By David Himbara

Letter From Rwanda

Dear DH, please share your thoughts on the debate between His Excellency President Paul Kagame and Jon Clifton, the CEO of Gallup. They disagreed on Gallop’s World Happiness surveys. HE was initially pleased by Gallup’s survey which showed that 99% of Rwandans have confidence in the government. But the President denounced Gallup for ranking Rwandans among the world’s most miserable people. This is impossible, said HE, because Rwandans live in the world’s most improved conditions. Clifton’s response was that 2 billion people in the world are suffering from poverty, despite economic growth. Kindly share your views on this controversy.

Response to the letter from Rwanda.

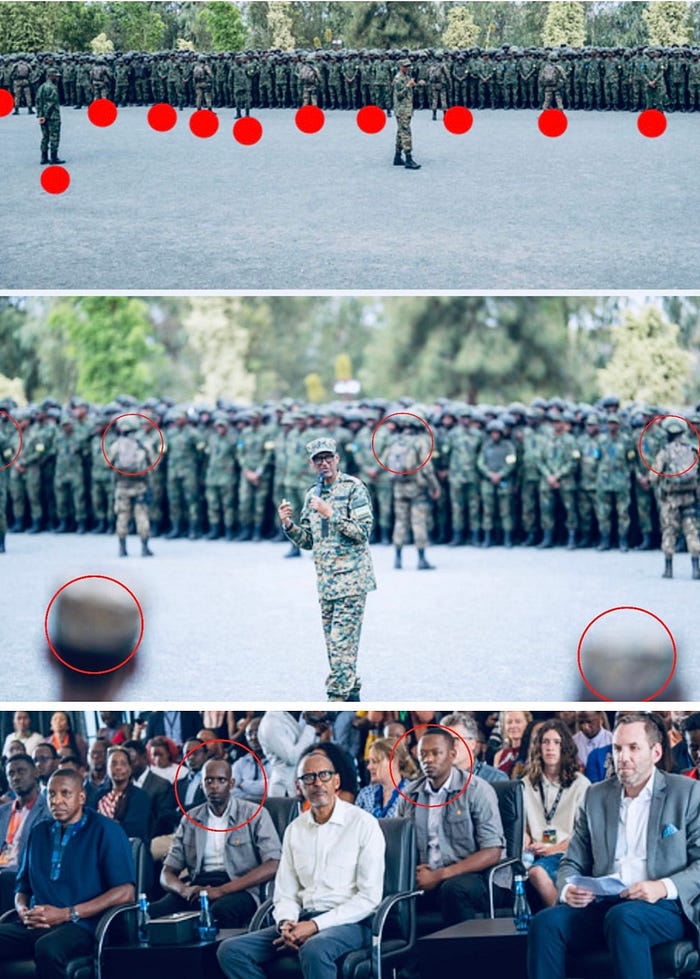

Before I share my views on the exchange between General Paul Kagame and Gallup’s CEO, Jon Clifton, I first make an observation. Kagame’s photographs these days show security overkill. Whether he is addressing his soldiers as a commander in chief, entertaining foreign guests or visiting upcountry rural dwellers, security overkill separates him from his audience. If Rwandans are happily living in the most improved conditions in the world, why security overkill? Looking at Kagame’s security overkill, I am reminded of Sir Winston Churchill’s description of totalitarian rulers and their cowardice:

“You see these dictators up on their pedestals, surrounded by the bayonets of their soldiers…They’re afraid of words and thought…They make frantic efforts to bar our thoughts and words [to create]…a society where men may not speak their mind – where children denounce their parents to the police…Where a businessman or small shopkeeper ruins his competitor by telling tales about his private opinion.”

That is precisely General Paul Kagame’s Rwanda. Like other dictatorial rulers before him, he is trapped inside a paradoxical prison. The more power he accumulates, the more his deep-seated anxiety about his future fate intensifies.

