“Imagine how much happier we would be, how much freer to be our true individual selves, if we didn’t have the weight of gender expectations. I used to look up to my grandmother who was a brilliant, brilliant woman, and wonder how she would have been if she had the same opportunities as men when she was growing up. Now today, there are many more opportunities for women than there were during my grandmother’s time because of changes in policy, changes in law, all of which are very important. But what matters even more is our attitude, our mindset, what we believe and what we value about gender. What if in raising children we focus on ability instead of gender? What if in raising children we focus on interest instead of gender?”

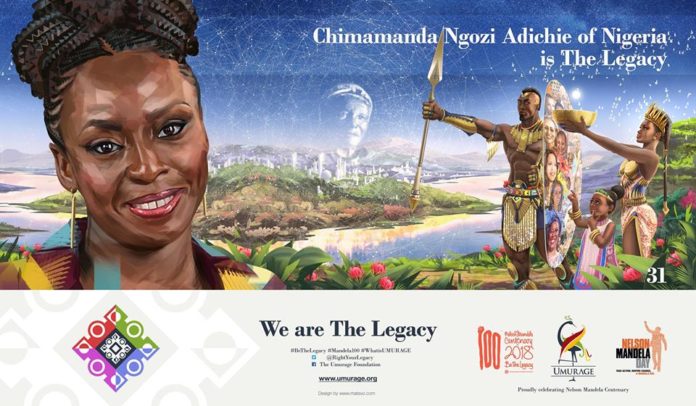

Today, I am starting my article with the words of the inspirational Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Chimamanda, an Igbo name meaning “my God will never fail”, was born in September 1977 in Enugu, a city of about 700,000 inhabitants in south-eastern Nigeria.

She was the fifth of the six children of Grace Ifeoma and James Adichie.

Chimamanda started reading and writing when she was very young, practically at the age where others are still learning how to speak. The only books she could get in those days were children books by British and American authors, and without realising it, the little Nigerian girl she formed the idea in her mind that only foreigners could write books or be the subjects of print stories. When she started writing, she created worlds where all characters where white, lived in the northern hemisphere – where she had never set foot – and their lives where rhythmed by snows she had never seen, and suns that disappeared and reappeared at different times of the year, unlike her own environment where the sun seemed to be permanently fixed in the sky.

At that age, she did not realise how her young impressionable mind had been influenced by the books she read, books where someone who looked like her had no place.

When she was 10, her family moved to the Nigerian university town of Nsukka, where her father was to lecture at the University of Nigeria. Her mother was a pioneer in her own right: she was the first woman to hold the post of the university’s registrar.

Coincidently, the Adichie family moved in a house once occupied by the author of ‘Things fall apart’, the late Chinua Achebe. It’s in Nsukka that she discovered Chinua Achebe’s writings and books by other African authors such as Camara Laye, author of ‘The African Child’, that she realised that Africans too could write books, with African characters in an African setting!

It was like a real rebirth!

“Because of writers like Chinua Achebe and Camara Laye, I went through a mental shift in my perception of literature. I realised that people like me, girls with skin the colour of chocolate, whose kinky hair could not form pony tails, could also exist in literature. What the discovery of African did for me, it saved me from having a single story of what books are.”

That awakening changed her life and altered her idea of herself and her identity.

When she completed her secondary education, the young lady enrolled at the University of Nigeria in Nsukka, to study Medicine. It wasn’t her dream, but her parents dream for her. They had this set idea that their children would have professions that would allow them to make a proper living. Chimamanda older sister was a doctor, another one was a pharmacist and her brother was an engineer.

After a while trying to live up to their expectations of her, Chimamanda decided to open-up to her parents and tell them that she had decided to drop-out of medical school and to pursue her own dream: to become a writer. To her surprise her parents were supportive of her choice despite the fact many would have killed to have the chance to enter this ultra-competitive field.

She often made fun of her parents releasing her of her obligation to follow her siblings’ footsteps.

“My parents already had sensible children who would be able to make an actual living, and I think they felt comfortable sacrificing their one strange child.”

They probably expected it. During the year and a half that their daughter studied at Nsukka, she had made a name for herself as the editor of ‘The Compass’, a magazine run by the university’s Catholic medical students.

