Imagine you were born in what was then called Nyasaland. Imagine your parents were so poor, they could not even afford to have a child. Imagine that your mother, out of desperation, decided to throw you in the river. Imagine you survived but went on to have the most difficult of childhoods. Imagine you dream to become a teacher you can help free the minds pf your fellow countrymen and countrywomen, but that opportunity is refused to you. What would you do? Would you accept your fate and live the simple life of a peasant , in the same fashion your parents and grand-parents did before you, or would you try the impossible to reach your dream?

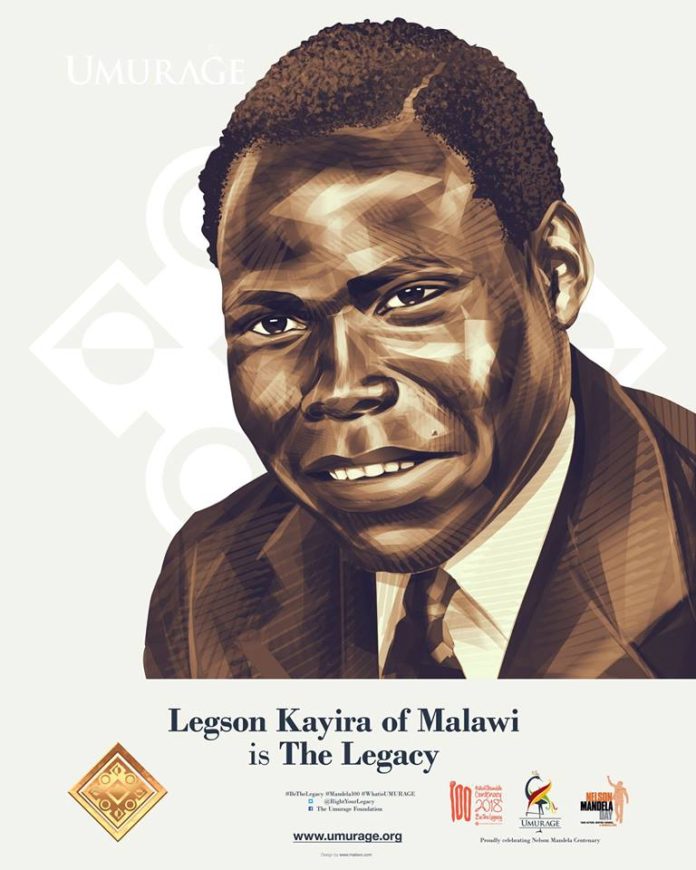

Today, I am inspired by Legson Kayira, son of Timothy Mwenekanyonyo Mwamalopa Arinani Chikowoka Kayira and Ziya Nyakawonga, born in a village called Mpale in the Karonga district of northern Malawi, near the Tanzanian border.

This story should start with the words ‘Habayeho ntihakabe’, once upon a time that should have never been, as it has all the makings of an African mythology, yet this story is nothing if not real.

In the early 1940’s, a baby boy was born in a poor family in the British protectorate of Nyasaland, which we now know under the name of Malawi.

At the time, his young mother Ziya Nyakawonga, was ill and too weak to take care of her heavy new born baby. In despair, she decided to throw him in the nearby river. She did not place her young one in a basket to be carried by the waterflow as in the story of Moses. She did not stay by the river to see what happened, she turned away and quickly went back home.

But like in Moses’ story, fate was watching over him: the baby floated on the water and was found by neighbour before he could drown!

They took him back to his mother, probably admonishing her for her desperate gesture. From there on, he was to be known as Didimu, by the name of the river that almost claimed his life.

Didimu had a very difficult childhood as you can easily imagine. His parents were both illiterate and lived of the meagre proceeds of their 20-acre farmland.

“I came from one of the poorest families that God ever created since the beginning of time.”

There was never any idle time or time to play for him. The moment he could walk on his own, his father taught him to plough the field and care form their crops. When he was old enough to hold a spear, he was thought how to hunt for wild hogs with spears so he can help feed his family.

