Imagine you were born on the Atlantic coast of Ghana. Imagine your parents were so poor, they sent you, the last born of your mother’s 12 kids, to live with relatives. Imagine you were forced into slavery, working long hours as a fisherman, with no wage, no medical care, no schooling, and abuse like no kid should ever suffer. How long would you survive this harsh treatment? Would you ever be able to get out of that life? And if you did, how would you deal with the trauma? What life and what future would you have, you a kid robbed of his childhood and who can’t even read or write?

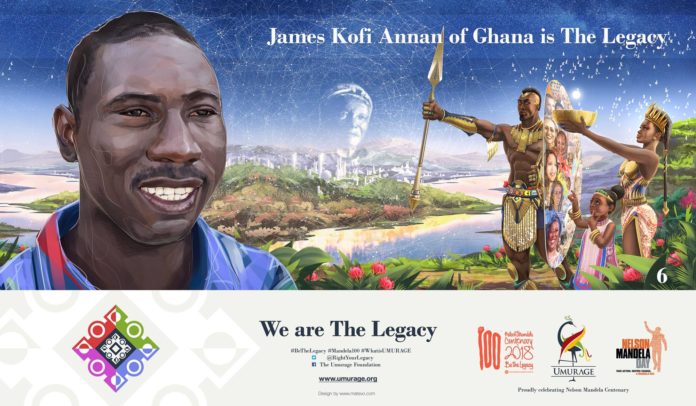

Today I am inspired by James Kofi Annan from Ghana. James was born in Winneba, a fishing port on the south coast of Ghana, in March 1974. He was the youngest of his mother, who had a total of twelve children. His father had many wives and many other children. His family was a very poor, and none of his parents or siblings had ever attended school. literate. As his parents struggled to raise their kids, they decided to send him to live with relatives near Lake Volta when he was 6 years old.

It was a common practice in those days, and it still is, for poor families to send their kids to stay with better to do kinsfolks. You might think that this was meant for the relatives to give your kid a much better life than the one you would have given them. The ugly reality is that most of those children were not sent to school but were rather put to work, making them forced bread-earners for their guardians. Another ugly unspoken truth about this custom was that most of these children were put to work in plantations so they could in a way pay for the hospitality they were afforded. The child was never to see any of his wages as any money made was paid directly to the family who placed him. A small portion of it would be sent to his parents back home.

That was to be the fate of young James as well. Lake Volta is a large 8,500 square meter man-made lake stretching from the south to the northern part of Ghana, said to be the largest man-made reservoir in the world. Given the abundance of fish in its water, fishing is an important activity for communities living on the lakeshore. The relatives who had taken him in immediately sent the little six years old boy to work as a child fisherman on the Lake.

“On a daily basis, my working day started at 3 am, and ended at 8 pm, and was full of physically demanding work. I was usually fed once a day and would regularly contract painful diseases which were never treated as I was denied access to medical care. During the time I was captive; I was tortured and abused in various forms.”

It was a very harsh world. They did all sorts of work, from preparing the nets and the boats, to fishing. They were expected to bring a certain amount of fish and when they didn’t, they were beaten-up or deprived of food. The same happened when they oversaw the fish nets; if one got entangled and they wasted time fixing it, which meant less time fishing and therefore less captured that day, they were severely punished.

“Despite the physical nature of the work, even though I was a child, I was still not expected to make a mistake. And anytime I made a mistake, I was tortured. As I was going through this situation, I saw that they found joy in torturing others. I saw adults kicking and hitting children with glee.”

Not all children made it out of that hell of a life, in the most literal sense of this common expression. James recalls that his guardians placed him with five other children, but three of the kids ended up succumbing from the abuse and the harsh working conditions.

Over that lapse of time, James was sent to more than 20 villages on the shores of Lake Volta. He tried to escape several times, but he was caught each time and was beaten-up by his masters, so he would think twice before trying to flee again. The punishment was also meant as a warning for other kids, to show them what would happen if they also tried to run away.

What I just described above is tragically a real-life definition of both child labour and modern day slavery. The International Labour Organisation describes “child labour” as any work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development. In its most extreme forms child labour involves children being enslaved, separated from their families, exposed to serious hazards and illnesses often at a very early age.

And the most tragic side of this is that his parents were part of the problem. Not only did they send him there, but they maintained him there, even when they saw from their own eyes during their visits what state he was in.

His mother’s visits were very emotional as she missed him and wanted him back home. She only came the first year he was away, but as after he started being sent to remote villages to work, she couldn’t see him anymore. He also saw his father; he would come occasionally, not to see his son but rather to collect his money. Most times, his father wouldn’t even talk to him. The young boy would see his father come and talk to the people who were holding him and then leave him there and go back home.

