Jonathan Sears, University of Winnipeg

How credible were the 2018 presidential elections in Mali? Going by the allegations of stuffed ballot boxes, theft of election materials, threats and attacks against election officials, arson at polling stations, vote-selling, and buying, it could be argued that the poll wasn’t credible at all.

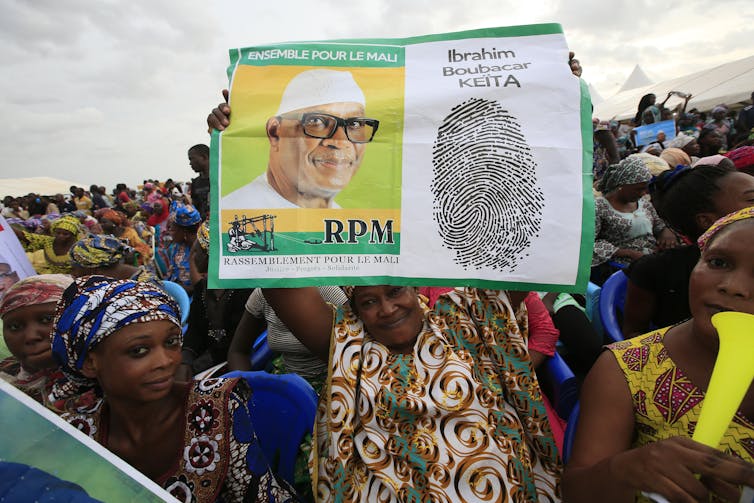

As many had predicted, the incumbent, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, won in the second round.

That the African Union and the European Union called the vote credible and transparent came as something of a surprise given that violence and fear also curtailed voter turnout.

But the observers stopped short of a full endorsement. They used nuanced language, declaring the poll “credible if flawed”. This points to the challenges faced in holding elections under complex and troubling conditions.

Unfortunately, this picture also deepens the sense that national and international interests may outweigh scrupulous oversight of elections. It also suggests that that those who engaged in electoral fraud and violence aren’t likely to be properly investigated and prosecuted.

There’s also a larger issue. By rubber stamping flawed elections, international observers significantly bolster the legitimacy of the Malian president in the face of significant, if fragmented, political opposition.

This is a very important period in Malian political history. Although opposition leader Soumaila Cissé has been unable to unite Mali’s opposition, the opposition still expresses Malians’ rejection of status quo politics. Keita needed a runoff vote to win – unprecedented for an incumbent president in Mali.

Legislative elections due in November and December could be a turning point for Mali as the people mobilise around good governance, development, and the national security gaps that must be acknowledged and addressed by their leaders.

At stake is how well the opposition candidates can mobilise voters to put Keita on notice. Alternatively, the reelected president could enjoy a strong showing of his political supporters, which would see his legitimacy reinforced, and status quo politics affirmed.

Putting things in context

What then can Malians expect from Keïta’s second term? To answer this question it’s useful to take stock. His first term, which ran from 2013 to 2018, was uninspiring. Rather than stem the political decline under his predecessor Amadou Toumani Touré, in office from 2002 to 2012, he maintained it.

Then came Mali’s 2012 multidimensional crisis. The crisis was sparked by a Tuareg-led insurgency which led to a coup d’état. This allowed jihadist violence to expand, exposing the weakness of the Malian state especially in Mali’s northern zones. The democratic gains that the country had achieved since the 1990s were shown to be impermanent and reversible.

Since then, not even interventions by the French, the United Nations, the G5 Sahel (a force that pools troops from Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger), and the EU have been able to prevent the multiplication of armed groups that are now increasingly active in central Mali.

Six years after the crisis key questions remain largely unanswered. Mali has yet to reconcile itself as a cohesive, and stable unit.

Can Keita place the country on the path to socio-economic and political stability? That remains to be seen. But even if he works very diligently and effectively, it will certainly take more than a five-year term.

The conditions of his reelection will certainly inform the political context of his legacy. Opposition leader Cissé persists in rejecting the election results. He cites extensive and systematic fraud. This is significant because Mali’s opposition challengers have traditionally challenges, but ultimately respected election results when they have lost.

This time around, Cissé’s complaints are not simply those of a sore loser. His intransigence signals the latest crisis in Mali’s democratic consolidation. It suggests that cracks are widening in the country’s longstanding political discourse of unity and reconciliation.

The current and future state of Mali’s democracy is once again in question. Is it entering a deepening crisis? Is Cissé’s strong reaction to his loss a sign of frustration that the establishment opposition is basically unable to represent credible political alternatives for Mali’s future?

These are questions that can only be answered going forward. Certainly, not all who are opposed to status quo politics in Mali have lost their energy, and neither have they been co-opted by the Keita administration.

Looking beyond the status quo

Keita’s reelection has done little to dispel Malians’ chronic mistrust of political institutions, processes and actors. To regain the trust of the electorate, the Keita administration must address allegations of electoral fraud, as well as corruption, injustice, and violence.

Human rights violations, corruption, and nepotism are at the core of many Malians’ mistrust. This compromises the government’s legitimacy in communities across the country. Indeed, the chance to repair the social contract between the people and their government was one of the biggest missed opportunities of Keita’s 2013—2018 term.

This is why the stakes are so high for the national legislative elections coming up in November and December 2018. Malians want and deserve better leadership. These elections will give them a better platform to communicate their continued dissatisfaction with the status quo.

Keita’s inauguration has already kick-started mobilisation for positions and support. And certainly, the parties and candidates that align with the president will enjoy advantages stemming from resources, endorsements, and support of his Rally for Mali party and from his Prime Minister Soumeylou Boubèye Maïga. Opposition politicians will be tempted to join the Convention of the Presidential Majority, and seek the advantages and influence of supporting rather than opposing the reelected president. Rewards will be sought. Promises will be made.

But there are no guarantees.

A wide range of issues still need to be taken into account ahead of the parliamentary elections. Not least is the possibility, if remote, of a reconstituted opposition able to communicate Malians’ deep desire for change to their reelected president and his administration.

These desires are that Keita works to resolve the multidimensional problems of corruption and impunity and addresses the persistent issues of poverty, precarious livelihoods, and exclusion. Keita’s second mandate must seek to redeem the first.

_____________________________________________________![]()

Jonathan Sears, Assistant Professor, International Development Studies, Menno Simons College, University of Winnipeg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.