On weekend, the young boy would look after his grandfather’s cows and sleep in a barn. He loved the time at his grand-fathers, though, especially the Saturday evening. That’s the time his grandmother would tell the kids country tales. Imagination was the only escape he could get from his dire circumstances.

The first gift his parents were to ever give him was to put him in school. The tuition was less than a dollar, but it had taken them a whole harvest to be able to afford it.

Wenya mission school was about eight miles away from home and Didimu almost gave up, but his parents never allowed him to entertain that idea. They knew school was the only way out for their son and were intent on seeing him complete his education.

The young boy got used to waking up before sunrise, completing his chores and walking for hours every day to attend school. After a while, he ceased to see it as an obstacle and started enjoying the seemingly boundless world he learned about in this school run by missionaries from the Church of Scotland.

Primary school was an important time of self-determination for the young boy. The first thing he did when he started reading and writing was to choose a new name for himself, so people who stop calling him by Didimu, a constant reminder of his first days on earth. It was often the case in those days that the European educators would arbitrary give you a ‘Christian’ name, but the young Kayira boy wanted his own unique name. He liked the word ‘leg’, so he created the name Legson, certain that the ‘son’ gave it an English consonance easy for his teachers to remember.

The second important thing he did was to choose a birthdate. Yes, you heard it right, choose a birth date. As it was the case in those days – and is still the case in many parts of the developing world – his birth was not officially recorded, and no one knew the exact date it had occurred. All he was told was that he was born during harvest time (May or June). He chose May 10th, 1942, as his date of birth.

Legson was a dedicated pupil and at the end of his primary school, his grades earned him a place at Livingstonia Secondary School, another school run the missionaries from the Church of Scotland. Livingstonia was founded in 1894 and it was named, as you probably guessed, after David Livingstone, who had famously “discovered” the source of the Nile alongside his compatriot Henry Morton Stanley. How anyone can discover a place already inhabited is beyond belief, but I diverge.

He was immediately captivated by the school motto “I Will Try”. He was going to adopt it as his own personal leitmotif for the rest of his life.

He loved reading and reading gave him an insight on a world he never knew even existed. The story Booker T Washington seduced him and instilled in him the idea one could free themselves from bondage.

You must remember that this was in the mid-fifties and Malawi, still known as Nyasaland, was a British protectorate federated with Rhodesia. It was only in 1964 that Nyasaland gained its independence was declared from British rule.

He decided that he was to become a teacher, not only as a way out of the farming life of his parents, but as a gateway to free the minds of the young ones and teach them about the world as he had been.

Regrettably, his application for the teacher’s college was refused. The reason he was given was that he was too young to become a teacher!

The young man, who had walked 8 miles a day back and forth to school when he just a young boy, was not going to be defeated by this rejection. If he could not study in his birth country, he would go and get his college degree abroad. And not anywhere in the world: in America, the land of the free!

“I saw the land of Abraham Lincoln as the place where one literally went to get the freedom and independence that one thought and knew was due him. One day I would also go there, I would also go to school there, and I would also return home to do my share in the fight against colonialism.”

When he was a teen, he was shocked that of the 3 million people in Nyasaland in those days, there were only 22 university graduates, and none of them from an American college.

“I want to be the first.”

Pause. Rewind. Study abroad? In America? In 1958?

You must be thinking that we skipped an episode where his family had made fortune and had money to send him abroad. No, they were still as dirt poor as they were when he was a child, if not more.

Did Livingstonia offer him a scholarship? No!

So how was a teenage boy from a small village where every single soul was poor, a boy whom, all his life, had tilled land and kept cows to help his family, going to afford a trip overseas? When he was unlikely to even have enough money to make a trip to the capital?

Well Legson made a decision that made everyone in the village think he had completely lost his mind: he was going to walk all the way to the US.

You can easily imagine how people made fun of him when he made his big announcement and how sorry neighbours probably felt for this poor family who sent their kid to school and he came back mentally incapacitated!

