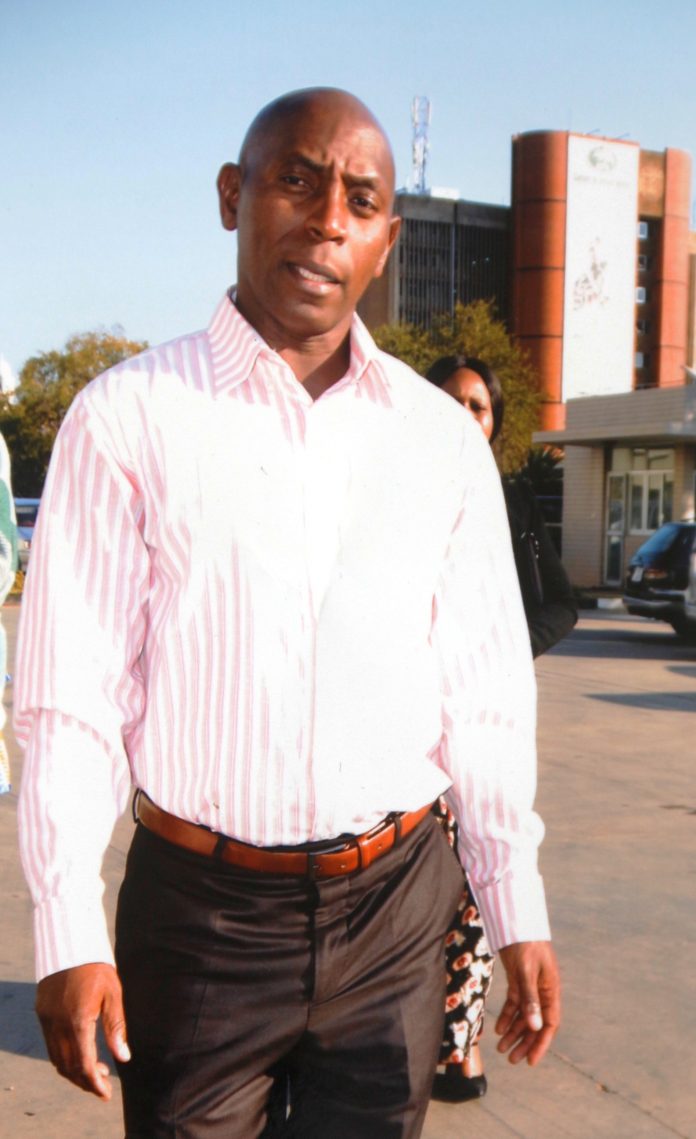

Rwanda born Burundian refugees in Zambia and Businessman Vincent Bagirishema , 44 died at UTH theater.

According to eye witnesses, around 20:50 on December 24th some 2 people entered in to the fence where Bagirishema was conducting his business of groceries, at Plot 3 Off Buluwe road, as he was busy lock the back door of his shop.

The wife who was in the family vehicle waiting her husband to finish , she came out the car upon seeing a shot gun that one had, ran away for her life and she heard shot gun.

Bagirishema was rushed to St John’s hospital and transferred to UTH since he was shot at the heart area, in order to die in the theater after 7 hours of operation according to some sources very conversant wit h the sad development.

Bagirishema who was born in Rwanda after his Burundian parents went to seek an asylum in Rwanda in early 70s at the time the elite Burundian hutu were being persecuted by the then regime, he arrived in Zambia in 1997, he survived by wife, and 2 daughters. The funeral is held at Ibex Twin Palm area.

Ends

P.S: Since early 2000, a serial killing targeting refugees of Rwanda origins have been observed as Edem Djokotoe was compelled to highlight it in the following column.

DO WE HEAR THEM WHEN THEY DO CRY

(By Edem Djokotoe in “SOUL TO SOUL” published in Zambia Post Daily news Paper 13th October 2006)

When I first met Jean-Claude about eight years ago, he must have been about 24 years old, maybe older. He had a hunted look about him, like a man afraid to even trust his own shadow. The way he cast furtive glances around during conversation gave you the impression of a man driven either by a deep sense of fear and by an intense paranoia.

