Acknowledge his Detention; Ensure Access to Lawyer; Block Any Return to Rwanda

(Nairobi) – A Rwandan asylum seeker and founder of an opposition movement, who has been forcibly disappeared by Mozambique authorities, risks being handed over to Rwanda, where his rights would be violated, including by being subject to an unfair trial and arbitrary detention, Human Rights Watch said.

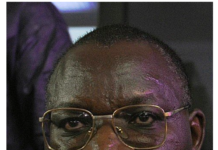

Although the asylum seeker, Cassien Ntamuhanga, was taken into custody by Mozambican police on May 23, 2021, the authorities have denied knowledge of his detention, and his whereabouts are unknown. The Mozambican authorities should urgently acknowledge Ntamuhanga is in their custody, reveal his whereabouts, allow access to a lawyer, ensure that his due process rights are respected, and prevent any forced return to Rwanda.

“The Mozambican police should protect this asylum seeker, who is at serious risk of harm if returned to Rwanda,” said Lewis Mudge, Central Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “It would be unconscionable, and a violation of international nonrefoulement obligations to hand him over to the police force of the country whose persecution he fled.”

Four sources who saw Ntamuhanga shortly after his arrest said that seven Mozambican agents with SERNIC (the National Criminal Investigation Service) identification cards and wearing uniforms took Ntamuhanga to the local police station on Inhaca island. Police officers told neighbors who accompanied Ntamuhanga to the station to leave.

He was then transferred off Inhaca island, 37 kilometers from Mozambique’s capital, Maputo, by boat, they said. They said that a man in civilian clothes was also present at the time of the arrest and in the boat, and one source who heard him speak to Ntamuhanga said they spoke the same language, indicating that it may be Kinyarwanda. The source said Ntamuhanga was handcuffed and his legs were chained together.

Both the Mozambican police and SERNIC have denied having Ntamuhanga in custody since his arrest, despite multiple attempts by his lawyer and the Association of Rwandan Refugees in Mozambique to locate him. On May 28, a spokesman for the investigation service told journalists that his institution “had no record of an operation to detain Rwandan citizens.” Ntamuhanga’s lawyer has written to the Maputo city prosecutor general but has not been able to determine his client’s whereabouts. Mozambique’s national human rights commission wrote to the head of police, the prosecutor general’s office, and SERNIC, but said they received no response. A local media report said that Ntamuhanga was handed over to the Rwandan embassy in Maputo on June 1, but Human Rights Watch has not been able to confirm this.

When authorities deprive someone of their liberty and refuse to acknowledge the detention or conceal the person’s whereabouts, they are committing an enforced disappearance, a crime under international law and prohibited under all circumstances. Those involved in and responsible for such acts should be held criminally responsible, Human Rights Watch said.

Ntamuhanga was convicted in Rwanda after a highly politicized trial, alongside the singer and activist Kizito Mihigo, in February 2015. He escaped from prison in November 2017 and fled to Mozambique. Mihigo was pardoned in 2018 but re-arrested while trying to flee the country in February 2020, and died in police custody in suspicious circumstances four days later.

Ntamuhanga’s prior conviction, the fate of Mihigo, and Rwanda’s track record of ruthlessly targeting critics and dissidents across the globe are reasons to be gravely concerned for Ntamuhanga’s safety, Human Rights Watch said.

Ntamuhanga’s disappearance falls into a well-documented pattern of attacks against critics both in Rwanda and abroad. The victims of the attacks abroad have tended to be political opponents or outspoken critics of the Rwandan government or of President Paul Kagame himself.

High-profile cases include the assassinations of former Interior Minister Seth Sendashonga in 1998 and the former external intelligence chief Patrick Karegeya in 2014, and the attempted assassination of the former army chief of staff Kayumba Nyamwasa in 2010, the former in Kenya, and the latter two in South Africa. A Rwandan military officer connected to Karegeya’s case was questioned by Mozambican authorities in January 2014.

