By The Rwandan Lawyer

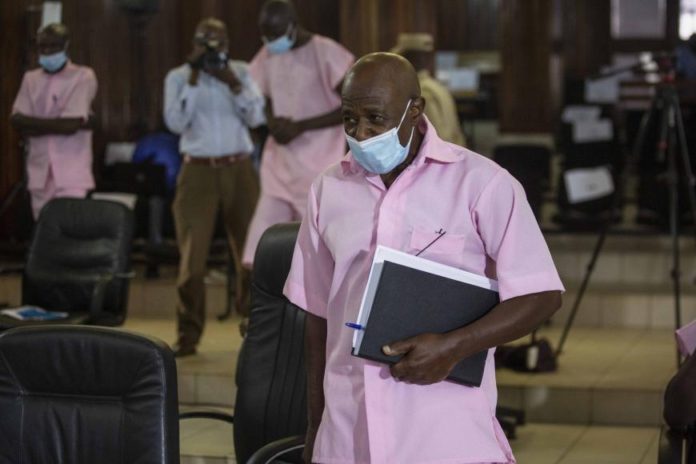

Paul Rusesabagina, the former hotelier who inspired the acclaimed 2004 film “Hotel Rwanda,” alleges he was tortured by Rwandan authorities for several days at an unknown location he described as a “slaughterhouse” after he unintentionally traveled to Kigali last August where he was arrested, according to the affidavit of one his Rwandan lawyers.

Practice of torture in Rwanda

Rwanda’s military has frequently held and tortured people, beating them, asphyxiating them, using electric shocks and staging mock executions. Most of the detainees were disappeared and held incommunicado, meaning they had no contact with family, friends, or legal counsel. Many were held for months on end in deplorable conditions. Rare survivors report what they endured in their inhumane detention.

Many of those tortured are forced to confess to crimes against state security and later transferred to official detention centers. Instead of keeping quiet, scores of victims dared to speak up at their trials. When the committee asked the Rwandan government why judges did not investigate when defendants said in the courtroom that they had been tortured – which the government is required to do under the Convention against Torture – the government simply presented a table in its report asserting that no one alleged they were tortured in trials from 2013 to 2017.

This stands in stark contrast to the facts. From 2011 to 2016, we documented 65 cases in which individuals said in court said they were illegally held in military camps or unlawful safe houses. Of those cases, 36 said they were tortured, beaten or otherwise forced to confess to crimes they did not commit. These were statements either made publicly in court during trials we monitored or are reflected in official court judgments.

In response to allegations, including by Human Rights Watch, about torture in Kami, a military base outside Kigali, the government wrote in its final report that it needed, “clarifications of these allegations… because the people who alleges [sic] to have been tortured… in The Kami Military Camp are unknown. Those reports did not provide names of victims and suspects; therefore, no investigations were conducted.” To Johnston Busingye, the justice minister who headed the Rwandan delegation at the committee, I say: please see Appendix I, pages 92-98 of our last report.

We provided the case numbers and the identity of those who dared to speak up in court. It is not difficult to confirm. That the government would simply say these people never spoke is the final act of torture. It denies them their right to tell the truth about what happened.

The government maintains it has no political prisoners. The government also says any case of enforced disappearance is investigated. Here again, recent facts tell a different story. Take the case of Theophile Ntirutwa, Kigali representative of the Forces démocratiques unifiées (FDU)-Inkingi, a banned opposition party. Ntirutwa was forcibly disappeared on September 6, after the arrest of several other FDU members the same day, and held incommunicado until September 23. During this period, the police would not confirm to Human Rights Watch or his family whether he was in custody.

He has now been charged with supporting an armed group. On November 21, during a hearing, Ntirutwa said in court, “I was disappeared for 17 days… My family was not informed of where I was, nor were human rights organizations. My wife told the police I had been disappeared. All that time I was blindfolded and handcuffed before it was revealed I was at [a] police station.”

These were words said in a public courtroom. The government should follow through on its obligations, open an investigation, and hold those responsible for this enforced disappearance accountable. But if recent history is any indication, chances are nothing will happen. Ntirutwa had previously been arrested on September 18, 2016, allegedly by the military, in Nyarutarama, a Kigali suburb. He said he was beaten and questioned about his membership in the FDU-Inkingi, then released two days later. Accounts of this detention were published, but the government did not investigate.

The committee wrote its final report that it is “seriously concerned” both about Rwanda’s failure to investigate allegations of torture and its “failure to clarify whether or not it opened an investigation into the allegations of unlawful and incommunicado detention.”

The committee’s concluding observations are cause for concern about the situation in Rwanda. While technically Rwanda has made advances in its legislation, in reality it does not seem to take seriously the absolute prohibition on torture. Rwanda is bound by both national law and international treaty obligations to act on allegations of torture and enforced disappearances, and to take steps to prevent such abuses. Instead of denying these abuses exist, it should demonstrate that it is ready to meet those obligations.