One day he told my wife: there are people who want to kill me. Please, I need some money to move. Help me…

I can’t remember exactly how much she gave him, but Jean-Claude dropped out of sight for almost three months. When we saw him again, his story was still the same: there was a death squad out there with a list of people to exterminate and his name was on it. He needed money to relocate in a hurry…. At the time, the idea of a death squad in Lusaka seemed to be to pretty far-fetched, and I must confess, I began to suspect the young man of milking our sympathy for every penny he could get with his sob stories and his tales of bogeymen.

But when a friend of his was found murdered one day in one of the compounds in Lusaka, the possibility that Jean-Claude could have been telling the truth all along slowly dawned on me. To this day, I don’t know whether police caught anyone for the cold-blooded killing, but that’s how Jean-Claude dropped out of sight never to be seen again.

We tried to trace him, but we didn’t even know where to start from. We prayed and kept our fingers crossed that wherever Jean-Claude was, he was alive and well.

A year or so later, we got a phone call at around 0520 hours on Christmas Day. At the other end of the line was Jean-Claude. He was calling from Cleveland , Ohio US to wish us a Merry Christmas. It was a very short phone call, but he sounded so upbeat and so full of beans that we couldn’t help but catch the contagion of his infectious high spirits. We learnt that he’d managed to get into university and had found a part-time job.

The fact that he was safe and sound made us happy, but most of all, we were touched that he not only remembered us, but went out of his way to call us on Christmas Day. Things like this have a way of etching themselves indelibly in one’s album of memories…

But who exactly is Jean-Claude? Well, he was a Rwandese refugee my wife and I befriended by chance. His parents and his siblings were killed in the bloodbath History will remember as a genocide in the tiny central African state. When the bloodshed started, he was at university. Can’t remember what he said he was studying, but when we met survival, not tertiary education, was the main thing on his mind. But for some reason he felt unsafe, even in a refugee camp.

His fears of the likelihood of an untimely death at the hands of a death squad were heightened when Rwandese President, Paul Kagame came to Zambia a few years ago. Shortly afterwards, his friend was murdered, forcing him to flee Zambia for a safer haven.

Jean-Claude may be safe in the US , but sadly, many of the friends and compatriots he left behind in Zambia are not. Recent events seem to suggest that Rwandese refugees in Zambia today have every cause for alarm. Figures show that there are less than 4,000 Rwandese refugees living in Zambia , with a 1,000 living in Lusaka in 200 households. In the past six months, 25 of them have been targets of armed attack. Five of them have been killed in what the Rwandese community say are not random acts of violence but part of a carefully orchestrated plot to exterminate them systematically.

Apparently, the recent shooting to death of a Grade 12 Kamwala Secondary School student was part of a botched hit on a Rwandese family, a mother and her son, who fled from a gang of armed thugs who chased them from Kamwala Site and Service on 21 September this year.

The incident, my investigations revealed, took place not too far away from St. Patrick’s bus stop on Chilimbulu Road . It was almost the same spot where another Rwandese refugee had been brutally murdered a few days earlier on 17 September 2007. His name was Boniface Nyirishema and he was shot dead in the presence of his customers at his container tuck shop just opposite St Patrick’s bus stop in Kabwata. Nothing was stolen.

Three months earlier, on 13 June 2007, Thomas Kadoyi, another Rwandese refugee who was living in Jack Compound, was shot dead in his grocery shop. Again, nothing was stolen.

In the early hours of 13 May this year, an elderly couple in John Laing compound was attacked by armed criminals. The wife, Francoise Musabyemariya died instantly of gunshot wounds. Her husband survived the attack but was seriously injured in the process.

But Anaclet Hitimana, a Rwandese refugee of New Kanyama, was not so lucky. He was beaten to death by unknown people on 8 April 2007.

