Imagine you were born in colonial Kenya, the daughter of a peasant family. Imagine that your parents were so poor, they made the choice to put their sons in school and leave you at home. Imagine that you finally went to school and rose to become one of the most educated women in the land. Imagine you become a community activist, and your stands for human rights and social justice made you the target of attacks by the rulers of your country. Would you be scared off and abandon your fight, give up and stay in the role of an obedient woman, as expected by your country’s culture? Or would you fight back for your beliefs?

“I was born the third of six children, and the first girl after two sons, on April 1, 1940, in the small village of Ihithe in the central highlands of what was then British Kenya. My grandparents and parents were also born in this region near the provincial capital of Nyeri, in the foothills of the Aberdare Mountain Range. To the north, jutting into the sky, is Mount Kenya,” she wrote in her memoirs.

“Two weeks into mbura ya njahi, the season of the long rains, my mother delivered me at home in a traditional mud-walled house with no electricity or running water. She was assisted by a local midwife as well as women family members and friends. Following the Kikuyu tradition, my parents named me for my father’s mother, Wangari, an old Kikuyu name.”

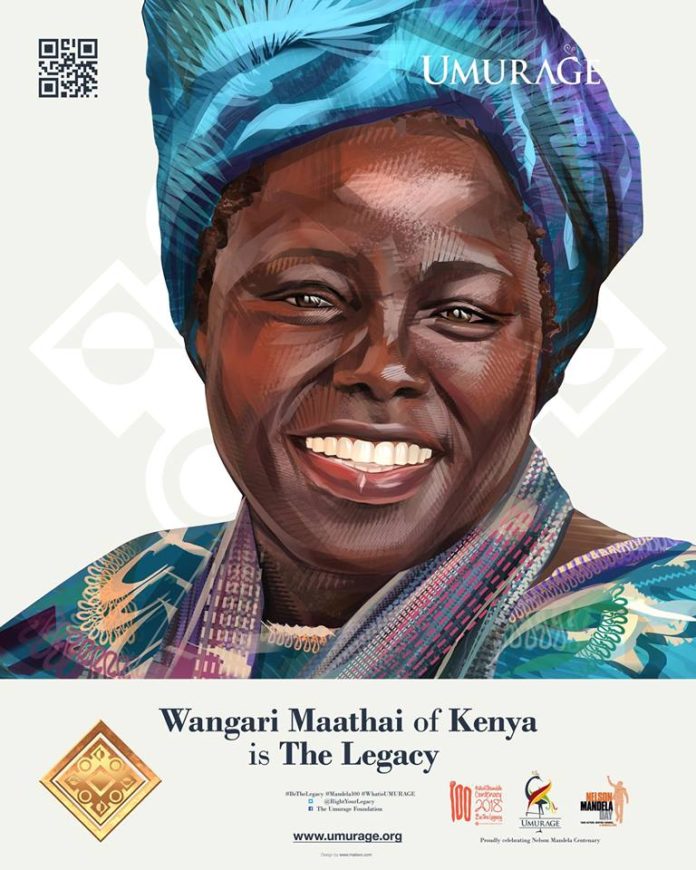

Yes, today, I am inspired by Wangari Maathai of Kenya. She describes her childhood village of central Kenya as a land lush, green, and fertile.

“We lived in a land abundant with shrubs, creepers, ferns, and trees, like the mitundu, mukeu, and migumo, some of which produced berries and nuts. Because rain fell regularly and reliably, clean drinking water was everywhere. There were large well-watered fields of maize, beans, wheat, and vegetables. Hunger was virtually unknown. The soil was rich, dark red-brown, and moist.”

When she was three, her family moved to Rift Valley, where her father – a farm labourer – had found work. When her two older brothers reached schooling age, her mother took the three kids back to their native village as there were no school near the white-owned farm where their father work.

Because of their meagre resources, her family had decided that only the boys should get an education. It’s after her brother persistently asked his parents why their sister was not in school, that she was finally able to join her siblings at Ihithe Primary School at the age of 8.

Young Wangari rapidly caught up with the other kids, gradually rising to become one of the best pupils in her school.

In 1951, Wangari was admitted to St. Cecilia’s Intermediate Primary School, a boarding school run by the Mathari Catholic Mission in Nyeri. During her time at St. Cecilia, Wangari converted to Catholicism.

