Yirga Gelaw Woldeyes, Curtin University

In early April an exhibition called “Maqdala 1868” opened at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. It’s comprised of treasures looted from Ethiopia, and so contributes to the ongoing controversy and debate about treasure ownership.

In the case of Ethiopia, what is important in this controversy is the fact that the question of ownership is linked to the question of memory: whose story should be remembered through these treasures?

As the name “Maqdala 1868” suggests, the stolen treasures are incorporated into the narrative of the British imperial war, to tell a story of how the British sent a large army to free their citizens from a savage king called Theodore in 1868. A century and a half after the battle Ethiopia’s stolen treasures are still used as war trophies, their meaning forever defined with the abandoned name of a short lived imperial fortress at Maqdala.

But for Ethiopia, there is no connection between the Maqdala war in 1868 and the stolen treasures at Maqdala. The war was imperial aggression against the King of Ethiopia. The stolen treasures amount to pure vandalism, a theft of knowledge and a crime against the current Ethiopian generation who are dispossessed of their intellectual heritage and history.

It’s this final meaning of “Maqdala 1868” that the British readily ignore.

Rewriting the Maqdala 1868 narrative

The Maqdala expedition is popularly known as a campaign for the release of British prisoners. But at the same time, a large army of “scientific” staff were sent to bring knowledge and treasures from the country.

The acting director of the British Museum, Richard Holmes, was already preparing to take manuscripts for his collections. Henry Stanley, the architect of Belgian King Leopold’s hellfire colony over the Congo, joined as a reporter. The Army under Captain Napier was “the biggest yet sent from Europe to Black Africa”.

Ethiopia began a new industrial revolution ten years before the battle. King Tewodros began manufacturing cannons and mortars, and constructing boats, roads and carriages. The National Library was established with an extensive collection of manuscripts from all over the country. As a sovereign Christian king, Tewodros endeavoured to build fraternity with Britain and wrote several letters to Queen Victoria.

The British were not prepared to accept a black king as a sovereign partner. They ignored him until he arrested British diplomats who conspired with foreign enemies and wrote accounts of the king as a black savage. By the time the British forces arrived with the help of internal defectors, Tewodros tried to solve the conflict peacefully. He released the British captives and sent gifts to Napier’s soldiers as a gesture of friendship.

The official stated purpose of the campaign was the release of the hostages. But Napier was not satisfied. The British demanded the surrender of the King, but he refused. Tewodros committed suicide and the British went on a looting spree. The entire treasury was looted; the cannons and mortars he manufactured were destroyed. 200 mules and 15 elephants were needed to carry all the looted bounty. What couldn’t be taken was set on fire. Maqdala burned for weeks with countless destroyed manuscripts left scattered over the abandoned citadel.

On the way back, soldiers held auctions to divide the loot. Richard Holmes alone acquired 350 manuscripts for the British Museum.

The only son of the dead King, Alemayehu, was also taken along with the treasures. His unhappy life ended in exile at the age of 18. His remains are still buried at St George’s Chapel of Windsor Castle, despite multiple requests for their repatriation.

Creating knowledge dependency in Africa

Before and after Maqdala, many Ethiopian manuscripts were taken through clandestine and diplomatic means. Germany acquired hundreds of manuscripts and scrolls through collectors such as Johannes Flemming and Enno Littmann. The French sponsored the Dakar-Djibouti Mission that collected enormous African materials, including 350 Ethiopian manuscripts.

The collection of African materials was used to produce knowledge that fit with the European view of the Dark Continent. Having numerous manuscripts at their disposal, European scholars translated them into their own languages. Hiob Ludolf wrote “the new history of Ethiopia” without needing to travel to the country. He is regarded as the father of modern Ethiopian history.

Centres of Ethiopian Studies emerged in Europe with acquisitions of various Ethiopian manuscripts. Carlo Conti-Rossini listed about 1200 Ethiopian manuscripts spread across Europe during the early 20th century. Like the British Library, the French National Library has a large collection of Ethiopian texts. Recently, manuscript collections from Ethiopia have gone digital.

