On January 20, 1993, a few hundred distinguished personalities and an impressive crowd coming from the four corners of the country gathered in Washington DC for a historic event. Amongst them, a black woman unknown to the general public, quietly waiting for the protocol to call upon her.

When the time came, she stood up with grace, walked over to the man who was honoured that day, bowed respectfully before taking position before the stand. She was wrapped in a dark-coloured cardigan with gold buttons, a red scarlet ribbon pinned on her chest, a symbol of her solidarity with the victims of AIDS.

Despite the harsh cold of this Eastern American winter morning, she did not wear a hat as did many women in the audience. It was as if she had decided to showcase her natural hair as a defiant statement to History that had never allowed anyone looking like her to stand there. We might even infer, knowing her pride and sense of derision, that she let it float in the air as a snub to the insolent white children of the South who used to tell her that her hair was nappy and hideous.

Nothing in her showed any fear or anguish. She had come forward to the microphones in a poised and deliberate manner, displaying such confidence, you might think she had done this her whole life. Yet, she couldn’t have, as rarely any writer or person of colour had ever spoken in these auspicious ceremonies.

As soon as she began speaking, everyone in the audience, whether they knew her or not, stopped talking to intently listen to her, almost religiously, as she recited her prose.

Her poem ‘On the Pulse of Morning’, was written by her expressly for the inauguration of the 42nd President of the United States. In a few verses, she brilliantly retraced the history of America, taking the trees, rivers and rocks for witnesses of all these generations that lived before, and the tragedies that tore apart the children of this land.

” You, the Turk, the Swede, the German, the Scot

You the Ashanti, the Yoruba, the Kru,

Bought, sold, stolen, arriving on a nightmare

Praying for a dream.

Here, root yourselves beside me.

I am the Tree planted by the River,

Which will not be moved.”

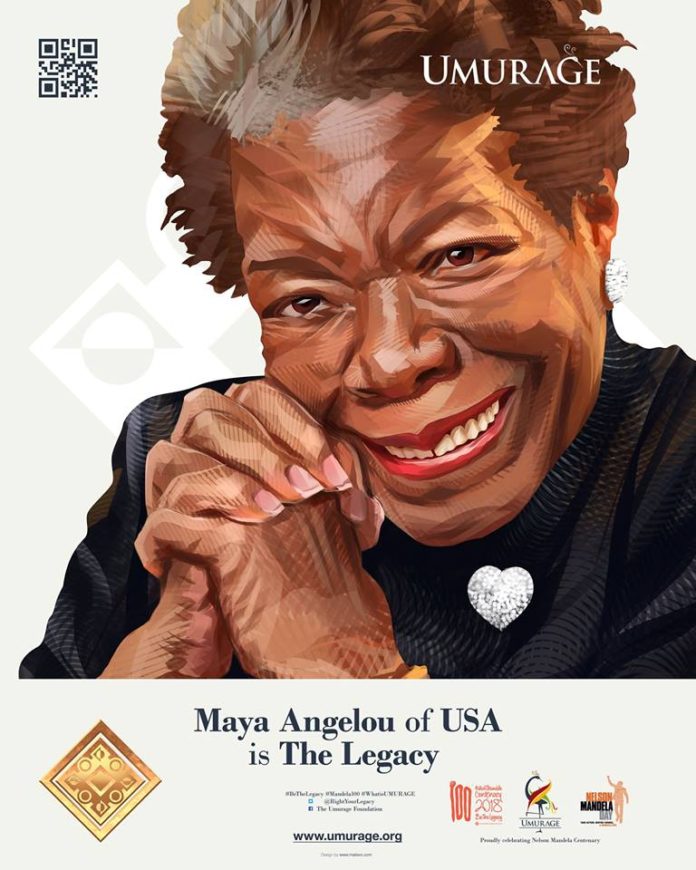

Her name was Maya Angelou, a name reminiscent of her African heritage and her refusal to remain anonymous in the crowd.

Aside from the fact that this was the official start of the first term of Bill Clinton, a native of Arkansas where she had spent part of her childhood, this opportunity was auspicious in more ways than one. First, Maya Angelou was the second poet ever to be invited to speak at a presidential inauguration. The first was Robert Frost – author of the poem ‘The Road Not Taken’ – and this dated back to the inauguration of JFK in 1961. More importantly, she was the first black American, man or woman, to receive this honour in the more than two hundred years since such events were organized.

