Timothy P Longman, Boston University

Paul Rusesabagina, who saved hundreds of Rwandans during the genocide by sheltering them in the hotel he managed – and saw his story made into the Hollywood film, ‘Hotel Rwanda’ – has been arrested by Rwandan authorities who allege “terror related offences”.

In an interview with Moina Spooner from The Conversation Africa, political scientist Timothy Longman – a top authority on the Rwandan genocide and its aftermath – provides insights into who Rusesabagina is and the build up to his arrest.

Who is Paul Rusesabagina and what role did he play during the genocide of the Tutsi in Rwanda?

In the early 1990s, Rusesabagina was the manager of a hotel in Rwanda’s capital, the Hôtel des Diplomats. Within hours of the plane crash that killed Rwanda’s president Juvenal Habyarimana on April 6, 1994, the president’s supporters spread throughout Kigali killing opposition politicians, civil society activists, and members of the Tutsi ethnic minority.

Many targeted people sought refuge in the country’s most prestigious hotel, the Hôtel des Mille Collines. With the hotel’s manager out of Kigali, Rusesabagina stepped in to manage the situation at the Mille Collines. Rusesabagina, a member of the Hutu majority, succeeded in keeping death squads out of the hotel. Ultimately over 1,000 people were safely evacuated.

In the aftermath of the genocide of the Tutsi, Rusesabagina was recognised for saving Tutsi lives. His story became the basis of the 2004 movie, Hotel Rwanda, with Don Cheadle portraying him. In 2006, he published an autobiography, An Ordinary Man.

Rusesabagina went on to become one of the best known Rwandans in the world. He travelled and spoke internationally, and received awards for his humanitarian work.

He eventually faced a backlash, however, as some survivors argued that he exaggerated his heroism. They also questioned his motives during the genocide, and criticised him for profiting from their suffering through self-promotion.

Why was Rusesabagina arrested?

After the genocide, Rusesabagina returned to his position as manager of Hôtel des Diplomats. I met him there in 1995 and heard from others, including several survivors from Mille Collines, the story of his saving people.

Rusesabagina was a political moderate, a Hutu married to a Tutsi. But through personal conversations, he told me he was increasingly troubled by what he saw as growing authoritarianism and anti-Hutu ethnic chauvinism of the post-genocide regime. In 1995, the Rwandan government used violence to close camps for displaced people. And in 1996, Rwandan troops bombed Rwandan refugee camps across the border in the Democratic Republic of Congo (then known as Zaire) and drove refugees back into Rwanda.

Rusesabagina left Rwanda in 1996 and received asylum in Belgium. But he felt threatened there and moved his family to Texas, where they settled.

There has been tremendous friction between Rusesabagina and Paul Kagame’s government.

Rusesabagina’s autobiography published strong criticisms of the post-genocide government. As a result the regime, led by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), began a concerted smear campaign, attacking his reputation.

Survivors from the Mille Collines began to challenge his actions during the genocide more forcefully. For example they questioned why he charged room fees to people staying at the hotel during the genocide. The survivor’s group Ibuka claimed that he was lying about his role in saving people and should be arrested, and Kagame even publicly argued that Rusesabagina’s claims to heroism were false.

Facing harsh criticism, Rusesabagina become increasingly harsh in his own condemnation of Kagame and the post-genocide government.

He spoke regularly about Hutu killed by the RPF, and his positions seemed to become more extreme. He even argued that there had been a “genocide against Hutu intellectuals”, a position that resembles the double genocide theory widely rejected by scholars.

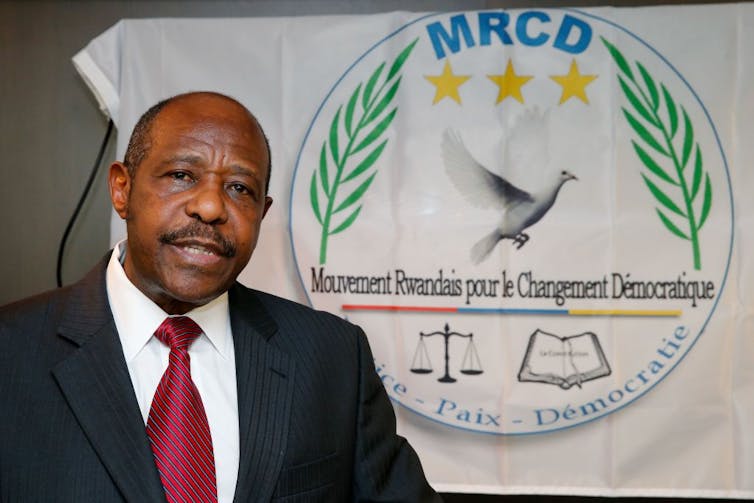

In recent years while living in Texas, he publicly supported opposition groups, like the Rwandan Movement for Democratic Change (MRCD), which he co-founded. His arrest stems from accusations that he has supported the Front for National Liberation (FLN), said to be the armed wing of the MRCD, and RUD-Uranana, an armed group that launched a deadly attack on Rwanda in 2018.

What is the significance of his arrest for Rwandan opposition? And what does political opposition in Rwanda look like today?

The details of Rusesabagina’s detention remain murky.

His arrest was announced in Kigali, but he appears to have been arrested outside Rwanda. His family have claimed that he was kidnapped in Dubai, but we don’t know yet whether he was detained by authorities in the United Arab Emirates on an international warrant and then turned over to Rwandan authorities or captured by Rwandan agents.

Many observers of Rwandan politics are suspicious of the charges against Rusesabagina, because the RPF regime has a record of using prosecution to intimidate opponents.

As I’ve written in my book, “Memory and Justice in Post-Genocide Rwanda”, the major challengers to President Kagame in each presidential election have been arrested and tried on trumped up charges. Former President Pasteur Bizimungu in 2002 and opposition party leader Victoire Ingabire in 2010 were tried on the vaguely defined crime of “divisionism” and imprisoned. Both later had their sentences commuted by President Kagame.

In 2017, businesswoman Diane Rwigara – a genocide survivor and women’s rights activist who attempted to stand as an independent candidate in the 2017 Rwandan presidential election – was charged with corruption. She was eventually acquitted on appeal, but only after spending a year in jail and having all of her family’s assets seized and auctioned off by the state.

The regime has also sought the extradition of critics living abroad and in some cases has kidnapped and repatriated opponents. For instance, former RPF official turned Kagame critic Patrick Karageye was assassinated in South Africa in 2014, while his associate Kayumba Nyamwasa survived at least two assassination attempts.

We cannot know for certain whether Rusesabagina provided material support to armed groups and supported terrorism, as he is accused of.

From my perspective, the tragedy of his story is that someone who took heroic actions to protect the lives of others became more radical because of unrelenting attacks on his character.

Sadly, in a political environment as polarised as Rwanda’s, there is no room for moderates and no space for critical voices.

Timothy P Longman, Professor of Political Science and International Relations, Boston University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.