It’s only when he was thirteen that he finally managed to escape. That year, the head of the church that his parents attended, passed away. He was a prominent religious leader in Ghana and, as a symbolic gesture to show how much the man had touched people, the church asked that everyone who had a child named after the departed bring their kid to the funeral.

It was his lucky break as James was one of the kids named after the deceased. His parents came to look for him in his village near Lake Volta and took him to the place where the funeral was to take place.

Funerals are amongst the most important social events in Ghana. They are not only an occasion to mourn, but also an opportunity to celebrate the life of the departed. Mourners can come from across the country and the celebrations will take days before the actual burial.

The funeral of the pastor was to last a whole week. His parents were involved in the logistics of the funeral, so James took advantage of their distraction and the growing crowd of visitor to escape.

There was a truck transporting yam that had broken down near the village. James went and pretended to help them, waiting for the truck to be fixed so he could leave with them. Fortunately, they spoke his language and as they were chatting amongst themselves, he learned that they were heading to the coast near his village.

When they were ready to go, he casually asked them to drop him on their way which they agreed to do. In hindsight, he finds it shocking that some strangers took a 13 years old kid in their truck and dropped him somewhere without even knowing him or wondering why he was traveling alone.

When he got off the truck, he walked along the coast till he found his mother’s house and waited for his parents to return from the funeral. He knew his parents would try to take him back, but he was free, after seven long years of bondage, and he intended to stay that way.

His mother was happy to find him home but as he had suspected, his father was very angry at him and even tried to send him back. He stopped trying when he realised that the last seven years had given his son had the will of an adult.

“I was surprised that my mother was actually happy to see me, but my father was so angry. It was hell. They ended up getting divorced over it.”

Young James was angry too, angry at his parents for doing this to him but he didn’t say anything. Instead of fighting he wanted to use his energy somewhere else: school.

Since he was a kid, he wanted to go to school but he never did. He can’t tell how that idea came to his mind, as there were no positive role-models around him that could have awaken that in him. It was more intuitive than anything else, but he had the absolute certainty that an education would be his ticket out of this poverty cycle that had led him to be sold into slavery in the first place.

“In some ways, coming home was so easy – all I had ever wanted was to go to school, and being able to do that felt like the biggest achievement I could ever experience – just being in my uniform and having a book to write in was all that mattered.”

As his parents couldn’t pay for his education, he worked but this time it was for himself and not for any cruel master or to take care of his parents. It was for himself for his own education.

“I enrolled myself in school. I just wanted to go to school, so I started to take care of myself from that stage. When I started school, everyone laughed and mocked me but there was a deep motivation for me to learn. I didn’t mind what they had to say about how I looked or how poor I was. I just concentrated on getting knowledge and learning to speak English at any cost.”

You can easily imagine that paying for school was not the only challenge he faced. A bigger challenge was the fact that he was attending school for the very first time in his life at thirteen: the teenager couldn’t read or write.

“I was hugely disadvantaged compared to my peers. Trying to put aside all the pain I had felt during those seven years and catch up with school work while not having basics like food or clothes made things extremely difficult.”

And though he was living with his family again, there was never enough food and it could go for several days without eating. Despite all those challenges, he managed to do complete his primary and secondary school, finishing at the top of his class! It was a big milestone, for his age, for his background as a former child slave and for the fact that he was the only one in his family to ever step into a school let alone graduate from one.

“I did extremely well in school. Out of 200 students, nine were chosen to attend college so I went to the University of Ghana.”

James Kofi Annan earned a Bachelor’s Degree in Psychology! With that precious sesame in his pocket, he was ready to take on the world! But before looking for a job, the young man had to ‘give back to his country’: since the 1970s, it is mandatory by law for Ghanaian students who graduate from accredited institutions to do a one-year national service to the country.

Once he completed his year of service, James landed a job at Barclays Bank of Ghana and gradually rose to become a top executive.

This could be the perfect ending to a story that started in such a dire situation wouldn’t you say?

Well, not quite so.

Despite his managing to turn around his life and rise through society, James was still jaunted by his tragic childhood.

“It is something that is unimaginable. As an adult, I still lived with the menace of child trafficking. And sometimes the memory of the child enslavement I found myself in is so painful, I want to remove it! But it follows me everywhere.”

The pain made him realise he had to do something to alleviate the suffering of children going through what he went through as a child.

In 2003, he started an initiative to end child slavery in his native community.

