Aged of 90, the Rwandan Tycoon was declared unfit to stand the trial due to his mental inabilities medically determined and the court resolved to stay proceedings in a bid to monitor the evolution of his eventual recovery even if it was realized that the sickness is continuously aggravated and turns out to be irreversible. he court finds itself caught off guard, not knowing which legal text to base itself on or which case law to refer to. Notwithstanding, the decision to stay the proceedings sine die violates the rights of the accused. The present article strives to set out the various issues that arise from this complex trial which has become a headache for international magistrates and awakened the extremist demons of Kigali envious of legitimizing the looting of his patrimony.

Facts

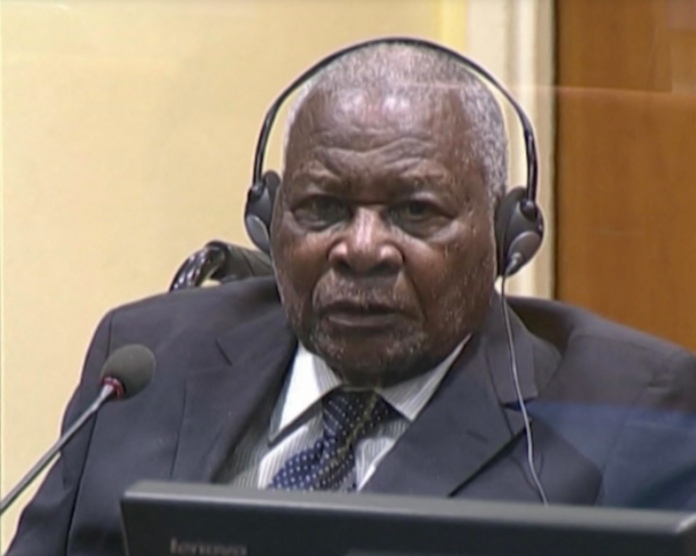

UN war crimes judges ruled that ageing Rwandan genocide suspect Felicien Kabuga is unfit to stand trial but should still go through a stripped-down legal process, in a decision announced Wednesday. Kabuga, who is 90, is a former tycoon accused of setting up a hate broadcaster that fueled the 1994 slaughter of around 800,000 people. Kabuga went on trial in The Hague in September last year, but judges said medical experts had now found that he had “severe dementia” and could not take part properly in court. The International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals said in an order that it therefore “finds that Mr. Kabuga is not fit for trial and is very unlikely to regain fitness in the future.”Judges said they wanted to “adopt an alternative finding procedure that resembles a trial as closely as possible, but without the possibility of a conviction.”It was important to victims, survivors and the international community that the genocide crimes against Kabuga still be addressed in court, the justices added. Prosecutors accuse Kabuga, once one of Rwanda’s richest men, of establishing hate media that urged ethnic Hutus to kill rival Tutsis and of supplying death squads with machetes. The businessman refused to appear in court or appear remotely at the start of his trial and has subsequently followed proceedings via video-link from a wheelchair at the court’s detention Centre. The court first put the trial on hold in March over health concerns, having earlier dismissed bids by Kabuga’s defence lawyers to have him declared unfit to stand trial.In their order on Tuesday, judges said three court-appointed medical experts had found that Kabuga’s mental abilities had “significantly deteriorated” since before the trial. The Rwandan was therefore unable to follow what was going on in court, understand evidence, instruct his lawyers or testify, it said. But the court said scrapping the trial altogether was “inappropriate”. They stressed the “importance of addressing the crimes against humanity and genocide charges against him to the victims and survivors of those crimes, and to the international community as a whole. The idea of an alternative legal process had already been tried in some Commonwealth countries and would respect Kabuga’s legal rights. Kabuga would not be required to attend the new legal process, the court added. Kabuga was arrested in Paris in 2020 after decades on the run and sent for trial in The Hague. He has pleaded not guilty to charges of being involved in an infamous Hutu radical radio station urging people to kill Tutsi “cockroaches” during the 1994 bloodletting. He also denied supplying machetes and otherwise supporting the murderous Interahamwe Hutu militia. Kabuga is one of the last Rwandan genocide suspects to face justice, with 62 convicted by the tribunal so far.

Analysis:

1) Immediate release

The prosecutor wanted to continue the proceedings “in the interests of justice”, but the defence asked for the proceedings to be halted and Kabuga to be released. Even if adult, the health conditions of Kabuga Felicien whereby he meets clinical criteria for dementia puts him in the category of people benefitting from criminal irresponsibility in criminal law such as minors of under 14 and mental patients who are de facto exempted from criminal prosecution. In this perspective, as he cannot stand trial due to his mental deficiencies, Kabuga deserves to be released and such a provisional liberty may facilitate his eventual recovery because the detention worsens his mental state in a sort of psychological traumatism adding to his excessive senility.