In 1997, 19 years old Chimamanda left her homeland to go and study in the United States where one of her sisters lived. For the first time of her life, she was about to live her own life, not a life that had been designed for her by her family and traditions.

She had opted to study communication and political science at the Eastern Connecticut State University.

A year later, at age 20, Chimamanda published a play called ‘For Love of Biafra’, a play about the war between Nigeria and its secessionist Biafra republic, that plagued her country in the late 1960s. Chimamanda the militant dreamer/writer was born!

After obtaining her Bachelor’s degree from Connecticut in 2001, Chimamanda enrolled in a Master’s Degree program in creative writing at the prestigious Johns Hopkins University. While a student at the Baltimore based university, Chimamanda pursued her love of writing, publishing short stories in the school’s Magazine, before publishing her first novel, ‘Purple Hibiscus’ at age 25.

She had been encouraged by Muhtar Bakare, a visionary man who had left the lucrative profession of banking to follow his dream of becoming a publisher. One of the things she liked about Muhtar Bakare is that he strongly believed that anyone who can read would read if you made books more affordable and accessible.

‘Purple Hibiscus’, a coming-of-age story of Kambili, a 15-year-old whose family is wealthy and well respected but who is terrorized by her fanatically religious father, was an instant literary success, winning the 2005 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best First Book!

The author recalls how she was humbled by an encounter she had with a woman who worked as a messenger in a TV station where she was to do an interview and approached the young lady to tell her that she had read the book.

“Here was a woman, part of the ordinary masses of Nigerians who were not supposed to be readers. She had not only read the book, she had taken ownership of it and felt justified to tell me what to write in the sequel.”

In 2006, Chimamanda published her second novel, Half of a Yellow Sun. Though a fiction, ‘Half a Yellow Sun’ was primarily based on the experiences of her own parents during the Nigeria-Biafra war.

‘Half of a Yellow Sun’ also became an international best seller and was awarded several awards, including the Orange Broadband Prize for Fiction, the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, the PEN ‘Beyond Margins’ Award and the Orange Broadband Prize for Fiction.

The young lady was on a roll: in 2009, while completing a second Master’s degree at Yale – this time in African History – she released ‘The Thing Around Your Neck’, a critically acclaimed collection of short stories.

Though her writing had undeniably established herself as an exceptionally gifted writer, the name Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie was going to become an international household name across all media in July 2009, when she was invited to speak at the international TED Global 2009, held in Oxford, UK.

In line with the conference’s theme, “The Substance of Things Not Seen”, the young African novelist chose to speak of ‘The Danger of a Single ‘, a subject that resonated with everyone in the world who had ever felt misrepresented or completely erased of the mainstream story.

In her poised, elegant and deliberate manner that we are so fond of – I know I am – the author recalled her early childhood and her journey to follow her dream, using her own life experiences to alert us on the dangers of building the wrong ideas about people just because you because you learnt ‘all there is to know about them’ from one sole source.

I could particularly relate to her recollection of her first days in America, when she was 19. It hadn’t taken long for young Chimamanda to realise that people had a lot of pre-conceived ideas about African and Africans, and they were surprised whenever they realised, she did not fit those stereotypes.

“My American roommate was shocked by me. She asked where I had learned to speak English so well and was confused when I told her that Nigeria happened to have English as its official language. She asked if she could listen to what she called my ‘tribal music’ and was consequently very disappointed when I produced my tape of Mariah Carey”, she shared, bringing her audience to laugh to tears.

“What stroke me was this: she had felt sorry for me even before she saw me. Her default position towards me, as an African, was a kind of patronising well-meaning pity. My roommate had a single story of Africa, a single story of catastrophy. In this single story, there was no possibility of Africans being similar to her in any way, no possibility of feelings more complex than pity, no possibility of connection as human equals.”

She went on to ask if people like her roommate would have had such a narrow idea of Africa if they had bothered to know the multiple sources of stories of extraordinary Africans who were breaking away from the idea that the world had of what an African was or should have been.

The author ended her address with this powerful statement: “Stories matter. Many stories matter. Stories have been used to dispossess and to malign, but stories can also be used to empower and to humanize. Stories can break the dignity of a people, but stories can also repair that broken dignity. When we reject the singe story, when we realise that there was never a single story about any place, we regain a kind of paradise.”

