Imagine you were born in what was then called the Belgian Congo. Imagine that since you were a child, you wanted to become a doctor, so you could take care of your community. Imagine you get a chance to earn your medical degree and come back to practice in your local hospital, in South Kivu. Imagine the Congo war erupts in 1996, sexual assault because one of the most common weapon used by all the armed groups. What would you do? How would you deal with a level of atrocities you have never imagine could be done to women, cases your education and life never prepared you to?

Today I am inspired by Denis Mukengere Mukwege of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Denis was born in March 1955 in the southern town of Bukavu, in what was then called the Belgian Congo. Bukavu is the biggest town in South Kivu.

The son of a Pentecostal minister, Denis was the third of a family of nine children. Denis attended primary school at the Royal Grammar School in Bukavu. Though the Congo had gained its independence a few years before he started school, in 1960, the name ‘Royal’ was reminiscent of the recent past when the Central African giant was still a personal property of the King of Belgium.

Denis, who loved sciences, went on to study biochemistry at the nearby secondary school, the Bwindi Institute of Bukavu from which he graduated in 1974. He recalls that in those days, the Mobutu regime was still mighty and powerful and chose what and where every one should study. That’s how the state decided he would become an Engineer and sent him to study at the Polytechnic faculty of the University of Kinshasa.

It was a blessing of course to be able to attend university, but his heart was elsewhere than in engineering. When he was a child, Denis often accompanied his father to visit his parishioners and pray for the ill. He remembers how it was frequent to see women who had complications giving birth and not having proper medical care available to help them. Since then, his mind was set on becoming a medical doctor.

He was to stay at the University of Kinshasa a couple years, till 1976, before he finally left the Congo to go and attend medical school in Burundi.

Six years later, the new graduate came back home and joined the medical staff of Lemera Hospital, near his native town of Bukavu. Dr Mukwege first started working as a paediatrician, but he rapidly noticed that the mothers needed as much help if not more than their children. Similarly to what he had seen when he was younger, women routinely suffered pain after giving birth, and without the proper care, the complications were often lead to infertility when they weren’t fatal.

One year after returning back home from his studies in neighbouring Burundi, Dr Denis won a scholarship and went to specialise in gynaecology at the University of Angers in France.

One can say that that was really the turning point, that turn one makes in life that lead you to your destiny. That period was also a time where another well-known side of Denis was going to materialise, his humanitarian side. It was during his studies in France that he co-founded an association called Association Esther Solidarité France/Kivu to help his hometown.

Despite the appeal of better paid employment opportunities in France, Dr Mukwege mind was set on going back to his country after completing his specialisation. Which he did in 1989.

Not a fan of life in the capital, Dr Mukwege went back to his hometown and reintegrated Lemera Hospital where he started a brand new gynaecological wing and later became the hospital’s director.

When he opted to take care of women’s health, he wanted to bring down maternal mortality and thought the worst cases he would ever treat would be complications faced by mothers after giving birth. And indeed, that was the case for a few years till 1996, when the Congo war erupted.

It wasn’t long before the whole Kivu region, a region neighbouring Rwanda, Burundi and Uganda was completely engulfed in war, and Lemera would not be spared. In October 1996, the hospital was attacked by rebels. 35 of his patients – including pregnant women and other patients who were too ill to flee – and most of the medical staff were senselessly murdered, the medical supplies looted, the buildings – medical wings and housing – burned down.

Dr Denis Mukwege, who was amongst the few who miraculously survived the attack, fled the country and found refuge in Kenya.

The 41 years old physician could have counted his blessing and started a new life abroad, but he could not abandon his country, not now when it so desperately need all the people of good will. He recouped and started looking for support to go back to his country and take care of the hundreds of victims this war was making every day. His project: to build a new hospital.

His plea was heard: with the support of the national Pentecostal Church Organisation and the Swedish Charity Pingstmissionens Utvecklingssamarbete (PMU in short) amongst others, Dr Mukwege went back to his hometown of Bukavu and started the monumental task.

He had opted to build the hospital in Bukavu, instead of Lemera. Panzi Hospital – from the name of the district where it is located – opened its doors in 1999, some three years after the beginning of a war that continue to ravage his region some 22 years later.

It wasn’t a day too soon! Dr Mukwege was to quickly witness first hand one the ugliest sides of the conflict destroyed his beloved region in ways he would have never suspected when he was returning home, eager to serve his community. No longer after the opening of the hospital, Dr Mukwege was called upon to treat a woman who had been gang raped!

He was shaken beyond words by this case, not knowing yet that this type of cases would unfortunately become the norm rather than the exception for the rest of his career.

After he operated on the woman, in September 1999, the hospital started receiving an increasing number of women victim of such extreme and vile crimes. He estimates that his team and himself operated on 45 women just in the first three months.

“I had the impression that this was an enormous number, because I’d been in the region for a few years, and I’d never seen this before. It wasn’t until 2000 that I understood that this was normal, and I began to call on the international community.”

Forty-five seemed to be an enormous number at the time, but it wasn’t the highest they were to treat in the coming years. Since it opened its doors almost 20 years ago, Panzi has treated more than 85 000 patients, most f whom were victims of sexual crimes.

He decided to specialise in the care of women victims of sexual violence. The hospital expanded its mission to provide legal and psycho-social services to their patients.