In the history of the United States, only one black person had addressed such a crowd before, in this park that stretches for nearly two miles from the US Capitol and the Lincoln Memorial. It was this young idealistic pastor from Alabama who had dared to share his impossible dream with the world some thirty years before.

Although it was at this moment that the whole world discovered the voice that had already thrilled many Americans, it was only a few years later that her voice, her words and her story made an impact on the young refugee from Rwanda that I was then.

It must have been in 1997, I was new to Canada and I was discovering with delight the meandering of the English language. I remember seeing her in a television show, this septuagenarian with a timeless voice, reading her most famous poem in front of a public as fascinated by her as was the one at Clinton’s inauguration.

“You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

…

Did you want to see me broken?

Bowed head and lowered eyes?

Shoulders falling down like teardrops,

Weakened by my soulful cries?

…

Out of the huts of history’s shame

I rise

Up from a past that’s rooted in pain

I rise

…

Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.”

I was overtaken by powerful emotions, I never felt this way! I was like that person in Roberta Flack’s song ‘Killing me Softly’ – famously reprised by Lauren Hill and the Fugees – that person who went to a listen to a musician she had heard but never met, yet all his songs gave her the impression he knew her whole life.

And it wasn’t just the words, it was the voice, an extraordinary voice and unique, low and captivating, an acapella that resonated and amplified the simplest words more than any microphone could have done.

Her voice was like the blues, not a sorrowful blues but an exhilarating and joyful blues. It gave the impression that she had gone through time without taking a wrinkle, unscathed and unharmed by the tragedies she most likely endured to be able to feel the world the way she did.

Rarely has a poem touched me like ‘Still I Rise’ did. I looked for it at the library, memorised it and it became my own personal anthem. Until this day!

And what can I say about ‘Phenomenal Woman’, this celebration of Women and womanhood in the most glorious way?

“I say, it’s in the reach of my arms, the span of my hips, the stride of my step, the curl of my lips.

I say, it’s the fire in my eyes, and the flash of my teeth, the swing in my waist, and the joy in my feet.

I say, it’s in the arch of my back, the sun of my smile, the ride of my breasts, the grace of my style.

I say, it’s in the click of my heels, the bend of my hair, the palm of my hand, the need for my care.

’Cause I’m a woman, Phenomenally. Phenomenal woman, That’s me.”

She had the innate ability to bring to the surface the emotions buried deep inside of us, and give them a new, happier colour, helping us to accept circumstances that were far from light. I am also sure that many women found themselves silently reciting the words of ‘Phenomenal Woman’ before a job interview, an important meeting at work, when shopping, using public transport or parking her car, or any occasion a simple unfriendly look or comment can undermine us and make us feel like we are worthless.

It is one of those phenomenal women among my friends who sent me on the trail of the person behind this voice and her legendary texts.

And as every time my writings are solicited, I feel humble and somewhat anxious at the idea that perhaps I will not be able to accurately portray a person who touched so many and elevated our spirits in times we felt let down.

I usually start by reading articles and watching interviews online, but in her case, I wanted her to tell me her own story in her own voice.

Are you wondering if I am about to admit that a cartomancer or a medium turned tables for me and awakened Maya from the dead, just for a few moments? Or that I made an impromptu trip to the village to seek help contact this ancestor?

No, I won’t admit to any such thing. Not that I think of them as ‘pagan’ rituals, no. The digital era has given me other more practical options than those my ascendants used. I’ll let you guess how I did it. A bit of mystery never hurt anyone.

And what did I learn from my digital invocations?

Her life began on April 4, 1928 in the city of St. Louis, Missouri. When she was born, her parents Bailey and Vivian Johnson named her Marguerite Annie.

Vivian and Bailey Johnson divorced when she was three and soon after, Marguerite and her brother Bailey Jr, who was one year older then her, were sent to live with their maternal grandmother in a small town called Stamps in Arkansas.

It was a trip that could not be more unusual: imagine a little boy of four and his little three-year-old sister alone on a train with a note stating: ‘To whom it may concern, these two children are called Marguerite and Bailey Johnson, on their way to Stamps, Arkansas, care of Mrs. Annie Henderson’s.’