The 1950’s was a time of change for Kenya. The country was still a British colony but the population was getting better organised to bring the colonial rule to an end. It was the time of the historical Mau Mau Uprising, a revolt that did not end colonization but played a big role in weakening Britain’s stand in the Eastern Africa land it had controlled since 1895.

Nyeri was affected by the instability and her Mother had to flee their village and find refuge in another village, but thank God, the boarding school was sheltered from the ongoing violence.

Wangari completed her studies at the top of her class and was admitted at Loreto High School in Limuru. Loreto High School was founded in 1936 by the Sisters of Loreto, a catholic congregation from Ireland, to educate African girls who, at that time, were denied the right to furthering their education beyond primary school.

Four years later, in 1960, Wangari completed her high-school, ranking among the top students in the whole country. The young lady received a scholarship to study in the US.

Wangari was passionate about science, an area dominated by men, but that did not deter her will. She obtained a degree in Biological Sciences from Mount St. Scholastica College in Kansas in 1964, the year Kenya became independent.

Wangari enrolled at the University of Pittsburgh where she earned a Master of Science degree in Biology . Wangari proceeded to complete a doctorate at the University of Munich, in Germany before returning to her home country in 1969.

Though she had an extraordinary academic track record at the time, she wanted to go one step further and make history in her own country. Dr Wangari enrolled in the University of Nairobi where became the first woman in East and Central Africa to earn a Ph. D!

Professor Wangari joined the University of Nairobi staff, first as a lecturer, and later as the chair of the Department of Veterinary Anatomy. She was the first woman to attain that positions in the region.

How did this academician become the activist who would change the world, one tree at a time?

Wangari started being interested in politics when she got married to Mwangi Mathai in May 1969, whom she had met a few years earlier when they were both students in the US. Mwangi Mathai aspired to become a join politician, and shortly after they were married, he decided to try to launch a bid for a seat in Parliament.

Though her husband lost that first bid, it was an enlightening experience for his wife. Especially the road trips during the campaign, where Wangari was able to see first-hand how too many Kenyans were struggling to have ends meet.

Professor Wangari Mathai started being more engaged in the fight for equal rights for women, starting with the University where she taught. She fought for women staff to be treated the same as male staffers. She went further and petitioned the courts to allow the academic staff association into a union, where all the voices of the staff could be heard and weigh in the future of the University, but the courts denied her request.

Wangari started taking more interest in what was happening outside campus, playing active roles in organisations such as the Kenya Red Cross Society, for which she become the director in in 1973, and the Kenya Association of University Women.

Wangari was invited to join the board of the recently established Environment Liaison Centre – body working to promote the participation of non-governmental organizations in the work of the United Nations Environment Programme headquartered in Nairobi – and was to eventually become the Chairwomen of the Centre.

In 1974, Mwangi Mathai tried his chances at a seat in Parliament and this time he won. Once again, Wangari followed her husband as he was campaigning, realising once again that her countrymen were living in the direst of situations.

She realized that most of the difficulties faced rural households were due to the scarcity of natural resources, resources that were once plenty but that were degrading at a fast pace, forcing people to walk miles to get access to basic things such as water or firewood. Most of the people impacted were women and children as they were the ones sent on those ungrateful errands.

The idea of using environmental restoration to create employment and wealth started forming in her mind.

The need was further confirmed when she visited her childhood village. She could not believe her eyes; the village barely resembled the green hills and valleys of her childhood.

“When I was growing up in Nyeri in central Kenya, there was no word for desert in my mother tongue, Kikuyu. Our land was fertile and forested. But today in Nyeri, as in much of Africa and the developing world, water sources have dried up, the soil is parched and unsuitable for growing food, and conflicts over land are common.”

The population had encroached on the forest to for farming, replacing the natural cover with fast-growing exotic trees that were degrading the soil and damaging the ecosystem. Instead of rural transformation and economic growth, these practices had led to desertification.

In 1975, she was invited to speak at an event a UN meeting that was being convened in Mexico City. During the preparatory event, Wangari met women coming from different parts of the country and asked them what they most were concerned about. Many of them told her that they needed firewood, clean drinking water, adequate nutritious food and better incomes.

She decided to act to address those crucial issues. On 5 June 1977, Wangari and the National Council of Women organised a women’s march downtown Nairobi, a march that ended in Kamukunji Park where they planted seven trees in honour of historical community leaders. This march was known as the “Save the Land Harambee” (harambee which means ‘”all pull together” in Swahili). It was the premise of what was going to be her biggest life achievement, the Green Belt Movement.

