Clayton Besaw, University of Central Florida and Jonathan Powell, University of Central Florida

Coups d’états have become increasingly rare across the world.

When coups – or even attempted coups – happen, they attract a great deal of attention. This includes a growing number of data sources and analyses dedicated to understanding the historical patterns and consequences of coups over the last century.

Not surprisingly, the data shows that coups can roll back democratic gains, escalate state violence, and stifle growth. They can also worsen economic crises and create political instability.

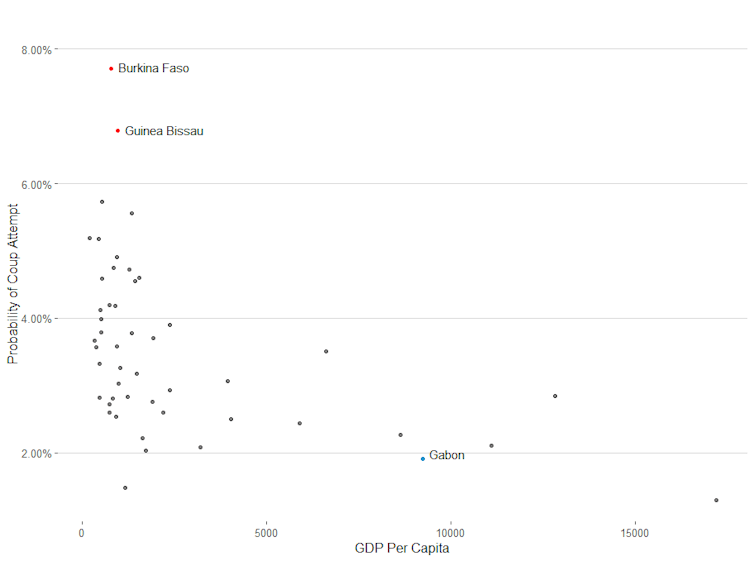

Given these negative consequences, the decreasing number of coups in the last decade should be celebrated. In the case of Gabon, a strong economy and relative stability suggested a regionally low risk of a coup attempt in 2019.

For 2019, our forecasting models suggest a further decrease in the risk of coups both globally and in Africa. That said, even the most powerful machine learning systems will have trouble foreseeing every coup in advance. The recent attempted coup in Gabon is a good example: on the scale of countries likely to have a coup in 2019, Gabon was ranked 47th in sub-Saharan Africa. Only Seychelles and Tanzania were regarded as being less likely to have a coup.

Further illustrating its stability, Gabon’s GDP per capita is strong. Only the Seychelles, Equatorial Guinea, and Mauritius perform higher.

Given the improbability of a coup in Gabon, and the failure of established economic and political predictors to anticipate it, we explore the reasons why the January 7 coup attempt happened. Furthermore, based on the analysis we’ve done on coups over the past 50 years, the fact that the Gabon coup attempt came as a surprise meant that it was much more likely to fail.

Why Gabon?

Before January 7, 2019, Gabon had not experienced a coup attempt in over 50 years. The last attempt to overthrow the government happened in 1964 when political opponents within the military tried to unseat President Leon M’ba.

While the plotters were initially successful, French President Charles de Gaulle quickly ordered a military intervention to restore the M’ba government. Motivated by oil interests and justified by a defence pact between the two countries, French paratroopers joined loyal Gabonese military officers and toppled the provisional regime within two days.

Supported by the French, the M’ba government contained the coup plotters and put systems in place to minimise future coup attempts. Gabon soon became one of the most stable and economically successful nations in post-colonial Africa.

So what led to this latest unrest?

Gabon coup plotters

President Ali Bongo – while considered to be an authoritarian – has maintained internal stability and economic growth.

That’s why predictions suggested a coup wasn’t likely in Gabon.

Looking at the country from the outside, the coup plot would certainly seem bizarre. But digging deeper, there were clues that it was on the cards. For one, President Bongo fell ill in October last year while attending an international forum in Saudi Arabia. Details about his condition were kept secret and the president didn’t return to Gabon as scheduled.