They hadn’t been alone the whole trip. Their father entrusted them with another passenger, but he got out somewhere along the way, leaving the two children with their handwritten note. Their father had moved to California while their Mother stayed in St. Louis and moved in with her mother. It was going to be several years before the children could see one another.

Grandmother demanded that everyone call her Momma, which suited them as she was to become their surrogate mother for many years to come. Momma Annie was a kind but austere woman who run the house with an iron fist. She got up every day at four in the morning, prayed and then woke up the children so they can accompany her to her store.

And yes, her store. It was the rallying point of the neighbourhood; the whole community shopped there, black and whites alike. It was a kind of grocery store, with all the products you can imagine. In the eyes of the children, the shop was very big. However, their grandmother was by no means a rich woman. She could probably have been better off, but most of her clients were blacks who worked in the mines and in the nearby cotton fields and very often, too often, she let them carry credit but pressure them to repay their debt.

Stamps was very different from St Louis. Not only was it a small town, but the children would quickly realize that it was segregated, with whites living on one side and blacks on the other. It was the reality of many southern US cities in the 1930s and beyond. Negroes were also denied many of their rights, but at that age the children were not aware of them.

The whites in the neighbourhood were mostly poor farmers, but that did not prevent them from being haughty and rude to the blacks. Even towards Momma Annie. Marguerite and Bailey, kids born in a large northern town, were offended when they saw how they spoke to her as if she were their servant. The white children, even the youngest ones, had the audacity to address her by her first name Annie-this and Annie-that as though she were their age. Their grandmother’s reaction, or rather lack of reaction, was as disconcerting as the attitude of these people; she did not snap at their rudeness. On the contrary, she called them Madam, Miss and Mister, and always thanked them for coming.

Momma Annie did not shrink or behave any differently with them that she would do with everyone else, but she seemed completely impervious to their insolence, as though she barricaded herself inwardly each time they appeared before her.

Marguerite remembers a day when she saw some of the little rascals, she often saw at the store walk towards their house. Their family lived on a farmland that belonged to her grandmother. They found Momma standing on her porch and start acting all crazy in front of her, pretending to imitate her grand-mother, exaggerating her expressions and making faces and derogatory hand gestures. One of the girls even showed her naked behind, but Momma Annie was standing still, quietly humming, her eyes set on the horizon. The children finally got tired and went away, shouting her name.

Marguerite was on the brink of exploding, but the glare of Momma Annie forbade her to even utter a single word.

She never explained to the kids why she acted like that. It was simply the way her grandmother and other Southern black folks had found to survive. Marguerite was too young to understand.

“Mom did not agree with the idea that we could answer the whites, because we risked her life by doing so. And certainly, they should not talk to them with impudence, even in their absence. ”

The Johnson siblings were as close as you can get, of that kind of unbreakable bond of children who felt abandoned by their parents. Marguerite adored her brother. When he was young, Bailey stuttered and could not pronounce her name, and even when he was trying to say, ‘my sister’, he only stopped at the word ‘my’.

Marguerite decided that her name would be Maya, a name easier to pronounce for her brother. Their lives were quiet and carefree, a life of two little children discovering a bizarre adult world and making a mockery of everything.

Sunday was dedicated to church. Their grandmother forced them to sit on the front row of the church so she could keep an eye on them and make sure they would not let any distractions stray them from the path of Christianity.

She had put them in school and insisted on the importance of studies in life. Their uncle Willy, their father’s brother, who had an accident in his childhood and was disabled, watched them while they were doing their homework. His accident had distorted his face and reduced mobility on the left side, but despite his disability, he was still able to catch them with his right hand to call them to order when he asked questions and saw them hesitating in their answers.

In the evening, Momma Annie sat in the living room and cut clothes she received from the whites folks to sew clothes for the children. She looked sad and faraway at times, but Maya had no idea why.

Maya and Bailey rarely heard any news from their parents. Sometimes their father and mother sent gifts, especially for Christmas, but these gifts made them sad rather than happy, making them wonder time and again what they had done for their parents to relegate them so far away.

Their father came to visit one day without any prior notice, some four years after sending them to live with his mother. Maya was then eight years old. He was a tall man with large shoulders, and very flamboyant with a brand-new car and tailor-made suits. He had one of these extroverted personalities, always in a good mood and telling jokes. She was in awe at the way he spoke ‘so correctly’, rolling the ‘R’s. The only person she knew who spoke like that was the school director.