Through the Green Belt Movement, Wangari continued to encourage the women of Kenya to plant tree nurseries throughout the country, and with the support of friends and benefactors, managed to pay them a small fee for the work.

Wangari was also a very public critic of the ruling party, the Kenya African National Union (KANU), even though her husband was a member.

Then President Jomo Kenyatta had failed to fulfil the promise of turning Kenya in a democratic state. Almost a year after Kenya gained independence, his party, took near-complete control over the government. In 1964, Kenyatta used the legislature to gain considerable executive powers. He used those powers in 1969, when he unilaterally decided to end multi-party democracy in the country and Kenya became de facto a one-party state.

Elections were a real sham, as Wangari later described in her memoirs ‘Unbowed’:

“We hoped that these elections would provide the people of Kenya with a fairer and truer representation of their aspirations and beliefs. To our dismay and despair, however, the elections were the most disturbing and distorted in Kenya’s history. The government introduced a highly controversial system of “queue” voting. Voters lined up behind their candidate and election officials counted each line and then told the people to go home. When election officials announced the winner, it was often the candidate with the shortest line of voters behind him! Since the voters were at home, there was nothing that could be done: The winner had been declared. The vote- rigging was so blatant that people who had lost their races were declared the winners in broad daylight with no embarrassment whatsoever on the part of the government… I knew that we could not live with a political system that killed creativity, nurtured corruption, and produced people who were afraid of their own leaders. It would be only a matter of time before the government and I came in to further conflict.”

Her constant criticism of the party and personal problems in her couple let her and Mathai to divorce in 1979 after 10 years of marriage. Their divorce was bitter and much publicised. Mwangi Mathai is said to have acrimoniously called his wife “too educated, too strong, too successful, too stubborn and too hard to control” and other names I won’t repeat here.

Wangari took the words as a compliment and wore theme a medal of honour for the rest of her life. Bitter that she seemed unabashed by their separation and continued to publicly denounce the ways of politicians, her former husband sent her a letter though his lawyer demanding that Wangari stops using his surname.

Wangari decided to simply change her last name to Maathai instead of Mathai. There wasn’t anything he could do about that, she had technically followed the article of the law. He had forgotten that his wife was “too educated”, by his own words.

Wangari Maathai continued to fight for environmental, women’s rights and human rights issues, and continued to be a stark critic of her country politics. President Arap Moi, who replaced Jomo Kenyatta at the head of the country, did little to open the political space and had no patience for anyone who wanted to show that they knew better than government what the population needed.

She was going to come in his cross hair in 1989 when she protested a major infrastructure development in Nairobi. Wangari Maathai was infuriated to learn that the government was planning on constructing a 62-storey skyscraper in the middle of Uhuru Park, a recreational park situated in the central business district area of the Kenyan capital. The project was dear to President Daniel Arap Moi as it was going to showcase him as a visionary leader. The project included a statue of the autocratic ruler and it was said that the high-rise in going to be used as the headquarter of the ruling party.

Wangari Maathai saw this grandiose project as nothing other than a ploy to grab a public site.

She wrote letters of protests to everyone she could think of, from the Office of President to the representatives of the UN. She even called upon the British high commissioner in Nairobi to intervene as the major shareholders of the project were British.

The government ignored her letters but instead, she was the victim of vicious attacks in pro-government media. The President even called her a “crazy woman”, saying that it was “un-African and unimaginable for a woman to challenge or oppose men”.

The government found a way to force Professor Maathai and the Green Belt Movement to vacate the office she was leasing at the time.

That did not stop her or intimidate her. Wangari Maathai and other protesters did a sit-in in Uhuru Park and went on a hunger strike to protest the building project. The protest was met with violence and all the protesters were forcefully removed.

“It is often difficult to describe to those who live in a free society what life is like in an authoritarian regime. You don’t know who to trust. You worry that you, your family, or your friends will be arrested and jailed without due process. The fear of political violence or death, whether through direct assassinations or targeted ‘accidents’, is constant. Such was the case in Kenya, especially during the 1990s.”

The project was to never see the light of the day. All the foreign investors withdrew their pledges, scared of the backlash. The arrest of women for planting trees led organisations such Amnesty International to pressure the government to change its policies and law.

Ironically, during the protest at Uhuru Park, both Maathai and President Arap Moi were invited to attend the UN Conference on Environment and Development – the Earth Summit – in Rio de Janeiro. The Kenyan government tried to pressure the organisers not to allow Wangari to speak but in spite of their efforts, the academician turned activist was chosen to be one of the keynote speakers of the summit.