The audience gave her a standing ovation. Chimamanda, the dreamer, had become the voice of the voiceless.

To this date, “The Danger of a Single Story” has been viewed more than 17 million and 500 times and the transcript of her 19minute talk was translated in 49 languages!

Another major milestone in Chimamanda life came in 2013, when her book ‘Half a Yellow Sun’ was turned into a Hollywood movie featuring Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor and Anika Noni Rose. The joy of the moment was overshadowed by the fact that Nigeria’s film board had first banned the movie in Africa’s largest economy, suggesting it could ignite ethnic tensions in the country, before finally allowing it to be shown.

In 2012, some three years after the famous viral speech, Chimamanda came back to TED with another thought-provoking topic: “We should all be feminists”.

The gifted orator started by telling the audience of a friend she had when she was younger and who had since passed away. Okoloma, whom she considered as a big brother, used to call her a ‘feminist’ but in an accusatory way that made it clear it was no compliment:

“I could tell from his tone, the same tone that you would use to say something like, ‘You’re a supporter of terrorism.’ I did not know exactly what this word “feminist” meant, and I did not want Okoloma to know that I did not know. So, I brushed it aside, and I continued to argue. And the first thing I planned to do when I got home was to look up the word “feminist” in the dictionary.”

She told of another time later in her life when she was promoting one of her books and received an unsolicited advice from a compatriot:

“You should never call yourself a feminist because feminists are women who are unhappy because they cannot find husbands.”

She also gave examples of times in her life where she was seen and treated as less than men, sometimes in such subtle ways that people around her did not necessarily see, often because they were blinded by their cultural bias on what a man or a woman should be, the positions they should or shouldn’t occupy.

“Each time they ignore me, I feel invisible. I feel upset. I want to tell them that I am just as human as the man, that I’m just as worthy of acknowledgment. These are little things, but sometimes it’s the little things that sting the most.”

She continues to say: “I am angry. Gender as it functions today is a grave injustice. We should all be angry. Anger has a long history of bringing about positive change; but, in addition to being angry, I’m also hopeful. Because I believe deeply in the ability of human beings to make and remake themselves for the better.”

The talk was enlightening, and a most powerful lecture aimed at changing how we view man and woman and how we raise boy and girl in such a way we set them up to perpetuate the biases in our society.

“Gender matters everywhere in the world, but I want to focus on Nigeria and on Africa in general, because it is where I know, and because it is where my heart is. And I would like today to ask that we begin to dream about and plan for a different world, a fairer world, a world of happier men and happier women who are truer to themselves. And this is how to start: we must raise our daughters differently. We must also raise our sons differently. We do a great disservice to boys on how we raise them; we stifle the humanity of boys. We define masculinity in a very narrow way, masculinity becomes this hard, small cage and we put boys inside the cage. We teach boys to be afraid of fear. We teach boys to be afraid of weakness, of vulnerability. We teach them to mask their true selves, because they have to be, in Nigerian speak, ‘hard man’!”

“And then we do a much greater disservice to girls because we raise them to cater to the fragile egos of men. We teach girls to shrink themselves, to make themselves smaller, we say to girls, “You can have ambition, but not too much. You should aim to be successful, but not too successful, otherwise you would threaten the man.”

Indeed, we must change!

Following the success of her second TED talk, Chimamanda published in 2014 an essay “We Should All Be Feminists”. In 2017, the prolific author published “Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions”, a powerful new statement about feminism today — written as a letter to a friend.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has a two years old daughter with husband Ivara Esege, a medical doctor. She spends her time between the US and Nigeria, where she co-runs Farafina Trust, a non-profit organization established to promote reading, writing, a culture of social introspection and engagement with society through the literary arts.

In 2016, Chimamanda received from her alma mater Johns Hopkins University an honorary Doctorate of Humane letters, and in 2017, honorary Doctorate degree of Humane letters from Haverford College and The University of Edinburgh. In 2018, she received a Doctorate Honoris causa of Humane Letters from Amherst College.

Let’s celebrate International Women’s Day 2019 with our celebrated sister Chimamanda by vowing to all be feminists.

Right Your Legacy, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie!

Contributor