The children were happy to see him. They were convinced that he had made a fortune in California and they were eager to see how their neighbours will be so jealous of him. It was not until she was in her teens that she learned that he was a doorman in a big building in California and lived a trailer. Like many people who visit ‘the village’ he had put on his best to impress those he had left behind.

However happy, his visit had triggered a new question, one they were afraid of the answer: had he come to fetch them or was going to leave without them?

At the end of the visit, their father announced that they were going to leave together and like that, without warning, he put them in his car and took the road. The children were eager to discover California and the ‘palace’ where they imagined their father was living, but to their surprise, he told them that he was taking them to their mother’s home in St. Louis.

The news filled them with anguish. They had become accustomed to the presence of this eccentric father, but they knew nothing of what awaited them at their mother’s house. What if she had remarried and had other children and would never care for them?

“I felt we were being taken to hell, and my father was the evil angel who took us there,” she thought.

We can say that Maya was already very melodramatic!

Their mother was beautiful and elegant, wearing makeup, all that Momma Annie had told them that a woman should not do. Maya was uncomfortable in her presence, but her brother was immediately at fond of her.

In fact, the girl felt self-conscious, she did not feel beautiful, and often wondered how two parents as beautiful as Vivian and Bailey could have given birth.

The children stayed with their grandmother, Mrs. Baxter, until their mother found a home. Their maternal grandmother was the opposite of Momma Annie. She was a light-skinned mixed-race woman, a nurse who worked in a large hospital in the city and lived in a big over furnished house. It was from her that their mother drew her beauty and elegance, thought Maya. The only thing she might have had in common with their maternal grandmother is that Mrs. Baxter was also a woman who commanded respect.

The grandmother and Uncle Willy’s strict discipline had prepared them for life in the city and for their new school. Toussaint Louverture Elementary School was larger than their school in Stamps, but their schoolmates were unruly and the teachers very rude to the children. The two children had read so many books and spent times doing the store’s accounting that they her much smarter than the other children in school. The school decided to put them in a higher class.

They called their ‘Madea’ (Mother Dear), a name that had the advantage of not confusing them as they kept referring to their grandmother as their Momma. Madea announced one day that it was time to move.

She took them to their new house, a house that they would she shared with her boyfriend, a man called Freeman.

Like their grandmother, their mother had trained as a nurse, but at the time she did not want to work in a hospital at all. She preferred to work as a waitress in a bar called ‘Louie’s’. She would sometimes take the children there and bring them in from the back entrance. They would stay there watching the movements of the crowd and look at their mother move about. Sometimes she would start dancing, always on her own, which apparently delighted the patrons.

Bailey and their mother continued to grow close, but Maya stayed reserved. She however made efforts to please her and try to get closer as her brother was. She went to the extent of letting her mother cut her hair very short like hers, although she felt a little ashamed to know that strangers could see her naked neck as she walks down the street.

Remember that Maya thought she was going to hell when her father took her to live in St. Louis? Well, she was somehow right, except that her mother wasn’t the one who was going to hurt her. She was going to meet the devil, in the form of a man, M Freeman, his mother’s boyfriend.

Mr. Freeman worked in a train company and made a good living. He took care of his darling, Vivian, whom everyone called Bibbie and her kids.

His whole life seemed to be centred around Bibbie. When he returned home from work, he would take his meal and seat in the living room to wait for her to come home. The children were busy reading books, but he did not read anything. He did not even listen to the radio. He was sitting and watching the door, waiting for his wife to come in. When she arrived, his face lit up.

It would have never crossed the mind of the eight-year-old girl that he had secret desires for her, so she was not suspicious of him.

Like a panther watching his prey, Mr. Freeman got closer to the little girl, little by little. One day, taking advantage of the fact that her mother had gone out and her brother was playing outside, the man took her by force, making her experience a pain she had never known before and left her in a state of shock, both physical and psychological.

After this infamous act, Mr. Freeman threatened to kill his beloved brother if she told anyone about what happened. She did not understand what was happening to her, and why he wanted to hurt Bailey.

The pain was so strong that the little girl went to hide in her room and swore she would never go out again. Her mother thought she was sick and told her that if it went on, she would have to take her to the hospital.

