By David Himbara

Paul Rusesabagina’s autobiography An Ordinary Man, is no ordinary book. Besides telling the story of how Rusesabagina saved lives during the 1994 genocide, An Ordinary Man challenges Rwandans to step forward and rescue their country from ethnic-based dictatorships. As Rusesabagina explains, in Rwanda power passes from one violent ethnic-based regime onto the next “with neither side learning anything from the ashes and bodies.” He calls upon Rwandans untainted by ethnic ideologies to engage in a forthright conversation on a shared purpose which, in his own words “never happened, not once in Rwandan history.” Rusesabagina’s portrayal of all post-independence regimes in Rwanda as manifestations of “corrupt ethnic visions” is exemplary among Rwandan activists who determinedly see no wrong in their “own” ethnic dictatorship. Rusesabagina’s abduction by General Paul Kagame’s regime has a silver lining – renewed interest and enthusiasm for the perceptiveness embedded in the book, An Ordinary Man.

The main story in Paul Rusesabagina’s An Ordinary Man is his role in saving lives during the 1994 genocide

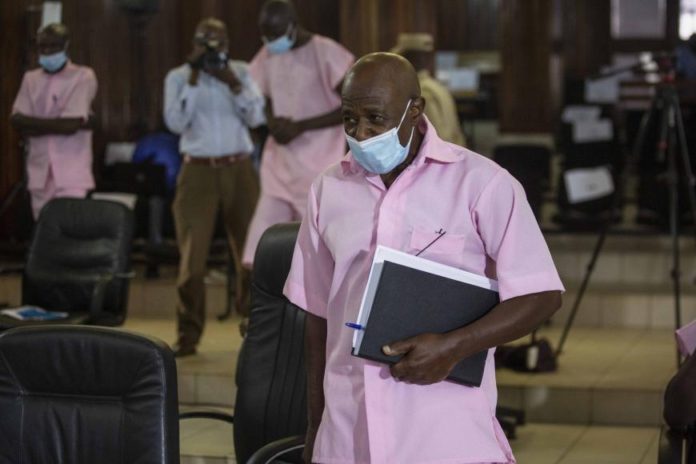

Rwanda’s iron-fisted ruler, General Paul Kagame, abducted Paul Rusesabagina from Dubai in September 2020 in an act that has put a spotlight on Rwandan unhinged politics. This episode renewed interest and enthusiasm in Rusesabagina’s autobiography, An Ordinary Man. The main story in An Ordinary Man, is widely known, thanks in large part to the acclaimed film, Hotel Rwanda, based on this work. The book describes Rusesabagina’s experience during the one hundred days of mass murder in 1994, when all hell broke loose, forcing Rwandans into a terrible choice – kill or be killed. Neighbours who had lived side by side in relative peace suddenly hacked each other with machetes over a supposed difference in ethnicity.

The context of An Ordinary Man is the period leading to the 1994 genocide in which the government of the Hutu dictator, General Juvénal Habyarimana, through insidious radio broadcasts, spread hate propaganda against the Tutsi. The radio broadcasters would say things to stir up the Hutu to violence against the Tutsi, who formerly made up the ruling elite in Rwanda and are supposedly a taller group of people with slenderer noses than the Hutu. The broadcasters referred to the height of the Tutsi, dehumanizing and killing them by comparing them to tall trees. “Do your work,” the announcers would say. “Clean your neighborhood of brush. Cut the tall trees.”

The distinctive feature of An Ordinary Man is Rusesabagina’s description of how he rose to the occasion by providing sanctuary to Rwandans who were inches away from death. He turned the hotel Mille Collines where he worked as a manager into a refuge for more than 1,200 Tutsi and moderate Hutu refugees, while fending off their would-be killers. He did what he felt was morally right, even when faced with the possibility of his own death because he wouldn’t kill his compatriots. Through negotiation, favor, flattery and deception, Rusesabagina managed to keep his “guests” alive despite the homicidal gangs just outside the fences of hotel Mille Collines.