The regularity of these murders, not to mention the manner in which they have been carried out, convince members of the Rwandese refugee community in Lusaka that these killings are not coincidental and that they are part of a sinister plot which could probably have been hatched in and orchestrated from the country they left behind. They feel that the 1997 Extraction Treaty between the Zambian and Rwandese governments and the repatriation campaigns of 2002 were premature because neither addressed the pervasiveness of the insecurity that hung menacingly over their heads like a storm cloud.

Their suspicions and insecurities aside, one would expect that homicides taking place in a sovereign state, even if it involved foreign nationals, would be confirmed by the police. Not only that. A trend analysis, the same kind law enforcers use to determine from the pattern of a crime whether it qualifies to be tackled as a serial crime or as isolated incidents should have revealed that something was wrong somewhere. Agreed, Lusaka may not be Johannesburg where so many people are killed every day that you’d think they were broilers being slaughtered for some fast-food outlet, but even so, the murder of even one individual should cause enough of a social ripple to warrant some media attention. However, for whatever reason, the increasing number of Rwandese deaths does not seem to be stimulating the proverbial journalistic curiosity and getting media professionals to start what could be impact-making investigation. Of course, five murders and 25 armed attacks in six months may not be exactly agenocide, but suppose it is a harbinger of something bigger and more sinister? We won’t know until we ask some tough questions, will we?

For instance, how was it possible for Agnes Ntamabyariro, a former Rwandese Justice Minister to be kidnapped from Zambia in 1998 and, days later, find herself incarcerated in a prison in Kigali , strangely at a time when there was an Extraction Treaty in place between Zambia and Rwanda ?

Curiously, news of her kidnapping did not make headlines in Zambia, though details of the incident cropped up during an International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda session in Arusha in Tanzania during the trial of Bernard Ntuyahaga, a man charged for “crimes against humanity” and for his part in the murders of 10 Blue Helmets and other high-ranking Rwandese.

Developments like these suggest that there is a lot happening that we do not know about. With regard to the recent spate of murders where the victims have been Rwandese, police referred all questions to the chief government spokesperson, Mr. Michael Mulongoti and to the Minister of Home Affairs. They said given the gravity of the fears and suspicions of the Rwandese refugees, only government could comment on them. “The things they are talking about involves our relations with another country and because of the diplomatic implications, it is better you get the chief government spokesperson to confirm the deaths,” the source from Zambia Police Service headquarters said.

Personally, I found the response most intriguing. Not so long ago, when a senior Zimbabwean police officer died in a Lusaka hotel under very strange circumstances, the incident made headlines and got the Inspector-General of Police himself to issue a statement, even if all it did was refute a Post newspaper report. How much of a diplomatic incident all this caused I do not know, but what will be important to know is what the Zambia Police Service makes of all these murders.

From what I know, when a nation grants refugee status to people, it assumes some responsibility for their physical security. It is mainly for reasons of physical safety and security that refugee camps and settlements are restricted areas, places one cannot go without permission or clearance from the Ministry of Home Affairs. That is also why there are police checkpoints at the entrances of refugee camps and settlements.

Admittedly, when refugees live outside camps and settlements, it puts them on the same footing as the rest of us who are off the police radar screen most of the time, if not all the time. In short, it is practically impossible for the police to be everywhere and to watch everybody’s back. However, when murders happen at the rate at which they have, the public needs answers.

To this end, it would help if the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Country Representative of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees instituted investigations into the armed attacks with the view to finding out the identities and motives behind them. It would also help if these offices gave some reassurances to the refugees that their security and physical safety would not be left to chance.

But not everyone is optimistic. Refugees like Cesaire, a university lecturer before he fled his country, explains why circumstances have taught them not to keep their hopes up. “Being a refugee is an unjust social sentence for which appeal is not an option.

“The first lesson I learnt as a refugee is that when one door closes unconditionally, another door opens with conditions. Asylum comes as a non-negotiable, a non-committal contract, a fragile status, a big favour from the host country which you accept with gratitude. Asylum gives you hope of physical safety, a feeling that you will see the sun rise again, but you soon discover that your only real companion is your own vulnerability…