John J Stremlau, University of the Witwatersrand

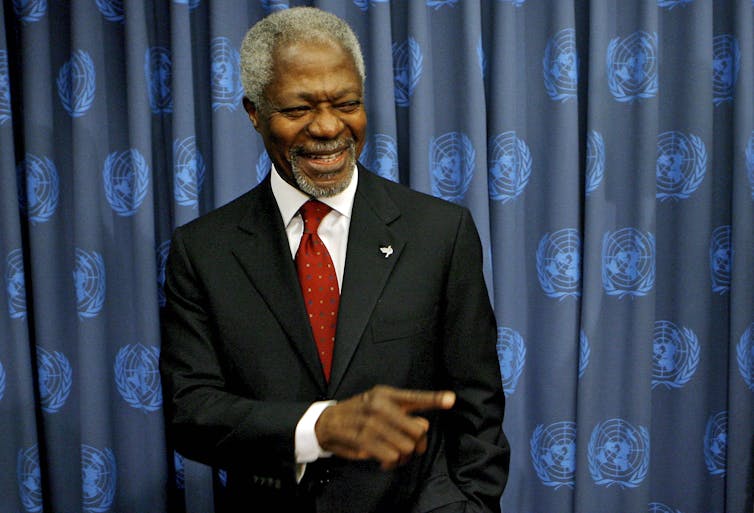

Kofi Annan served as United Nations Secretary-General during a pivotal decade in modern world history – from 1997 to 2006. I would argue that his most important legacy was to focus the UN more on preventing and resolving deadly conflict within its sovereign members, while still trying to maintain peace and security among them.

How he developed and pursued ways and means to do this began much earlier in his UN career and persisted until his untimely death last week.

The UN was created in 1945 by 51 sovereign states and empires that had just survived two of the worst wars in history. With the winding down of empires, UN membership grew to nearly 200 countries. By the late 1990s most countries were at peace internationally. And despite their continuing ideological and other differences, they have, ever since, avoided another world war.

But domestic peace was to prove more illusive. The UN lacked the norms, institutional capacity and political resolve, to prevent and resolve deadly conflicts within states, while maintaining peace among them. Although Africa accounted for nearly a third of the UN’s members, it was also the world’s poorest and most conflict-ridden region. And it lacked the means to effect major reforms in the world body’s post-World War II hierarchy, structures and procedures.

Annan knew the UN system and its strengths and limitations better than anyone. He had spent 35 years working on the problems of refugees, management and finance, and peacekeeping having joined it in 1962 as a young budget officer in the World Health Organisation.

He had also felt the sting of governments and public opinion that regarded the UN as a necessary last resort, when all other options have failed, due to lack of national or regional capacity, resources or political will. This was most evident when it came to complex emergencies in Africa.

His message for Africa

Six months after becoming Secretary-General, Annan chose to address the 1997 summit in Harare of leaders of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in a way that none of his predecessors had done.

His central point was that Africa’s peace and development required Africa’s leaders to hold one another more accountable to how they managed their domestic affairs. This was particularly true when it came to the protection of human rights and democracy.

In language uncharacteristically passionate for such occasions he declared:

I am aware of the fact that some view this concern a luxury of rich countries for which Africa is not ready … I find these thoughts truly demeaning…. Do not African mothers weep when their sons or daughters are killed or maimed by agents of repressive rule? Are not African fathers saddened when their children are unjustly jailed or toured? Is not Africa as a whole impoverished with even one of its brilliant voices is silenced?

He concluded by emphasising that “human rights are African rights”, noting that “Africa needs external assistance, and Africa deserves it, but in the final analysis, what stands between us and the future is ourselves”.

Four years later, the OAU was replaced by the African Union (AU). What was notable was the unprecedented inclusion of a provision for collective intervention to protect any group of Africans facing local threats of mass violence or genocide.

Less extreme, but more generally applicable, was the principle of non-indifference in each other’s internal affairs. This is most evident in its auxiliary African Charter for Democracy, Elections and Governance which was unanimously endorsed in 2007 and finally ratified in 2012.

As a result, all African governments are now obligated to hold regular periodic national elections. They are also obliged to invite the AU to send teams of pan-African observers to monitor and judge whether they are a credible reflection of the popular will.

Annan would not claim credit for these developments. But, his efforts were surely prescient and gave political impetus and legitimacy to the hard diplomatic work of South Africa’s President Thabo Mbeki, President Olusegun Obasanjo of Nigeria, and other advocates of a more capable regional organisation and sub-regional organisations.

Embracing civil society

Also notable in his 1997 address to the OAU was his call for civil society to play its part. This reflected what was to become one of his major innovations as UN Secretary-General – his openness and willingness to reach out, listen too, cooperate with and occasionally adopt policies advocated by civil society groups.

I personally know of at least four examples. All were Africa-related but also global in nature and very much to his credit as we honour his legacy.

- During the 1980s he participated in a series of efforts by the International Peace Academy, an NGO established to help train and better inform and prepare for expected UN peacekeeping operations, mostly in Africa. This capacity should have been institutionalised in the UN, but was thwarted by the US and Soviet Union. Both feared that the other might somehow gain a Cold War advantage. The NGO never fully succeeded and would have probably failed without Annan’s frequent personal and sustained engagement.

- As Secretary-General he made cooperation with the independent Carnegie Commission on Preventing Deadly Conflicts his personal priority. He attended commission meetings and encouraged the involvement of key offices across the secretariat. As a member of the commission staff, I appreciated how extensively he used policy relevant scholarship by teams of academics on a range of conflict prevention topics. His aim was to build support within and beyond the UN for more comprehensive efforts to prevent complex emergencies within states.

- After leaving office he continued to promote, and often lead, civil society efforts to help the UN and the world, beginning in Africa. In 2006 he became the founding chair of Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). AGRA aims to increase the incomes and improve the food security for 30 million farming households in 11 African countries by 2021.

- In his home country Ghana, I watched with admiration how his Foundation sponsored presidential debates in which candidates publicly pledged to support the decision of the national electoral commission. And when the opposition won by less than .005% of the votes in the 2008 election, their pledge held.

- And, best known, has been his chairmanship of the Elders, a group of world leaders committed to advancing peace, especially in Africa, and founded by Nelson Mandela.

The importance of persistence

I last met with Annan several years ago when he was on Elders’ business and I asked what he thought of Robert Mugabe holding on to power more than a decade after his pro-democracy appeal to the OAU Summit in Harare.

He told me that near the end of his UN term he had visited Mugabe and inquired whether he might consider bidding farewell to his people after decades of service. He said, Mugabe asked in reply: “Why? My people aren’t going anywhere.”

Annan noted that this response was both a sign of the limits of diplomacy, as well as the reason never to stop trying.

________________________________________________________

John J Stremlau, Visiting Professor of International Relations, University of the Witwatersrand

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.