Rusesabagina kept a ledger of government officials who owed him favors and called them at different crucial points, keeping the hotel from being stormed and people from being slaughtered. He offered the generals or other military bosses money, alcohol, or whatever would work to keep the people inside the hotel alive for another day. This recalls individuals who rescued Jews from the Holocaust conducted by Nazi Germany during World War II. Think of Oskar Schindler, a German industrialist who is credited with saving the lives of 1,200 Jews during the Holocaust by employing them in his factories.

Rusesabagina’s second achievement in An Ordinary Man is not widely acknowledged

Rusesabagina An Ordinary Man has a second and less acknowledged purpose. An Ordinary Man is a rallying cry for the rejection of tribal politics by Hutu and Tutsi because, as Rusesabagina explains, both ethnic groups pay a heavy price whenever their respective elites are not in power. This book does not suffer from what I call “my dictator is better than yours” syndrome. This widespread complex produces one-sided interpretation of Rwandan history that is sympathetic to the one’s own ethnic group while ignoring the victimization of other ethnic group. The Tutsi suffering from this syndrome are largely silent on the Tutsi feudal rule that relegated the Hutu into labouring serfs in precolonial and colonial Rwanda. And while the Tutsi suffering from the syndrome write about the violence at the hands of the post-independence Hutu regimes, the Tutsi writers remain largely silent on the Kagame regime’s crimes against the Hutu population in Rwanda and DRC.

The Hutu suffering from the ethnic syndrome paint an entirely different picture of Rwanda’s social history. They emphasize the exploitation of the Hutu masses at the hands of the Tutsi in precolonial and colonial phases. But they rarely acknowledge the periodic violence unleashed against the Tutsi from 1959 onwards. The Hutu suffering from ethnic syndrome also have difficulty in acknowledging how post-independence Hutu regimes locked thousands of Tutsi out of Rwanda into perpetual refugees. This shortsightedness guaranteed a violent return by the refugees 30 years after they were exiled.

Rusesabagina’s An Ordinary Man does not suffer from the syndrome of “my dictator is better is yours.” Far from it. To Rusesabagina, every regime failed the people of Rwanda from the days of the dynastic Tutsi kingdom led by under the mwami or King. In this system known as ubuhake, those who didn’t have cattle, and by definition, mostly Hutu, were forced to supply labour to the Tutsi. In Rusesabagina’s telling, when the Tutsi aristocratic rule was overthrown in 1959 by the Party for Hutu Emancipation (Parti du Mouvement de l’Emancipation du Peuple Hutu) under the leadership of Grégoire Kayibanda, Rwanda’s problems did not end. On the contrary, Rwandan politics became a violent affair. This Rusesabagina’s own description of what followed:

“Tens of thousands of persecuted Tutsis fled the country to the safety of Uganda and other neighbouring nations. [O]ur new government of President Grégoire Kayibanda [began] to wrap itself in the Hutu Revolution and began a purge of the Tutsis who remained inside Rwanda. There is no greater gift to an insecure leader that quite matches a vague ‘enemy’ who can be used to whip up fear and hatred among the population. And this just what the new regime did. The persecution was made easier because Rwanda is a meticulously organized country…It was the duty of every good and patriotic Hutu to join ‘public safety committees’ to periodically help ‘clear the brush.’ Everybody understood this to mean slaughtering Tutsi peasants…In 1963 thousands Tutsi were chopped apart…These countryside massacres continued off and on throughout the decade…”

The next Hutu dictator was no better than Kayibanda after the father of the Hutu revolution was overthrown, his entire government cabinet members massacred, while Kayibanda and his wife were starved to death. Here is Rusesabagina’s description of the next Hutu regime led by Juvénal Habyarimana:

“The rift in my country is not just between the Hutus and Tutsis. There is also a rivalry between Hutus from the northern part of the country and Hutus from everywhere else. After Juvénal Habyarimana came to power in 1973, a tight circle of his friends from the north part of the country, especially people with family ties in towns like Gisenyi and Ruhengeri, managed to dominate all key cabinet posts and high-paying civil service jobs.”

