these high market values are not commensurate with the adequate housing, which is the basis for good housing conditions for the resettled people. An adequate housing unit is associated with its use-value. From a recognitional justice dialectic, access to a new house reflects just outcomes if this house can be used to meet the needs of the owners . In contrast, the provision of a housing unit that does not consider the household size reflects a deficiency in recognitional justice. This results in overcrowding conditions that will be observed in the developed houses, in relation to their sizes and number of rooms, which do not match the sizes of expropriated households. During our survey, some of these households critically questioned the number of bedrooms and overcrowding aspect of these new houses they are supposed to receive as compensation, as follows: “How can parents who have two or three children sleep in one-bedroom with their children? Each family should receive at least a house with different sleeping rooms for parents and children”.

Other people stated that their resettlement in apartments is not a good option, if they take into account the mean household size in Rwanda, which is close to five persons. One of the expropriated property owners who will receive a studio (as a compensation) mentioned the difficulties associated with its uses, as follows:

“Tell me (he asked me) how can parents and their children sleep together in a studio? Decision makers are aware that parents do not sleep with children who are over 3 years old. Our relocation in the studio is even disrespectful to parents since sleeping in the studio will unveil our private relationships to children”.

Although existing houses in the pre-relocation settlements are very small (between 26 and 42 square meters), 58% of households live in at least two bedrooms for the parents and children. Among the 18% poor households, each of them has one bedroom occupied by the parents and a sitting room that is also used as a bedroom for the children.. In this regard, one of the expropriated women who participated in our survey stated the following: “the expropriating agencies should bear the cost of a housing unit which can fit the size of each family if they really want to improve its living conditions”. She went on and argued the following: “If these agencies do not have such capacity, the compensation should be in monetary form so that we can move to other areas and develop other houses at our convenience”.

The arguments of these respondents concur with the general aspiration of spatial justice or international norms, which claim that expropriating agencies should pay enough to place expropriated people in the same or improved living conditions.

Generally, the consideration of procedural and recognitional justice aspects from the resettlement of expropriated property owners in Kigali city in relation to the overcrowding aspect of the houses they are supposed to receive leads us to posit that this compensation option is not spatially just. The lack of spatial justice is reflected in the non-participation of these property owners in the planning and implementation of their resettlement processes. This resulted in the development of new houses that do not fit their household sizes. This problem was discussed with one of the decision makers during our interviews. His responses were contentious, as he argued that, “the expropriated property owners whose family sizes do not fit within the developed houses have rights to rent or sell them to small or single families which can fit well in these houses”.

His argument contrasts with the urban development goals related to social inclusion and informal settlements growth mitigation in Kigali city. If expropriated property owners sell the new houses that they are supposed to receive, they may relocate themselves in the informal settlements and contribute to their spatial growth, which is already mushrooming and no longer tolerated by the current Kigali city zoning regulations. In addition, if they do not occupy the new houses in the resettlement site, this can result in their disintegration from the formal city and deprivation of access to basic urban amenities that the adopted in-kind compensation intends to tackle.

3.2.Options for promoting spatial justice in the implementation of in-kind compensation in Kigali city

In this section, we present and discuss three main options (compatible with the demands of spatial justice) through which in-kind compensation can be implemented, as suggested by the heads of households who participated in this study. These options include the combination of in-cash compensation and self-help incremental housing development in another residential site; social mix and participatory in-situ resettlement; and resettlement in the urban village and diversified dwelling units around business and services areas. Some of these options are reiterated in the current rules and strategic development plans related to both urban and socio-economic development in Rwanda. Applying them during the resettlement of expropriated property owners may result in spatially just outcomes in the broad context of inclusive urban (re)development.

3.3. The in-cash compensation and self-help incremental housing development: procedural, recognition, and redistributive justice

To cater for the problem associated with the habitability of housing units allocated to expropriated property owners in Kibiraro and Kangondo, a possible just option suggested by 96% of these people is the combination of the in-cash and in-kind compensation. It would consist of fair compensation in a monetary form for the houses and other developments on the land, and the provision of serviced land plots in another residential site that is close to employment opportunities such as commercial or industrial areas. As they stressed, the selection of this site should be carried out in a participatory manner, through collaboration between Kigali city authorities and property owners. Thereafter, expropriated people can incrementally develop their own houses, using the compensation paid for the non-movable properties. This option is commensurate with different forms of spatial justice such as procedural embedded in compensation at market value for these properties and engagement of property owners in developing their residential neighborhood, following a participatory planning approach of their resettlement.