No one even knew where America was, not even his parents.

But the 16 years old had made his decision and nothing was going to change his mind. He chose a date for his departure, went about the village to bare his goodbyes.

On the fateful day of October 14th, 1958, he said farewell to his family and started what was going to be a journey of several thousand miles.

His mother did not believe he would go far. She laughed and said she was sure he would be back within a week. She did not know it was the last time she would ever see her eldest son. Life had not been kind to her; of her nine children, only Legson and two younger twins, a boy and a girl, had survived childhood. All the others had been successively swept away by illnesses.

Legson had studied a world map and his plan was to walk to travel North to Port Said or Alexandria in Egypt where he would look for work on a ship headed for New York.

He carried an axe, to cut through the forest, a small food provisions for at least five days, a map of the world and a map of Africa, a book ‘Pilgrim’s Progress from This World’, the religious book by John Bunyan, and his bible. He was barefoot, but proudly wore his school-uniform from Livingstonia for the trip, certain that the school motto “I Will Try” printed ion his t-shirt would bring him good luck.

Today, with the development of road infrastructures, the 800 miles between Northern Malawi and the Ugandan capital, his first stop on his way to Egypt, would take you less than a day drive. In those days, his journey was going to take him several months, walking and stopping her and there to do jobs so he could feed himself.

It was no easy journey, and many times he was home sick and worried about his family.

He reached Mwanza in Tanzania in July of 1959. He stayed in this port city by Lake Victoria for six months, working to earn enough money to buy a ticket on the steamer to Kampala, in what then called the Protectorate of Uganda.

“On January 19 in the year of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and sixty, I arrived in Kampala, a vast and impressive commercial city in the Protectorate of Uganda. The steamer anchored at Port Bell, only five miles away from downtown Kampala.”

It was in the wee hours of the morning, there was a cool breeze in the air, and he stayed on the deck for a second to admire the busy industrial neighbourhood which linked Kampala to other harbours on Lake Victoria and to the rest of the country via rail.

But quickly, his mind nervously came back on his journey and what waited for him the moment he would step on the pier.

“ My heart was throbbing with anxiety now, wondering whether or not I would be able to get into the city without any traveling documents.”

He stepped out of the boat and onto the quay and made his was to the Customs Office where the agents were yelling to the disembarking passengers: “Passes, passes!”

He was about to line-up and walk towards whatever punishment they had for undocumented immigrants, when he saw two men standing at the far end of the pier and waving at the group. They were yelling and calling for students to exit through the gate where they were standing.

This was his salvation. Legson joined the student’s line-up, and when he got at the front of the line, the man asked him if he was a school-boy, he nodded, and was allowed in the city.

Despite this ‘victory’, Legson was increasingly overwhelmed by this situation, though he was the one who had set it all in motion.

“I thus arrived in Uganda, my temporary destination, but America, my goal, was still far away, far away across land and ocean. I pulled out my map as soon as I was beyond sight of the suspecting Customs men. With my fingers I compared the distance I had covered and the distance still to be covered. I had come that far and there was no point in turning back now, I tried to console myself. At the same time, I pitied myself for having plunged into such a journey. The motto on my shirt still said, “I Will Try”, and I repeated the words as I had done now times without number: I Will Try. My shirt, however, was dirty, my shorts were dirty, and I was dirty.”

When he entered Kampala, he saw a young boy who was selling cooked plantain bananas:

“Matoke (bananas) for sale here”, the young boy yelled. A familiar scene even to this day, some sixty years later.

“I folded my map and after putting it back into the pocket went to the boy and bought a few bananas. Sitting down to eat my bananas, I pulled out my Pilgrim’s Progress and opened to my favourite page. “… and if you will go along with me, you shall fare as I myself, for there, where I go, is enough and to spare.”

He didn’t really know where to go next, but he knew reading those words, that he would be ok.

He decided to stay in Kampala for just a few days so he can figure out his next move. It started doing odds jobs here and there, preparing to continue his trip to the distant Egyptian port.