Specific facts in the case of Rusesabagina

Me Rudakemwa states in the affidavit that he intended to have a formal statement signed by Rusesabagina, but the situation at the prison “has deteriorated considerably, to the point where he was no longer allowed to visit him with privileged and confidential material in his possession.According to the affidavit, Rusesabagina told his lawyer that both the pilot and flight attendant said they were flying to Bujumbura. It was not until the airplane landed early on Aug. 28 that Rusesabagina said he realized they were at the Kigali International Airport. Rusesabagina said he then started screaming and tried to get off the jet but was restrained by RIB agents, according to the affidavit.”They tied my arms and legs, eyes and nose, mouth and ears,” he told his lawyer, according to the affidavit. According to the affidavit, Rusesabagina told his lawyer that he was taken to an undisclosed facility where he remained blindfolded and bound at the hands and feet until Aug. 31.”I call that place the slaughterhouse,” he said, according to the affidavit. “I could hear persons, women screaming, shouting and calling for help.”While at the “slaughterhouse,” Rusesabagina alleges he was deprived of food and sleep and was not allowed communication with his family or lawyers. At times, he said, his nose and mouth were also covered. When his legs would shake due to a lack of oxygen, Rusesabagina said an RIB agent would release the gag so he could breathe, according to the affidavit. Rusesabagina recalled one instance where an RIB agent allegedly stepped on his neck with military boots. Rusesabagina said he “was hardly breathing” by that point but could hear the agent say, “We know how to torture,” according to the affidavit.Rusesabagina also said he was unable to stand on his own and that someone had to hold him whenever he needed to defecate.”I lacked strength, I was suffocating,” he told his lawyer, according to the affidavit. Rusesabagina’s family and legal representatives said prison officials continue to deny him his prescribed medication for a heart disorder. They said he was also initially denied access to any of his chosen counsel and still has not been allowed contact with his international lawyers. He is provided limited contact with two Rwandan attorneys who are representing him in court. The privileged documents given to him by his lawyers are routinely confiscated in prison, according to his international legal team.

Analysis

Violations of the UNCAT

Between 2010 and 2016, scores of people suspected of collaborating with “enemies” of the Rwandan government were detained unlawfully and tortured in military detention centers by Rwandan army soldiers and intelligence officers. Some of these people were held in unknown locations, including incommunicado, for prolonged periods and in inhuman conditions. Torture and illegal detention are designed to extract information from real or suspected members or sympathizers of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR)—a largely Rwandan Hutu armed group based in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, some of whose members participated in the genocide in Rwanda in 1994—and, to a lesser extent, the Rwanda National Congress (RNC), an opposition group in exile, and the Forces démocratiques unifiées (FDU)-Inkingi, a banned opposition party.

Many were held at multiple locations during their detention, including at the premises of the Ministry of Defence (known as MINADEF), at Kami military camp, at Mukamira military camp, at a military base known as the “Gendarmerie,” at detention centers in Bigogwe, Mudende, and Tumba , and at private homes used as detention centers. Human Rights Watch is not aware of any Rwandan laws or statutes allowing for the military or other authorities to detain people at these locations. Severe beatings, electric shocks, asphyxiation and mock executions were used to force suspects to confess, or to incriminate others. Former detainees were held for up to nine months in extremely harsh and inhuman conditions, with insufficient food and water to meet their basic needs. Some survivors we succeed to meet reported that some detainees were killed and buried in mass graves. In many cases, after several months of illegal detention—and often only after detainees had signed a statement under torture—the Rwandan authorities transferred them to official detention centers, including civilian prisons, and they were then charged and put on trial. The period of their detention in military centers was erased from the public record.

Justice accomplice of torture authors

Rwandan courts infringe the provisions of article 15 of the UNCAT by the use of confessions where allegations were obtained through torture. Indeed, when before courts, the victims of torture who were forced to admit crimes they did not commit raise the issue of inhumane torture which occasioned such undue confessions, the public prosecution oppose the lack of proof of the alleged torture and the victims testify their unilateral testimony given that those abuses are committed in remote places, the victim being covered of mask so that he/she cannot identify the executioner. The sole proof may be perhaps the medical expertise but this one also should hardly indicate evidentiary data because there might be reported the state of the patient before and his situation after andnothing would establish the link between the consequences of the suffering undergone and the perpetrator denounced. Surprisingly in quite all claims, the judge dismisses the plaintiff even when he/she shows the scars of the serious blows that were inflicted against him.

The law deliberately lacunar

The law nº15/2004 of 12 June 2004 relating to evidence and its production especially in its article 6 reads that It is prohibited to resort to torture or brain washing to extort an admission from the parties or the testimony of witnesses but unfortunately this law does not offer means to detect those ill-treatments. Indeed, recently the Supreme Court of Rwanda recently issued an instruction on this matter ordering judges to consider confessions alleged by the prosecution as absolute proofs and reject any contestation from the suspects when the latter are unable to prove the torture they have undergone. It is pitiful coming from such a higher tribunal whose judges are aware that such victims are materially unable to establish expected proofs in circumstances they are found when under torture. The reason why Rwanda Investigation bureau officers; military police and intelligence officers regularly resort to torture in a perfect impunity covered by the weaknesses of the Rwandan evidence law.

Conclusion

Although Rwanda is party to the UNCAT and regularly publishes the UPR, there is regrettably a hiatus between those publications and the field reality: people suffer, people are tortured and killed in a perfect impunity in a country where courts first not independent are relegated to the last rank of decision-makers. Despite being told not to reveal the abuses they faced in detention, many of the defendants told judges they had been illegally detained or tortured in military detention centers but any judge cannot dare initiate investigations into such allegations. Military and intelligence officials responsible for torture benefit from the general climate of impunity and not worrying about any disciplinary or judicial action against them.