This sounded the alarm for the African Union and the United Nations. Both organisations asked the Gabonese political elites to exercise restraint and to respect constitutional process regarding the peaceful transfer of power. They did this to preempt a leadership vacuum because these have often opened the door to military intervention in Africa. For example, the death of leaders catalysed coups in Togo (2005), Guinea (2008), and Guinea-Bissau (2012).

In fact, Gabonese coup leader Lieutenant Kelly Ondo Obiang cited the leadership vacuum as justification for the coup plot following Bongo’s poorly received New Year’s Eve address where he appeared frail and unstable. In the eyes of Obiang, the president was no longer capable of carrying out his duty to protect the Gabonese democracy and to ensure political stability.

Like the plot against M’ba, the plot against Bongo failed quickly. Obiang’s revolution didn’t muster wider military support; nor did it incite a popular uprising.

While the plotters may have cultivated a strong internal narrative to justify a coup plot, they didn’t factor in the realistic odds of success given Gabon’s political and economic environment.

Surprising coup, unsurprising failure

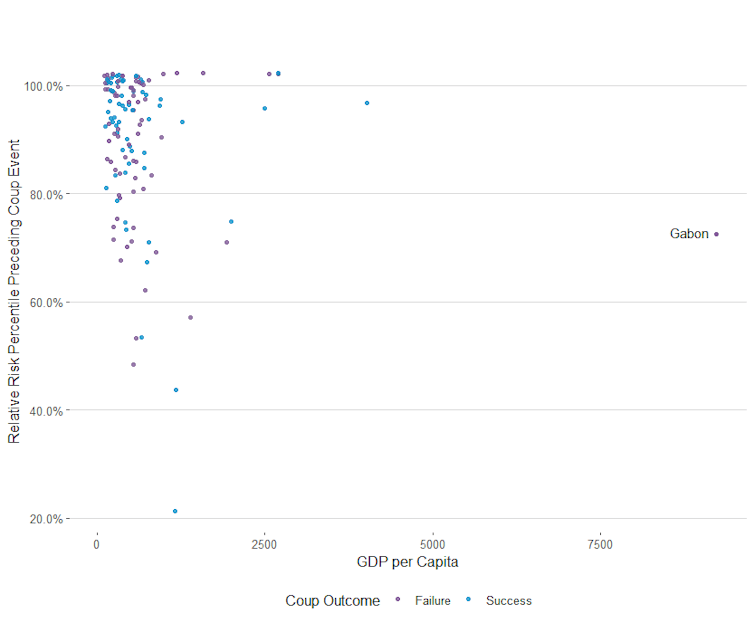

Compared to all African coup plots since 1950, Gabon’s latest experience deviates from the typical successful coup.

Looking at the relative risk preceding each of the world’s coup events since 1950, we find that Gabon’s percentile risk (72th) was nearly 23 points lower than the median risk percentile (95th) for all African coup events in the data. This suggests the conditions present in Gabon were far less conducive to a coup than the vast majority of previous attempts.

So why would the plotters take such a risky action? On the one hand, Naunihal Singh, Assistant Professor at the Naval War College and author of “Seizing Power: The Strategic Logic of Military Coups”, notes that risky moves can become successful if the conspirators can send credible signs to potential supporters that a coup will succeed.

This would have been difficult for Obiang given his conspirators’ relative anonymity and low rank. Singh recently stated that the plotters likely weakened their own credibility by admitting they had limited support when they asked the military and populace to rally behind their efforts. Instead of sending a signal of power, they acknowledged their weakness.

As regional hostility towards coup plots increases, alongside socio-economic development, we should continue to expect coups to decline and for coup plots to become riskier.

Our data suggests that this could certainly be the case. We found that when the relative risk preceding a coup event is lower there are more failed coups in Africa. When we examined coups that took place in the low-risk percentile, more than 60% failed.

______________________________________________________________![]()

Clayton Besaw, Research affiliate, Department of Political Science, University of Central Florida and Jonathan Powell, Associate professor, University of Central Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.