This is how Rusesabagina describes the preparation of the 1994 genocide by the Habyarimana’s regime:

“The formation of the youth militias was obvious. It was hard to miss those roving bands of young men wearing colourful neckerchiefs, blowing whistles, singing patriotic songs, and screaming insults against the Tutsis, their sympathizers and members of the opposition…They were known as Interahamwe, which means either “those who stand together” or “those who attack together’ depending on who is doing the translating. Habyarimana’s government formed them into ‘self-defence militias” that operated as a parallel to the regular Rwandan army and were also used to threaten the president’s political enemies. They were also a tool for building popular support for the ruling regime under the all-embracing cloak of Hutu power.”

Rusesabagina makes the following statements about post independence Rwanda and how the culture of impunity took root from 1959 onwards:

“I am convinced that one of the strongest engines of the Rwandan genocide was the culture of impunity that was allowed to flourish after the revolution against the colonists in 1959. Rwandans killed their neighbours just to take their houses, people killed people for their banana trees, people leaped over the counters of abandoned general stores and started selling the merchandise as if they were the rightful owners. It was a huge mistake for our government to let this blatant larceny to go unanswered. Even today there are people living in houses that don’t belong to them and selling merchandise they never bought. This is what I call impunity.”

What about the Tutsi regime of Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) which captured power in 1994 led by the same Kagame sent into exile as a child in 1959? This is Rusesabagina’s description of the Kagame regime:

“Rwanda is a country that has still never known democracy. The current president, Paul Kagame, was the general of the Rwandan Patriotic Front army that toppled the génocidaire regime and ended the slaughter, and for this he deserves credit. But he has exhibited many characteristics of the classic African strongman ever since taking power. In 2003 he was re-elected with 95 percent of the vote. There is nobody in the world that can call results like that a ‘free election’ and keep a straight face. Moreover, the popular image persists that Rwanda is today a nation governed by and for the benefit of a small group of elite Tutsis…Those few Hutus who have been elevated to high-ranking posts are usually empty suits without any real authority of their own. They are known locally as Hutus de service, or ‘Hutus’ for hire. So there is no real sharing of power. What exists now in Rwanda is a new version of the Akazu, or the ‘little house’ of corrupt businessmen who have long surrounded the president. The same kind of impunity that festered after the 1959 revolution is happening again, only with a different race-based elite in power. We have changed the dancers but the music remains the same.”

As is evident from his descriptions of post independence regimes, Rusesabagina is fair and impartial in his judgment, concluding that the regimes were pretty much the same, the Hutu and Tutsi labels notwithstanding. This must change, writes Rusesabagina, who is an optimist on the future Rwanda. According to him, the missing element is a forthright conversation among the people of Rwanda, which never happened, but is overdue as Rusesabagina explains:

“What my country needs most of all is to sit together around the table and talk. Perhaps we will not talk as best as friends, not yet, but at least as people with a common history who respect each other. That discussion never happened, not once in the Rwandan history. The dictates of the mwami were followed by the plunder of the country by Belgians and then the corrupt ethnic visions of Habyarimana, with the balance of power always bouncing back and forth between the races, and neither side learning anything from the ashes and the bodies. We never talk about it; we just steal what we can whenever our turn comes around.”

Imprisonment of Rusesabagina will not extinguish the message of An Ordinary Man

In conclusion, Rusesabagina’s An Ordinary Man, is an extraordinary book that must be read by all Rwandans who envision a democratic Rwanda. An Ordinary Man is an optimistic writing that challenges Rwandans to embrace the idea that their country is not preordained to remain a war-theatre in which power-hungry ethnic cliques take turns in murdering sections of the Rwandan population. Kagame’s imprisonment of Rusesabagina does not incarcerate the message in An Ordinary Man. A conversation among Rwandans on abandoning winner-take-all ethnic rivalries that perpetuate violence is a powerful idea that no strongman can extinguish.