One day, he found a library and went in to get any information he could on studying in the US. He found a directory of American Universities, and he opened it, the first entry he saw was of a school called Skagit Valley College, in Washington State.

He followed the instructions and sent out an application letter. Hoping for the best but preparing for the worst, Legson kept on working and saving money.

To his big surprise, the school replied with a few weeks to inform him that his application was approved, and he was awarded a full scholarship, available once he was in the US.

Yes, the offer did not include any ticket to America.

Now that you know Legson, you can easily guess what his next move was to keep on walking his way North. He was emboldened and reinvigorated by his official invitation to the US. It was certainly not time to run back home or stay in Uganda for such a ‘solvable’ issue.

The young man learned that he would need to go to Sudan to get a Visa for the US, so he packed his bag and went on another journey by foot from Kampala to Khartoum. His first trip from home to Kampala was of about 800 miles, this leg would be of 1 600 miles!

An incredible sixteen hundred miles where he faced lions, hyenas, snakes, elephants, you name it!

By the time he reached Khartoum, two years had gone by since he’s left Malawi, he had crossed four countries and learned numerous languages along the way.

He made his way to US Embassy, he wasn’t met with a wall when he walked into the American Consulate, on the contrary. The diplomats were impressed when they heard he had walked all the way from an unknown village in Nyasaland, on the pursuit of an impossible dream.

The American consular officials were so impressed by his remarkable walk that they helped him get in contact with the College in Washington, which confirmed that his scholarship was still waiting for him. When they heard what he had gone through to come to the US – they hadn’t realised what his situation was when he applied for admission – they organised to get him on the next plane to America! The Embassy arranged for him to get all the necessary travel documents.

It was the most exciting and joyful moment, in his life. All the sacrifices he had made were going to pay off big time.

Some two years, four countries and eight foreign languages learnt since leaving his native village, Legson Kayira, born Didimu Kayira, the child his poverty-stricken family could not afford and almost got rid of as a baby, boarded a plane to the United States of America.

It was December 20, 1960, on a cold winter day, that the 18 years old dreamer was greeted at his arrival at Seattle-Tacoma Airport by the Atwoods, the family that was going to host him while he attended the college, and school officials, including George Hodson, the Dean of the College! He probably felt like a dignitary despite his humble demeanour and his old secondary school t-shirt that still read ‘I will try’.

He was an instant celebrity, in Washington State and across the whole country. Everybody wanted to see this young man who had walked 16 miles a day as a child and 2 500 miles across Africa, just to get an education.

While in Mount Vernon, Legson stayed on the family farm of the Atwoods, his adopted family. Bay View farm was nothing like the 20 acres field he grew up on, he helped milking the cows just for pleasure and not just to survive another day.

After graduating from Skagit College, Legson attended the University of Washington, where he earned a degree in Political Science.

In 1965, while studying at the University of Washington, Legson published his autobiography simply titled ‘I Will Try’, an eloquent account of this most extraordinary and epic journey. It was an instant success: ‘I Will Try’, remained on the New York Times bestseller list for 16 weeks after its publication. It was best-seller in the United States and England and was translated in numerous other languages since.

Legson went on to pursue his graduate studies in England, in no other than Cambridge University, where he graduated with a History degree in 1966.

He dreamt of returning to his recently independent home country, but then President Kamuzu Banda, who thought the writer to be subversive and did not like his open criticism of his regime, banned him from coming home.

Legson decided to stay in the United Kingdom, where he worked for years in the British public service, while pursuing his passion for writing. Following “I Will Try,” he wrote four novels and was working on a fifth when he passed away in October 2012, a couple days before the 54th anniversary of his departure from Malawi.

“They would reach their destinations sooner and merely by sitting down. I would reach my destination later and merely by counting my steps, but someday I would sit down and console myself that we both had reached our destinations, and this was all that mattered.”

Yes indeed.

*Contributor*

Um’Khonde Habamenshi