One day, while trying to change the sheets of his sister’s bed, his brother saw her underwear covered with blood and despite his young age – he was only nine years old – he understood immediately what had happened to his little sister.

“Tell me who did this to you, otherwise this man will hurt another little girl. “

When she told him that if she told him, the man would kill him, he calmed her and answered quietly:

“He cannot kill me. I will not allow to do it.”

She finally decided to tell him her terrible secret, and he began to cry. She had not cried till then, but her brother’s tears prompted her to let her tears flow. They stayed there together, two children lost in a hell that they did not understand.

The little boy showed extraordinary courage: he decided to go and see their grandmother and tell her what had happened. She was horrified and immediately called the police. Mr Freeman was arrested and sent to prison to await trial.

The girl was taken to the hospital and stayed there for days. It had become, by force of circumstances, her refuge from the house. Her family visited her every day, her mother and grandmother brought flowers and sweets and her uncles watched over her to prevent anyone from hurting her again.

Bailey brought books from the library and read them for hours, trying as best as he could to make her forget this episode, but she could not recover the innocence of her stolen childhood.

And even if she had wanted to forget, she could not have done it: the little girl was forced to appear in court and testify against Freeman, enduring embarrassing and intrusive questions in front of a wide audience, some who had come to support the family, and many more nosy acquaintances and strangers alike who had nothing better to do. It was in 1936 and the courts had not yet understood that exposing a child to public questioning was another form of violence against her.

Freeman was convicted and sentenced to one-year imprisonment, but he was only in prison for one day before he was released.

Four days after his release, the police came to see his grandmother to tell her that the man had been found dead after being beaten, but that no one knew who had done it.

It was too much to bare for the child! Not only had she kept the secret of what had happened to her for a long time, but when she had spoken, it had resulted in the death of a man.

” I had sold myself to the Devil and there could be no escape. The only thing I could do was to stop talking to everyone except Bailey. Somehow, I knew that because I loved him so much, I’d never hurt him, but if I talked to anyone else that person might die too. I had to stop talking.”

In her subconscious of an eight-year-old girl, she had associated talking and death, and it was completely beyond her.

At first, his family believed that her muteness was temporary, that it was just due to post-traumatic shock, but they ended up seeing that it had become permanent. When she refused to answer questions or failed to behave as before, instead of understanding her, adults would conclude that she was doing it on purpose. They even said she was insolent, and it often happened that an adult gave her a whipping or slapped her.

But the girl had made her decision and no mistreatment, no matter how brutal, could make her change her mind.

You surely think that it is not possible, that it is not the same Maya that we knew. How could a little mute girl ever become this extraordinary woman we are celebrating today, this woman whose voice still echoes from the distance?

We will get there, patience!

Finally, in desperation, her grandmother decided to send the kids back to Stamps at Momma Annie’s, hoping that at least there, the girl would speak again.

She found herself once again in a train heading south, alone with a brother who was grumbling about having to leave their Mother Dear but happy nevertheless not to be separated from his little sister bruised by life.

Although she was happy to be back in the country, away from the permanent noise pollution of the big city, she continued to be silent, whether at home, at school, as church or at the store. People ended up saying that she was putting on an attitude, snubbing people because she was coming back from the big city.

Maya was going to be silent for five years! So much so that everyone around her finally accepted that she would never speak again and stopped insisting.

Correction: not everyone. It is a friend of her grandmother, Mrs Flowers, who would take her out of her shell and bring her little by little back to normal, and so, in a very subtle way.

Mrs. Bertha Flowers was an educated black woman who spoke all the words perfectly, at least that’s how Maya remembers her.

Maya cannot tell when or why the woman noticed her, but one day she asked her grandmother if Marguerite – that’s what she called him, never Maya – could accompany her to help her carry her shopping bags.

Her grandmother nodded a little too quickly, which suggested to Maya that she was up to something with her friend. The girl followed her anyway, intrigued because she had never made such a request, she usually carried her baskets herself.

Her house was a real paradise for a little bookworm like her: there were more books than she had ever seen in her life.

Mrs. Flowers invited the girl to sit with her and keep her company. She took a book and read it out loud. In the end, she turned to the girl and asked her if she liked it.