In October 2012, the former Rwandan Development Board managing director, Théogène Turatsinze, was found dead and tied up with ropes in Maputo two days after he was reported missing. A US State Department report said that “Mozambique police initially indicated Rwandan government involvement in the killing before contacting the government and changing its characterization to a common crime.”

Mozambique’s forced return of a detained Rwandan asylum seeker to Rwanda without basic due process would violate the international legal prohibition against refoulement, the forcible return of anyone to a place where they would face a real risk of persecution, torture, or other ill-treatment, or a threat to their life. Ntamuhanga is a registered asylum seeker with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and had been awaiting refugee status determination by Mozambican authorities.

Under the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which Mozambique and Rwanda ratified in 1999 and 2008, respectively, no one is to be sent to a country where there are substantial grounds for believing that they might be tortured or mistreated. This obligation has been interpreted to require governments to provide a system for people to challenge decisions to transfer them to another country.

While Ntamuhanga’s refugee status determination is pending, nonrefoulement obligations still apply. The Mozambican authorities should urgently disclose Ntamuhanga’s whereabouts.

Ntamuhanga should be subject to a formal extradition procedure in a Mozambican court, including consideration of the human rights implications of the transfer, his asylum seeker status, and the risk of abuse and an unfair trial that he faces in Rwanda, Human Rights Watch said.

“It’s clear from the government’s previous treatment of Ntamuhanga that he is at risk of persecution in Rwanda, and there is cause to be worried about his safety in Mozambique,” Mudge said. “The Mozambican authorities should publicly disclose his whereabouts, allow him access to a lawyer and visits by relatives, and, if he is to be charged, promptly bring him before a court.”

Ntamuhanga’s Political Persecution

Ntamuhanga is the former director of Amazing Grace, a local Christian radio station. He co-founded the Rwandan Alliance for the National Pact-Abaryankuna, an opposition movement created with other Rwandan youths that says it focuses on ethnic reconciliation for victims of all violence during and after the genocide.

Ntamuhanga, Mihigo, a singer and activist, and Gérard Niyomugabo, who hosted radio discussions with Ntamuhanga about ethnic reconciliation in Rwanda, were arrested in 2014 after Mihigo released a song that expressed compassion not only for victims of the 1994 genocide, but for all who have died, “be it by genocide, war, slaughtered in revenge, vanished in an accident, or by illness.” The song was widely interpreted as a Tutsi genocide survivor showing sympathy with Hutu who were killed by soldiers of the current ruling party, the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF).

Ntamuhanga was tried in a high-profile and politicized trial alongside Mihigo and two others in 2014. Ntamuhanga was convicted by the High Court in Kigali in February 2015 of forming a criminal gang, conspiracy against the established government or president, complicity in a terrorist act, and conspiracy to murder, and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

Niyomugabo, who was detained at the same time as Ntamuhanga, has been missing since. In a September 2020 interview, Niyomugabo’s mother said she fled Rwanda because after his disappearance, military officers would come to her house every night and local officials told her to go into exile. She said that before his disappearance, Niyomugabo told her he knew he risked being killed because of his work on reconciliation.

During the trial, Ntamuhanga pleaded not guilty and described his week-long incommunicado detention in “Kwa Gacinya,” a police station that often serves as an informal prison in the Gikondo neighborhood of Kigali, after his arrest in April 2014. He told the court he and his colleague Niyomugabo were tricked by the police, detained, and taken to Kwa Gacinya, where he said he was chained and kept in a dark room. He told the court he was forced to sign a confession under duress, but the judge dismissed the claim and did not order an investigation. Human Rights Watch has documented dozens of cases of incommunicado detention and torture at Kwa Gacinya since 2012.

Asked about his time in incommunicado detention, Ntamuhanga said in an interview on YouTube: “They told us: ‘You, young boys, what did the government do to you? The government sponsored your education, you have good jobs, and now you start collaborating with the country’s enemies.’ … [They said] they will rehabilitate us after we confess to the crimes.”

The abuse described by Ntamuhanga matches Mihigo’s accounts of severe ill-treatment and due process violations during the same time period, which Mihigo shared in an audio recording with Human Rights Watch. Mihigo said he was threatened by senior government officials, beaten, and told to ask for forgiveness and plead guilty.