Recognitional and redistributive justice are reflected in recognition of the expropriated property owners’ rights to produce their dwelling units, which are compatible with their family sizes. Redistributive and intra-generational justice are exhibited in the allocation of residential land plots to these people so that they can develop (through self-help construction) diversified dwelling units, aligned with their needs and financial capacities. However, finishing a self-help house may be di cult for the poor and very low-income categories. This can result in the transformation of the selected residential site into shacks or informal settlements. To minimize this risk, the implementation of the self-help housing development approach can be applied through a partnership of expropriated property owners with Kigali city authorities, urban planners, and other government officials who are engaged in the management of this city. Therefore, these actors can seek other forms of support (from local NGOs, international development agencies) that may consist of material or financial assistance to the poor and very low-income urban dwellers who may fail to develop the received land plots according to the proposed housing development plan. The financial support can also be provided by Kigali city and the central government, as reiterated in the NST1, and different strategic development plans of Rwanda. In the case in which it is difficult to implement the self-help housing development in partnership with Kigali city authorities and their representatives owing to their limited time, at least the resettlement plan of expropriated households should be designed in a participatory manner. Thereafter, it can be implemented through regular control by local leaders and professionals at a low-level of government who enforce local community compliance with the master and local development plans of this city.

3.4. Promotion of the social mix through the participatory in-situ resettlement

Social mix is among the options that can be applied to promote spatial justice with urban (re)development, through the integration of poor and low-income urban neighborhoods and their inhabitants in the formal city. The social mix approach is supported by 95% of households who

participated in this study, as it can enhance their formal integration in the urban space. Its application can result in developing dwelling units that are balanced in the needs of all categories of urban dwellers. This housing development option, which is acclaimed to be spatially just, is largely echoed in the work of Arthurson, Levin, and Ziersch. According to these scholars, the social mix is like a corridor for spatial justice flagship in the urban space (re)organisation when it consists of clearing and re-developing the declining poor and low-income neighbourhoods. One of its outcomes is the protection of these areas’ inhabitants against the displacement.. The social mix has been implemented in different ways. Its most common implementation practice has been termed the “organic mix”, consisting of developing mixed housing typologies that integrate various socio-economic groups in a spatially just and inclusive urban space. As Marcuse, contends, apart from advancing the equality in access to decent housing, the organic mix promotes access to basic urban amenities and services required for the welfare of all urbanites.

Although the existing literature shows that this urban (re)development option has mainly been implemented in developed countries such as The Netherlands, Australia, United Kingdom, USA, and Canada , it is among the options that can be applied to advance recognitional and redistributive spatial justice in Kigali city management. This option is reiterated in the urbanization policy, housing policy, and urban housing policy of Rwanda, as well as the master plans of Kigali city, whose goals include the integration of all categories of urban dwellers in the urban spaces through the development of mixed-income residential neighbourhoods. Its implementation requires a communicative and collaborative urban planning approach, embedded in procedural and recognitional justice, which allows for various categories of urban dwellers (poor, middle, and upper income groups) to interact and design urban (re)development plans for the creation of diversified residential neighbourhoods that permit their integration in the urban geography. These residential neighbourhoods should be connected through a fair provision of public facilities in order to minimise the risks of spatial segregation..

If the organic mix approach is used for the in-situ resettlement of expropriated property owners, it prevents their displacement through the redevelopment of their neighborhood, which can include the conversion of the existing single houses into low- and middle-rise apartments in order to optimize the use of suitable buildable land. In addition, it can preserve the social relations among these people and support their livelihood enhancement. We propose this urban (re)development approach in an attempt to mitigate various challenges such as the loss of employment opportunities that expropriated property owners may face after their o -site resettlement. In addition, this approach is among the informal settlement management options suggested by various studies on Kigali city. Its implementation requires the landscape and environment management operations to minimise the environmental hazards. However, construction works of new houses for the property owners in Kangondo and Kibiraro who participated in this study are almost finished. It is expected that these people will move into these houses by June 2020..Despite the current progress in their resettlement process, this study identified that it could have been possible to relocate these urban dwellers in one part of their neighbourhood, and thus reduce their displacement.

Conclusion

This study formulates some recommendations for preventing these unjust outcomes in further processes of resettling expropriated property owners. The pursuit of procedural and recognitional justice through active participation of property owners should be at the forefront in the expropriation process so that they can negotiate their compensation options. Participation and negotiation are the ladder for spatial justice in all processes of urban re-organization. They allow for recognition of the rights of all urban dwellers to urban resources, identification of their basic needs, and good decision-making processes that help to effectively meet these needs. Even if the needs of all people affected by these urban (re)development processes may not be met when the values of their properties are lower than the required financial resources for their effective resettlement, the negotiation and participation can at least result in a common consensus that establishes a balance between the basic needs of each party (the expropriating agencies and property owners) and the available resources. Therefore, the negotiation and participation approach can support the fairness of the established processes and reached outcomes. Expropriated property owners should also be actively involved in planning and implementing their resettlement plans, if the outcomes of the negotiation uphold for their resettlement as the compensation option. From the perspective of recognitional, redistributive, and intra-generational justice, greater consideration should be given to each household size and the dimension of the new dwelling units, as well as the aspects related to livelihood and income sources. These aspects can be dealt with through the in-situ resettlement or selection of resettlement locations with various employment opportunities. These resettlement approaches and the urban village suggested in this study have the benefits of helping to achieve a diverse social mix. Moreover, the combination of in-kind and in-cash compensation can mitigate the social and economic impacts of lost jobs, businesses, or income sources. Finally, partial loans for self-help housing development can provide expropriated households with more options in home size needed to prevent overcrowding and allow for the reconstitution of their businesses.