“When I started, I just intended to mobilise children in the community and put them together to defend themselves against trafficking, to create awareness, and to promote education among them. We started with five children, and within a year, it had grown to 100 children. When we were working with 200 children, I decided to register the charity, and until then had been funding it alone. When we grew to over 1,000 children, my personal resources were no longer enough to sustain it, so donors began financing our work.”

Before he knew it, he was rescuing kids and putting them back in school. Within the first year, he put 50 kids back in school, using part of his bank salary and money he earned from a small printshop he owned.

‘Challenging Heights’ was born!

Despite the importance of what he was doing, the subject was taboo in Ghana, and many people, including the politicians who could have put an end to it, chose to pretend it did not exist.

It’s only in 2005 that that the government passed the Children’s Act to protect the rights of children and the Human Trafficking Act.

The two laws help them ‘negotiate’ with the child traffickers. Challenging Heights starts by explaining to the laws to them, how many years they could go to jail for if they are caught. They also try and explain to them the benefits to the community and to themselves if those children are released to go to school.

“In almost all the cases, the first answer is no. No because somebody has paid money to have that child to himself. And without that child, he has to pay hundreds and hundreds of times more than what he has paid for that child. So, his first answer will be no.”

It might take months before they agree to let the child go. You might wonder why go through that, why not simply call the police on them?

“If you don’t do that and the person has more children, maybe he is holding about five children and you have information on one, and you take that child by force and prosecute that person, you end up endangering the lives of the other four. And remember, at the same time, once there is a sale involved, the parent of the child who also sold him, has also wronged the law. He’s gone against the law. So, when you are prosecuting the fisherman, you should also prosecute the parent. Now the question is who would take care of the rest of the children when the parents are in jail?”

It is only those who are consistently recalcitrant that they call on for their prosecution as a last resort.

James knew he had to devote himself 100% to his cause if he wanted to really make an impact. In 2007, he surprised everyone when he resigned from his top job to run his organisation full time.

With the support from external donors, Challenging Heights opened a primary school in his native Winneba. Challenging Heights is meant for formers child slaves and children homes and communities that have a history of child trafficking.

Today, over 500 students attend the Challenging Heights School, between the ages of 4 and 15. In 2011, Challenging Heights opened a transitional shelter for 60 rescued children. It provides the kids with a loving and caring environment, counselling, education, and rehabilitation, and supports the reintegration process back into their families and communities. Many of the staff at Challenging Heights were victims of child trafficking and exploitation.

James also know that educating the kids is not enough. One must also fight poverty in the communities. He works with parents to help them find ways to support their families.

His work has helped him grow and heal, and quite unexpectedly, he has learnt to forgive the harm that was done to him as a child:

“I personally forgave my father before he died. I did that because, well, because of my faith and because I felt called to do that. I think doing that also helped me to progress in the work that I’m doing. But it was a very difficult thing to do. Knowing that your own father put you in that situation and even after I’ve come back, instead of he helping you to achieve your goal to go to school which is the right thing to do, he then rejects you and makes sure that the whole community rejected me and made sure that my mother did not have access to any resource to take care of me. That was a very difficult thing to accept that my own father could do that to me. But eventually, I did forgive.”

James hard work has earned him several awards and accolades as you can easily imagine. In 2006, he received the Barclays Bank Group Chairman’s Award – both for Africa and the Global award. In 2008, he received the World Association of NGOs Educational Award (WANGO 2008) and in 2011, he was the recipient of the Grinnell Young Innovator Award and the Michael Beckwith Africa Philanthropy Award. In 2013, his work earned him the World’s Children’s Prize.

One of his proudest moments was when he received an award from the hands of Desmond Tutu. The Nobel Peace Prize Laureate presented James with The Frederick Douglass Award, an award sponsored by the Free the Slaves organization, a Washington D.C. based non-profit organization working to eradicate slavery worldwide.

He went back to school to complete a complete his education at the University of Education in Winneba, where he earned a Masters’ Degree in Communication and Media Studies in 2009. In 2014, the year he celebrated his fortieth birthday, James was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Letters degree from Grand Valley State University.

It is estimated that Challenging Heights has supported over 10,000 children who have been slaves or at risk of slavery.

As many of our heroes, his story doesn’t end here as the Evil he is fighting is a monster that never sleeps. There are an estimated 49,000 children working in slavery on Lake Volta, the area where he was once captive and where he often returns to free other children.

So, he will keep on going, liberating one child at a time, and hope with all his heart that this most ugly form of modern day slavery and any other type of slavery will end in his lifetime.

That’s our hope too!

Right Your Legacy, James! You are the Legacy! #BeTheLegacy#WeAreTheLegacy #Mandela100 #WhatisUMURAGE

Contributors

Um’Khonde Habamenshi

Lion Imanzi