Though his work is praised by his patients, who love him like a family member and whom he loves back, deep inside, he felt somehow unsatisfied. He knew that this wasn’t going to suffice. As a surgeon, he intervened after the fact. What he wanted was to be able to prevent these atrocities to take place in the first place. It was undoubtedly clear that mass rape had become a ‘normal’ weapon of war and it was getting worst, not better. Though the first atrocities were committed by the rebellion that overthrew the Mobutu regime, practically all the armed groups fighting to control one of the top mineral rich regions in the world, were doing the same. In 2011, the UN estimated that roughly 48 women are victim of sexual assault every hour in the Congo.

Parallel to his work at the hospital, Dr Mukwege became the de facto spokesperson of all these women he met daily basis, bringing to the world the horrendous tales inherited from this war.

His voice reached further than he could have ever imagined. The Congolese doctor nicknamed ‘the man who repairs women’, was invited to speak before the UN General Assembly first in 2006 and the second time six years later in 2012. From the New-York international stage, Dr Mukwege paid tribute to the courage of the half a million women who have been raped in Congo over the past 15 years and went on to denounce the international community, including his own government, for not putting an end to this hell and allowing perpetrators to roam free in the world.

“I would have liked to also say, ‘I have the honour of being part of the international community that you represent here,’ but I cannot say that. How can I say this to you – representatives of the international community – when the international community has shown fear and a lack of courage during these 16 years in the Democratic Republic of the Congo?”

As you can imagine, the miracle doctor doesn’t only count friends in the world. Speaking out like he does can even be fatal as he, almost, experienced it that same year. In October 2012, Denis and his kids survived an assassination attempt at his home in Bukavu.

He took his family to safety in Europe and came back to his hospital a few months later, in January 2013, more determined than ever. It was a king’s welcome! The population of Bukavu had come to wait for him at the airport and escort him back to the hospital with chants and traditional dances.

Since his return, Dr Mukwege lives on the hospital premises with a round the clock security details. His new circumstances often make him feel like a prisoner but he knows that it is part of the world he lives in.

Dr Mukwege continues to travel and shed light on the barbarity of the war on his country and in other parts of the world. In addition to the Panzi Hospital Foundation, which supports the functioning of the South Kivu facility, the doctor turned humanitarian is actively involved in an international human rights organization bearing his name, The Dr. Denis Mukwege Foundation. Created in 2016, the Foundation has for objective to end the use of sexual violence in conflicts around the world.

The Congo war is said to be the longest humanitarian crisis in history and the deadliest conflict worldwide since World War II, with more than 6 million deaths and countless victims of sexual crimes, including children.

In his autobiography, ‘Plea for Life’ (‘Plaidoyer pour la vie’), released in 2016 explained how distressing it is for him to the war to have gone on so long he, was now operating the daughters of some of his earlier patients.

Still, he won’t give up or give in to pessimism. He knows that a war is started by men and can also be ended by men. If they really want it.

His unyielding engagement and dedication has earned him several international prizes and accolades. In 2008, he received the United Nations Human Rights Prize, the Daily Trust African of the Year Award, and the Olof Palme Prize of Sweden. In 2011, he received the Clinton Global Citizen Award for Leadership in Civil Society, an award created by the former US President Bill Clinton to recognize extraordinary individuals who have demonstrated visionary leadership in solving pressing global challenges. In 2013, he was awarded the Right Livelihood Award and in 2014, the prestigious European Union Parliament’s Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, which honours individuals and groups of people who have dedicated their lives to the defence of human rights and freedom of thought.

Dr Mukwege was awarded several honorary degrees, including an Honorary Doctorate of Laws from the University of Winnipeg in 2014, in recognition of his role as an international voice for victims of sexual violence, his dedication to improving the lives and status of women, and his commitment to bringing peace to his country, an honorary Doctorate of Science from Harvard University in 2015 and an Honorary Degree of Doctor of Medicine from the University of Edinburgh in Scotland in 2017.

In 2016, the famed gynecologist won the Seoul Peace Prize, his name was included on the list of Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People in the world and was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. Yes!

Despite all these awards and degrees honoris causa, I am confident to state that his most prestigious prize is not monetary and doesn’t have a special name. It is the friendship that ties him to the women he has known through his work at Panzi. After the 2012 assassination attempt o his life, and his return to live in Bukavu, the women in his community vowed to be his best bodyguards. He knows they have no weapons and no means to fend or him, but their affection comforts him in this difficult path the war has forced then – his patient and him – on.

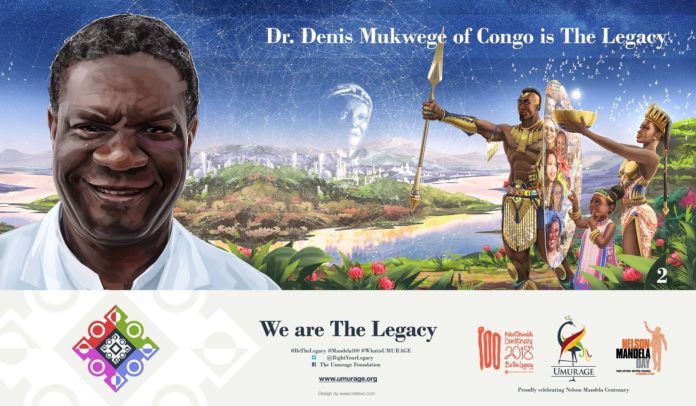

Right Your Legacy, Dr Denis Mukwege! You are The Legacy! #BeTheLegacy #WeAreTheLegacy #Mandela100 #WhatisUMURAGE

Contributors

Um’Khonde Habamenshi

Lion Imanzi