Back to the Kagame-Clifton debate

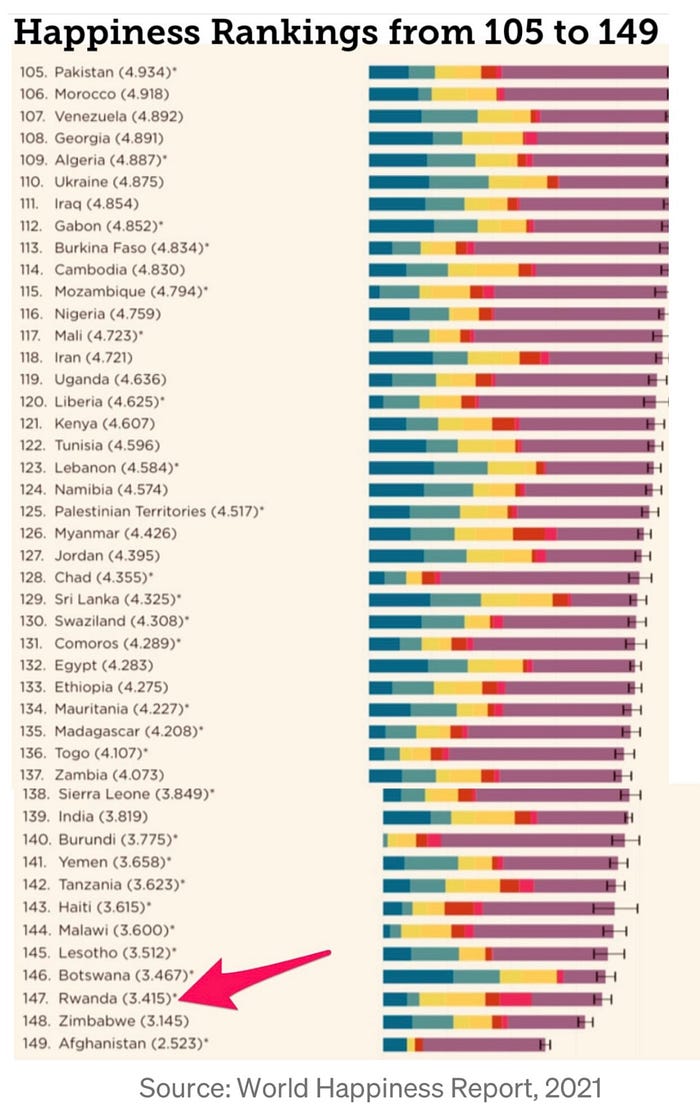

The Kagame-Clifton exchange ensued from the reaction to Gallup’s World Happiness surveys. These surveys consistently rank Rwandans among the wretchedest of the world. In the 2021 survey, for example, only Zimbabweans and Afghans were more miserable than Rwandans.

How does Gallup determine its rankings?

First, Gallup researchers who conduct the surveys ask respondents in the countries surveyed to assess and rate life. A score of 10 is the best possible life; a score of zero is the worst possible condition. Second, the researchers ask respondents to rate their confidence in four governmental institutions: the central government; local police force; the military and the judicial system/courts.

The results from Rwanda are most astonishing due to polar opposite responses from Rwandan respondents. On the one hand, the Rwandan respondents rate their own life situations as miserable. But on the other hand, they rate their confidence in governmental institutions by nearly 100 percent.

As indicated in the table, in the 2019 Gallup survey, citizen confidence in the national government in Rwanda was 99 percent against a global average of 48 percent.

Enter General Kagame

Predictably, General Paul Kagame loved the nearly 100 percent confidence in his government. Praising Gallop, Kagame said:

“If you look at, say, the Gallup polls that have recently been carried out in Rwanda on everything, they show the confidence that people have in the institutions, people have in the government. They all score…better than you can witness in any African country or even other countries outside.”

However, Kagame was later to ferociously dismiss Gallup’s ratings in the following terms:

“[There] is an annual survey known as the World Happiness Report…Rwanda always ranks near the bottom, alongside countries mired in conflict. How could the citizens of the most improved country in the history of the United Nations Human Development report also be amongst the world’s most miserable?”