Wangari decided to try and change things from within the system. In 2002, she was successfully elected as a Member of Kenya’s National Assembly. In 2003, newly elected President Mwai Kibaki appointed her as Assistant minister for Environment and Natural resources, a position she held for three years.

Wangari continued to lead the Greenbelt movement, inspiring many to believe that you can save the world from itself, just by this simple gesture. through her work with the UN was able to bring the voice of African women onto the international stage.

She had earned more than 15 awards by the time she was appointed minister, including the Goldman Environmental Prize in San Francisco in 1991, the Hunger Project’s Africa Prize for Leadership in London in 1991, the Edinburgh Medal in 1993 for her “Outstanding contribution to Humanity through Science”, The Juliet Hollister Award in 2001, the Global Environment Award in 2003 from the World Association of Non-Governmental Organizations, and the Conservation Scientist Award from Columbia University in 2004.

Nonetheless Wangari – who was affectionally called her Mama Miti, “Mother of Trees” – never thought of herself as a big personality. She continued planting her trees, and that’s likely what she was doing in Octobre 2004 when she received the most unexpected of phone calls: a call from Ole Danbolt Mjos, chair of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, informing her that she had won the Nobel Peace Prize for her “contribution to sustainable development, democracy and peace”.

Yes, the Peace prize, not an Environment Prize. Professor Wangari Maathai, , had received the Nobel Peace Prize, becoming the first African woman to receive that award!

Her life changed overnight. Her name was on every media networks in the world, we were learning of her struggle, her fights to change her country mentality towards women.

“We were women”, she said in an interview, “we did not have any guns and we were not going to use force, even when they used force to try to stop us. We realized that all we needed to do to empower ourselves was to understand that we are the ones who can change government, we are the ones who can decide what kind of leaders to put in place. And so we got rid of our fear, we refused to be victims of government intimidation, but instead participated in elections and succeeded in changing leadership.”

The whole world learned of Wangari Maathai, with two ‘a’, the mother of three kids, an activist that had tried to save the planet one tree at the time. Her stage was no longer just her native Kenya, the world became her stage.

“I am immensely privileged to join my fellow African Peace Laureates, President Nelson Mandela and F.W. de Klerk, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the late Chief Albert Lutuli, the late Anwar al-Sadat and UN Secretary General Kofi Annan,” she stated in her acceptance speech.

“I know that African people everywhere are encouraged by this news. My fellow Africans, as we embrace this recognition let us use it to intensify our commitment to our people. Let us embrace democratic governance, protect human rights and protect our environment. I’m confident that we shall rise to the occasion. I have always believed that solutions to most of our problems will have to come from us.”

In the years following the Nobel Peace Prize, Professor Wangari Maathai spread her message across the five continents. She was appointed Goodwill Ambassador for the Congo Basin Forest Ecosystem, the world’s largest rainforest after the Amazon.

In December 2009, the UN Secretary-General named Professor Maathai a UN Messenger of Peace with a focus on the environment and climate change. In 2010, Professor Maathai became a trustee of the Karura Forest Environmental Education Trust, established to safeguard the public land for whose protection she had fought for almost twenty years.

Professor Maathai founded the Wangari Maathai Institute for Peace and Environmental Studies in 2010, in partnership with the University of Nairobi, an institution that will encourage academic research in areas such as land use, forestry, agriculture, resource-based conflicts, and peace studies, using the Green Belt Movement approach.

She received numerous honorary doctorates and authored four books including ‘Unbowed’, her autobiography published in 2006.

Professor Maathai passed away on September 25th 2011after a battle with ovarian cancer. She was 71 and by the time of her death, the Green Belt Movement has planted over 51 million trees in Kenya and her example had led to the planting of 11 billion trees worldwide.

She is survived by her three children, son Waweru, and daughters Wanjira and Muta Mathai. Her eldest daughter, Wanjira, serves as Chairwoman of the Green Belt Movement and the Wangari Maathai Foundation, launched in 2016 with a mission “to advance the legacy of Wangari Maathai by nurturing a culture of purpose and integrity that inspires courageous leadership”.

Rest in Peace, Mama Titi. Keep an eye on us, so we continue to pull together to colour this planet in the most beautiful of greens!

Contributor

Um’Khonde Habamenshi