Ntamuhanga escaped from Mpanga prison in Nyanza District, Southern Province, on October 31, 2017, and registered as an asylum seeker in Mozambique in February 2018.

According to a blog post published by Ntamuhanga and several sources close to him, three of his brothers were reported missing in 2016. A family member told Human Rights Watch that they are still missing. Human Rights Watch was not able to independently verify the circumstances of their disappearances.

Mihigo was released in September 2018 after a presidential pardon. Afraid that state agents, including the head of police, Dan Munyuza, who continued to pressure him, would try to kill him, he attempted to flee Rwanda in February 2020. The police reported that they found him dead in his cell four days later, claiming that he had “strangled himself” to death. Rwandan authorities failed to conduct a credible, independent, and effective investigation into his suspicious death in custody.

Kidnappings and Forced Returns of Rwandan Refugees

A number of Rwandan victims of attacks abroad have been granted refugee status in the country to which they had fled in recognition of the risks they faced in Rwanda. Rwandan refugees or asylum seekers who are known to be political opponents, critics, or outspoken journalists, are particularly at risk. The fact that recognized refugees or Rwandans who have taken on a second nationality have fallen prey to such attacks has heightened fears among exiled Rwandans, who now believe that no one is out of reach.

The most recent, high-profile case is that of Paul Rusesabagina, who was the manager of the Hotel des Mille Collines, a luxury hotel in central Kigali where hundreds of people sought protection during the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. After the genocide he fled Rwanda, fearing for his safety. He later became a fierce critic of the government of Rwanda and co-founded the opposition Rwandan Movement for Democratic Change (Mouvement rwandais pour le changement démocratique, MRCD), whose armed wing has claimed responsibility for several attacks in Rwanda’s southern province since 2018.

Rusesabagina’s arrest and detention in August 2020, which started as an enforced disappearance, falls within the same pattern of abuse and raised grave concerns over his ability to receive a fair trial in Rwanda. Rusesabagina, now a Belgian citizen, was living in the United States when he traveled from the US to Dubai, United Arab Emirates, on August 27. He was forcibly disappeared on or about the evening of August 27 until the Rwanda Investigation Bureau announced it had Rusesabagina in custody in Kigali, Rwanda, on August 31. Human Rights Watch has documentedseveral fair trial violations since his trial began on February 17, 2021.

Some Rwandan refugees and asylum seekers have faced security threats in their country of asylum. Armed men abducted Joel Mutabazi, a former presidential bodyguard in Rwanda with refugee status in Uganda, in 2013. He was put on trial in Rwanda and sentenced to life in prison after a military court found Mutabazi guilty of terrorism, forming an armed group, and other offenses linked to alleged collaboration with an exiled opposition group and the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), a predominantly Rwandan armed group operating in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo that consists in part of people who took part in the 1994 Rwandan genocide. In the past 10 years, numerous Rwandan refugees and asylum seekers in Uganda have reported to Human Rights Watch a range of incidents, including personal threats by people they know or believe to be Rwandan, attacks on their homes, beatings, attempted abductions, and, in the most serious cases, killings, or attempted killings. Some have also reported being threatened and intimidated by Rwandan diplomatic representatives in Uganda.

Another notable case is that of Norbert Manirafasha, a political opposition activist and a registered Rwandan refugee, who was abducted by Rwandan intelligence agents in April 2014 in Goma, eastern Congo, and taken to Rwanda the same day. At the time of his abduction in Congo, Manirafasha was a refugee registered with UNHCR. This status should normally provide refugees protection under international law. He told Human Rights Watch he was tortured at Kami military camp, a notorious torture and interrogation center outside of Kigali, and forced to confess to working with opposition groups and the FDLR. He was sentenced to life in prison in Rwanda, although he told the court he had been tortured into making a false confession. The judges did not dismiss his earlier confession, even though he stated it was extracted under torture, nor did they order an investigation into his allegations.

Source: HRW