2) Indefinite stays

The court unduly resolved to submit Kabuga Felicien to a procedural stay which without referring to any similar precedent. Indeed, in cases before international courts involving unfit accused, courts have generally stayed the proceedings, maintaining jurisdiction in case the accused regained fitness. International courts that have adopted rules concerning proceedings after determinations of unfitness uniformly require such stays. During stays based on unfitness, accused are often held in custody and, if they are released, they are subject to restrictive regimes, including monitoring to determine continued unfitness. Cases in which international courts have stayed proceedings based on unfitness have virtually all involved accused persons who had a realistic prospect of regaining fitness. This case is different given that the Experts have determined that Mr. Kabuga’s dementia is progressive and irreversible and consequently he has no realistic chance of regaining fitness. Overtly, judges deprived of reference to base on disregarding rules and especially under political pressure of Rwandan Government decided to infringe fundamental rights of the accused patient!

3)Risk of arbitrary detention

Kabuga’s physical health and mental capacities have deteriorated significantly since their previous assessments, that he now meets the clinical criteria for dementia, and that he cannot meaningfully participate in his trial regardless of trial modalities or accommodations”, the court said. Paradoxically, the court decides to retain the accused patient in their premises in a dead end detention waiting for a trial on the merits which seemingly will not never take place. An indefinite detention following an unfitness decision in case of a suspension of the proceedings actually constitute an unlawful detention and exacerbates his health conditions which violates fundamental rights of Kabuga Felicien. In this regard, provisions of article 9 of the international covenant on civil and political rights are disregarded whereby It is not the general rule that persons awaiting trial must be detained in custody, but release may be subject to guarantees to appear for trial, at any other stage of the judicial proceedings, and, should occasion arise, for execution of the judgment. To avoid such an indefinite detention without any legal basis and without a foreseeable sentence to be served., the court should rather free him with judicial control where are imposed conditions so as to ensure his availability any time he is needed by the court.

4) The absence of legal grounds for an alternative finding procedure

there is no legal ground for a trial chamber to decide to set aside the regular trial procedure set out in the Rules, and replace it with an alternative finding procedure. While I note that Article 18 of the Statute provides the Trial Chamber with considerable discretion in relation to the management of proceedings as discussed above. There should not be considered that a trial chamber has such a discretionary power that enables it to create a completely novel procedure. The discretionary power enjoyed by the trial chambers in managing proceedings is not without any limits, as such discretion must be exercised in accordance with Article 18(1) and 19 of the Statute, which require trial chambers to ensure that trials are fair and conducted with full respect for the rights of the accused. It is worth to recall that Article 18 of the Statute states that trial chambers shall ensure that proceedings are conducted in accordance with the Rules of Procedure and Evidence. There should be emphasized in this regard that the Rules do not provide for such alternative finding proceedings. I consider that, in, the present case, the absence of legal basis susceptible of justifying the replacement of the trial by an alternative finding procedure, amounts to an abuse of discretion.

4) How to untie the knot?

The role expected from the Trial Chamber in these proceedings and its powers as recognized by the Statute and the Rules enables it to ensure the fairness of the trial and the respect of Kabuga’s rights. The common-law adversarial system entails a contest between two parties, prosecution and defence, where it is thus more important for the accused to actively participate in their own defence; opportunity which is not materially feasible within the mental inability of the accused. Besides, alternatives proposed by the court from domestic criminal procedures whereby the proceedings should go on in absence of the accused burdening the prosecution to prove the sole actus reus of the offence(facts-finding) or both actus reus and mens rea ingredients of the crime did never entail conviction and overtly were violating the right to a fair trial in a sort of masquerade trial. From the foregoing, I propose twofold alternatives. On one hand, the mental patient Kabuga deserves being judicially declared incapable and therefore be exonerated from criminal liability as well as minors under 14 and mental patients then the criminal prosecution would fall void.

Secondly, if the judge deems that the unconditional release of the accused poses a significant threat to society, he can order that the accused be provisionally freed on condition of hospital regular controls until he recovers or not the latter result entailing the alternative below.

On the other hand, as it is believed that the accused Kabuga will never recover, there can be recommended that a judge stay the charges against him. The trial will then be cancelled. We recommend staying the charges given that the accused is unfit and unlikely to recover, and that the judge renders the final decision thereon. If so, the judge can order a stay of proceedings and the accused will be released. However, this does not mean that the accused is acquitted for innocence because not judged on the merits.

Conclusion: the law still trapping itself

There occurs a certain discrepancy between the obligation of conducting a fair trial involving the individual appearance of the accused and right to defend himself against charges and provide evidence of his innocence before the court on one side and the duty to punish the crimes allegedly committed by the accused and therefore grant justice to his victims on the other side. However, under presumption of innocence and having pleaded non-guilty, Kabuga raises a legal dilemma that traps judges and directs them in a dead end tunnel: either he would be declared innocent and acquitted if effectively judged all his rights to due process respected or convicted or consequently be liable to pay the incommensurable billions of Rwandan francs to victims whose legal counsels foolishly and shamefully recently seized the intermediate court of Gasabo prematurely requiring such innumerable amounts for alleged damages arising from a non-existent criminal judgment!