Before she realized it was a trap, a kind trap but a trap nonetheless, the girl replied, ‘Yes, Ma’am.’

The words had come naturally but she did not regret talking. She felt secure in this house, and it was the first time in her life that anyone saw her for herself and not as Bailey’s sister, or Momma Annie’s child or Mrs Baxter’s grand-daughter. She felt visible, appreciated and loved.

Mrs. Flowers handed her a book and asked her to memorize it and to come and tell her aloud the next time she saw it.

She insisted that voice is the best way to communicate between human beings and that reading words was not enough, you had to read them out loud if you wanted to give them a real life.

Mrs. Flowers introduced her to books written by great names in American literature at the time, writers who would be her first influences the day she began to write.

Race relations were a topic high on Maya and Bailey’s mind as they were growing up in the segregated south. The authorities who came to speak at their school – all whites – consistently suggested that blacks should learn to stay in their place and that dreams only belonged to whites.

However, despite these demagogic speeches, Maya and her brother were convinced deep inside that only blacks themselves should determine what they can become.

Bailey witnessed a scene that would haunt him for years. The fifteen years old had seen the corpse of black pulled out of the river. The man had been killed by whites before being thrown into the water. White men were standing around his body and one of them pushed him with his boot to turn him over and see his face.

Bailey could not believe a man had been killed just because he was black, and even in death he was kicked like something you do not want to touch. The sheriff called the children and asked them to lift the body and bring it to the prison. He did not even want to tire himself to carry it, he preferred to leave children traumatized by the sight of this dead person, to lift him in his place! And all the while, the sheriff was joking with his friends, laughing loudly as if nothing had happened! How can people be denied dignity in life as in death?

In 1940, shortly after they completed their studies, their mother asked them to return to live with her. Their grandfather had passed away and their grandmother had decided to move her entire family to the city of Oakland, California.

They stayed there for a while, very happy to live with their loving grandmother Baxter once again.

Their mother remarried with an affluent black businessman – he owned several properties – and the little family moved to San Francisco, leaving their grandmother behind.

Maya was awarded a scholarship and continued her studies at a vocational school. The streets of San Francisco were also a great school for her. In the street, she learned the realities of life. And to her great delight, she learned black-spoken dialect and was happy to talk outside of school and back to a more formal English when she was in school.

Her brother and mother also encouraged her to take drama and dance classes, but she hesitated for a long time. She was still self-conscious about her physical appearance and thought the class would make fun of her. But her brother insisted, and she finally accepted.

She was amazed to see that no one cared about her demeanour and she could work on her movements without any shame. Finally, the experience was extraordinarily liberating! It was the beginning of a long love affair with dance and performances that would one day take her to stages all over the world.

Came the sad day where the siblings had to separate for the first time of their life: his beloved older brother, who was 17 years old , had decided to enlist in the navy.

In her last year of school, Maya became pregnant and decided to hide her pregnancy so that her mother would not force her to leave school. His son was born three months after graduation, when the girl was 17 years old.

She did not like the child’s father and never thought of asking him to marry her. She looked for work to take care of her son on her own.

In 1952, she married a European man, a Greek sailor. His name was Anastasios Angelopoulos and he dreamed of becoming a singer. At the time race marriages were strongly disapproved by society but she was in love and cared little about what people thought. Unfortunately, their marriage lasted less than three years.

After the failure of her marriage, she decided to embark on dance and music, and after a time singing in nightclubs, she was recruited by a performing art company and began an international career. Over the years, she would perform with several famous troupes and even appear in television shows.

She abandoned the name Marguerite Johnson and adopted the name of Maya Angelou (diminutive of Angelopoulos), a name she found more mysterious and better suited to a career on stage.

As she travelled around the world, she learned the languages spoken in the countries where the troupe performed. She continued her training in modern dance under the guidance of renowned choreographers.

In 1957, this multi-talented artist recorded a musical album, the first of her career, ‘Calypso Lady’.

But since childhood, her mind was set on becoming a poet, and she finally decided to move and settle in New York where prominent black writers of the time converged, so she too could become a ‘real writer’. She enrolled in the Writers’ Guild and it was long before she published her first poems.

It was at this time that she met a South African anti-apartheid activist, Vusumzi Make, and in 1960, she followed him to Egypt where he lived in exile.