The collection of Ethiopian manuscripts is carried out in the name of saving the humanity’s endangered heritage. The V&A exhibition itself is portrayed as a show of human history. But Ethiopian books and other materials are not endangered objects. They are in great demand in the traditional education system. Some European professors use them to produce books.

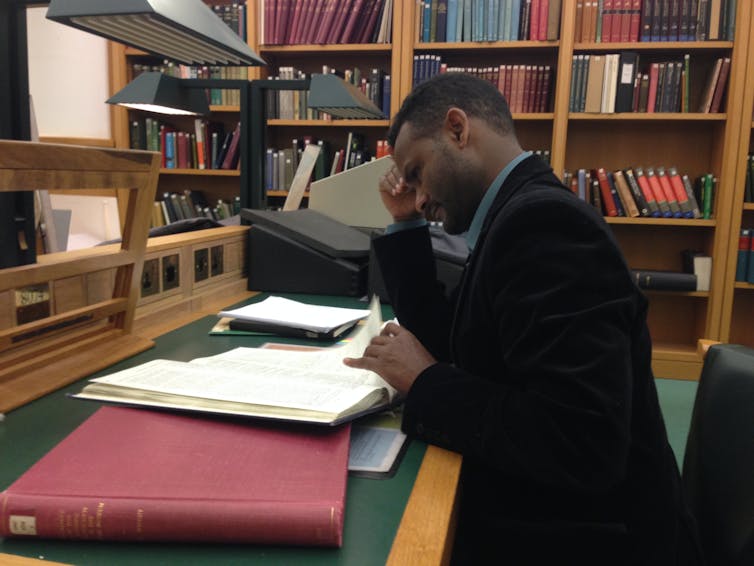

Ethiopians, however, who research about their past cannot access these manuscripts. We have to travel to European universities and museums for a brief glance at our own intellectual heritage. Even books that are digitised are not easily accessible. Those available online are hard to access from Ethiopia due to limited internet access. Texts written about Ethiopia are in European languages and are expensive to purchase. The British Museum’s proposal to loan the looted items to Ethiopia adds insult to injury.

The breaking of history

One of the consequences of knowledge dispossession is the breaking of history; the disintegration of the historical narratives that connect past and present generations of Ethiopians and other Africans. Like Egypt, Ethiopia provides the evidence that Africa is the mother of all civilisations.

Ethiopians wrote books before the British had an alphabet. They were the first to accept Christianity. Ancient Greek authors like Homer and Herodotus praised Ethiopia as a land of justice, wisdom and spirituality. Europeans’ legend eulogised Ethiopia as the land of a powerful Christian king called Prester John. Diasporic Africans sing of Ethiopia as the symbol of redemption, a holy land.

Many of the Ethiopian manuscripts which were looted from Maqdala provided evidence for this glorious image. Yet, the books and objects from Ethiopia are now stored in various European universities and museums with little hope for restitution. Scholarship produced by many Europeans professors and their Ethiopian followers often advance Eurocentric theories that delink Ethiopia from Africa by claiming, among other things, a non-African origin to Ethiopia’s civilisation.

This is a common practice of denying Africa of its own civilisational origin.

Ethiopians today are unable to produce their own knowledge, relying instead on imitating the content of western education. We study about the West more than our own country. English is used as a medium of higher education despite the fact that less than 1% of the population understands it. We are cut from our own history, and look to European historians like Ludolf to educate ourselves about our past.

![]() So the legacy of Magdala 1868 is about much, much more than just the looting of Ethiopia’s cultural heritage.

So the legacy of Magdala 1868 is about much, much more than just the looting of Ethiopia’s cultural heritage.

______________________________________________________

Yirga Gelaw Woldeyes, Lecturer of Human Rights, Curtin University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.