Enter Jon Clifton

In his book, Blind Spot, The Global Rise of Unhappiness and How Leaders Missed It, Clifton’s Chapter Sixteen titled “A Letter to Rwandan President Paul Kagame” directly responds Kagame’s objections. Broadly, Clifton illustrates how global leaders rely on generic indicators such as the rise in the gross domestic product to the detriment of their populations. He provides examples of countries whose economies are spectacularly growing while citizen wellbeing is declining. Clifton then makes the case that “global leaders should closely follow wellbeing and happiness metrics to better understand how people’s lives are going.” He adds:

“Gallup has produced global statistics for wellbeing and happiness since 2006, and these metrics perfectly complement the objective indicators for human development that leaders already follow so closely…”

Clifton highlights the five elements of wellbeing in which about 2 billion people in different parts of the world including Rwandans are struggling: work, financial, community, physical, and social wellbeing. Clifton explains that Rwandans’ responses to Gallup questions are astonishing. As he puts it:

“Gallup has conducted this study in Rwanda since 2006. Every time, the results are the same. Rwandans rate their lives very poorly every time we interview them, and the country always ends up near the bottom of our international rankings…Gallup asks Rwandans. – and people everywhere. – whether they are confident in their national government, local police, military, and judicial system and courts. And the responses we get to these questions in Rwanda are astonishing. Almost everyone expresses confidence in those institutions.”

Rwanda government own statistics support Clifton – not Kagame

According the 2021 National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda’s Labour Force Survey, published in March 2022, Rwanda’s formal economy employs only 9.6 percent of the country’s workforce. The rest of Rwanda’s workforce comprising 90.4 percent eke out a living in the informal economy. Informal employment is defined by the International Labour Organization (ILO) as work that “in law or in practice, not subject to national labour legislation, income taxation, and social protection.” Vital employment benefits such as pension, advance notice of dismissal, maternity leave, severance pay, paid annual or sick leave do not apply to the informal workplace.

In Rwanda, a country led by Kagame for three decades shy one year, the informal economy is collosal and all-encompassing. The cited 2021 Rwanda’s Labour Force Survey reveals the following:

“There were in total 2,981,209 persons with informal employment at main job constituting almost 90.4 percent of total emplovment.”

Shockingly, even Rwanda’s formal economy employs informal workers. As described by the 2021 Rwanda’s Labour Force Survey, “a significant result was the presence of some 131,529 persons with informal jobs in the formal sector.” Meanwhile, according to the Rwandan Development Board’s 2022Rwanda Annual State of Skills, Supply and Demand, Rwanda’s private sector remains microscopic. “Over 90% of all businesses are nascent, informal, and concentrated in the non-tradable sectors.”

The structure of the Rwandan workforce by education levels is shown in the following table.

The workforce with no education is 46.9 percent versus 32.1 percent who completed primary; 6.1 percent lower secondary; 8.5 percent upper secondary and 6.4 percent university. In other words, the combined workforce without education and the workforce with primary school education is 79 percent. Now, compare the lives of the 90.4 percent of Rwandan workforce still trapped in the informal economy to how the government describes its “tremendous” economic achievements under Kagame’s totalitarian rule of the past 29 years:

“Rwanda’s economy has tremendously recovered over the last two decades. Rwanda’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has risen from $752 million in 1994 to $9.5 billion in 2018, and the GDP per capita has grown from $125.5 to $787 during the same period. The country registered an average GDP growth of around 8 percent per year over the last two decades, with a double-digit growth recorded in the last two quarters of 2019 (12% growth in the 2nd quarter, and 11.9% in the 3rd quarter)…Inflation has fallen from 101% in 1995 to 1.1% in 2018. Collected domestic taxes increased 20 times while the national budget increased 14 times over the last 20 years.”

And that is precisely Clifton’s point on countries with impressive economic growth rates side by side with gross citizen misery. The growth statistics cited by the Kagame government clash with the 90.4 percent of 14 million Rwandans still locked out of the country’s formal economy.

Why do Rwandans express a near total confidence in governmental institutions despite their wretched conditions?

Kagame hinted at the answer to this question when he cited “cultural reasons” to explain how and why Rwandans respond to Gallup survey questions in unique ways. For the term “cultural reasons” in this context, read survival instincts. When your homeland is ruled by iron-fisted rulers who violently grabbed power since 1896, your self-preservation takes over. The moment you start asking questions or expressing an independent opinion, you are an endangered species. Keeping one’s head down, asking no questions and challenging no one is now a deeply ingrained Rwandan culture, and an insurance policy for self-preservation. This is what explains why, for example, only 1.68 percent of Rwandans voted against the 2015 constitutional referendum that extended Kagame’s rule to 2034 with a voter turnout of 100 percent.