She stayed there for a while, working as an editor for a local weekly newspaper. Their love affair was short-lived, but instead of returning to the United States, Maya decided to stay in the diaspora and continue to discover the continent of her ancestors.

She found a job in Liberia, but on her way there, she stopped in Ghana and fell in love with Kwame Nkrumah’s country. Like many other black Americans searching for their roots, she decided to stay and raise her son there.

“I cried out for my ancestors. Everything started here. The lynchings of America. The evils of my country, the eyes laden with white hatred, the hateful rejections based on the colour of the skin, the mockeries, the rights flouted, the lamentations and the loud moans inspired by the loss of a world, the inaccessible security. This long and terrible journey to misery, which was still going on, had begun here. I pressed my lips together to weld them to each other. The only manifestation of my distress was the burning tears that, like honey, slid down my cheeks. “

She started working at the School of Music and Theatre of the University of Ghana as Teacher and Administrative Assistant. She was also an editor for The African Review and during her stay in Ghana, she published articles for the Ghana Times and the National Broadcasting Company. She immersed herself so much in the life of this beautiful country of the Gulf of Guinea that she ended up speaking its main language.

In 1964, she decided it was time for her to return to the United States to participate in the civil rights movement. At the time, Malcolm X was one of the most prominent civil rights leaders, and his idea of creating an organization for blacks was getting momentum.

Unfortunately, Malcolm X was assassinated on February 21, 1965, just a few months after Maya’s return home, taking with him his grand dream of uniting blacks.

Maya decided to turn to Martin Luther King’s peaceful resistance movement. She assisted the movement in their communication, and, at the request of Reverend King, she served as one of the coordinators of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

In a tragic twist of fate, Martin Luther King was also to be murdered on April 4, 1968, on Maya’s fortieth birthday. She was devastated! Since that unforgettable day, Maya has decided to never celebrate her birthday again.

These near-miss encounters with death convinced her that it was time to pursue her passion and become a full-time writer. With the encouragement of her friends, she began to write the story of her life, daring to put on paper the odious crime she had been victim of at the tender age of eight.

‘I know why the Caged Bird Sings’ was an immediate literary success from its publication in 1969 until this day. Her biography inspired a movie by the same name and in 2011, Random House Publishing House published a magnificent audio version of the book, read by the author herself. That same year, Time magazine included it in its list of the 100 most influential English books since 1923.

Since the publication of her first autobiography, Maya Angelou has become a recognized and permanent feature in the American and international literary and academic circles.

However, it is impossible to reduce Maya to one single category. She was a jack of all trades, a gifted person who was not afraid to explore all the talents God had given her.

In 1972, one of her screenplays was made into a movie, ‘Georgia, Georgia’. It was the first African American woman to have her screenplay turned into a film.

She did not stop there. In 1977, Maya played a role in the televised adaptation of Alex Haley’s ‘Roots’, and in the 1990s, she appeared in hit movies such as ‘Poetic Justice’ and ‘How to Make an American Quilt’ . In 1998, Maya Angelou directed her debut film, ‘Down in the Delta’.

Her many awards include the world’s most exclusive literary prize, the Pulitzer Prize, and a Presidential Freedom Medal she received in2010 from the hands of no other than the United States first African American head of state.

And hold on, that’s not all. Maya Angelou won a Grammy Award for her poem ‘On the Pulse of the Morning’! I bet you did not know that a poem can get that kind of price? Well, yeah !

It is hard to believe that Maya Angelou has never attended University. It was her talent, and only her talent, that propelled her to the top of the American academic world, and she stayed there for several decades. Her charisma and perfect mastery of the English language in all its nuances earned her more than thirty honorary doctorates.

Since 1981, Maya has settled in North Carolina, where she held an Emeritus Professorship of American Studies at Wake Forest University.

She remained in her adopted state until her death in 2014.

The last poem she wrote and published was ‘His Day Is Done’, a tribute to the memory of her long-time friend Nelson Mandela whom she first met in the years before his imprisonment on Robben Island.

“The news arrived on the wings of a wind, unwilling to bear its burden,” she says in this heartfelt eulogy.

Life is a circle that never stops turning.

Maya, phenomenal woman, we will forever be grateful for elevating our minds and souls and allowing us to stand on your giant’s shoulders as we look forward to the future.

Contributor