“My life is this. I can no longer move without being followed. I am obliged to have tinted windows to protect my interlocutors. I don’t visit my family and friends anymore; I don’t want to put them in danger. I live alone, I cannot have a woman in my life, and I will never have a family of my own. I don’t even know if I’ll still be alive in a year. I have nothing more to lose by talking anyway; you can even write my name. He has already lost everything. His story went around the world, when Amnesty International and Reporters without Borders were moved by his case. After publishing articles that criticized the ruling regime, he was brutally beaten in the street and left for dead. At the mention of the RPF, his voice breaks. He shows me his scar on his skull, which was cut with a knife. At the end of the interview, which will last the day, I am seized with panic terror. He looks at me gravely, points to the MP3-microphone resting in my palms. “How do you feel now that you have my life in your hands?”

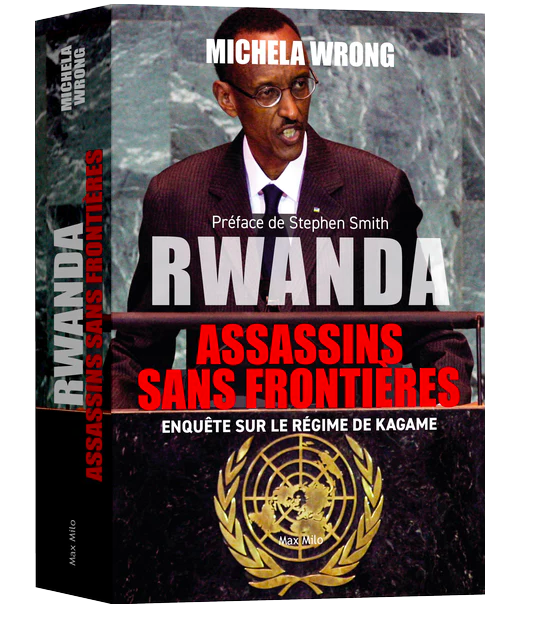

The owners of a Brussels Restaurant which should receive the conference of the courageous journalist Michela Wrong on her book recently published and which denounces the assassinations that the Kigali regime plots daily throughout the world declared being the subject of threats from people remotely sponsored by Kigali.

Assassinations without Borders

Since its conquest of power, the “killing machine” of the RPF plans and executes assassinations targeting any opponent or critic against it and its henchmen are deployed all over the world. The illustrations are legion and the process is taking its course. Former Rwandan Interior Minister Seth Sendashonga was shot dead in Nairobi 25 years ago today, on the orders of the RPF. Instead of apologizing, Paul Kagame actually bragged about it publicly. It was the same for Colonel Lizinde Theoneste and the trader Bugirimfura; Colonel Karegeya Patrick former head of foreign military intelligence strangled in a South African hotel by Kigali henchmen. General Kayumba Nyamwasa whose double attacks failed; Minister of Justice Nkubito Alphonse Marie; What about Gasana, former general manager of the Rwandan development bank then exiled in Mozambique but a member of the RNC. Seif Bamporiki, Revocat Karemangingo, Generals Mudacumura Sylvestre and Mugaragu Leodomir, General Stanislas Nzeyimana, General Musare, Ignace Murwandashyaka, former Trade Minister Uwiringiyimana Juvenal in 2005, Charles Ingabire in Kampala, Colonel Cyiza Augustin, Ben Rutabana, MP list is long. Opponents killed inside the country are also countless: André Kaggwa Rwisereka, Rwigara Assinapol; Kabera Assiel; many supporters of Madame Ingabire Victoire’s Dalfa-Umurinzi party; Ntwari Williams; Dr. Twagiramungu; Bukuru Ntwari; Kizito Mihigo; lawyers Mutunzi Donat and Toy Nzamwita, Dr Raymond Dusabe murdered in Cape Town in Africa; Monsignor Misago Augustin; Father Karekezi Dominique; General Dan Gapfizi; Colonel Ngoga Pascal; Colonel Bagire; Major Birasa; Major Sengati; the various religious of the Catholic Church in 1994,1995,1996,1997,1998 including the three bishops in Gakurazo;

A climate of terror where spies abound

The journalist reveals truths that other Rwandan intellectuals know silently. In 2004, Rwanda had only one national human rights NGO, LIPRODHOR, which was still critical of the government. When the latter was accused of harboring genocide “ideologues”, other national human rights NGOs remained silent, because they were already muzzled. Now, Rwandan human rights NGOs rarely investigate or document violations committed by the state, preferring to focus on abuses perpetrated by non-state actors (eg domestic violence). They avoid vigorous advocacy for human rights and focus on non-confrontational activities such as humanitarian assistance and human rights education and training.

In addition to this gag, certain pragmatism on the ground is invoked by organizations that often work together with small local partners and that are in contact with the population. These organizations then face a dilemma, namely whether to rise up against the regime and leave the population to themselves for good, or accept compromises. Given the importance of this point, the way in which journalistic cooperation organizations respond to this dilemma will be the subject of particular attention in the conclusion of this book.

Analysis:

if one wants to survive or avoid prison, one is silent in a country everyone suspects his neighbor

State-owned journalism

In Rwanda, the press has traditionally been a relay of information from the top to the bottom and not an agora allowing the expression of public opinion in a democratic society. According to the HCP (2004, 56), Rwandan titles, launched hastily without market research, give the impression “that one writes for oneself instead of writing for one’s readers”. The omission of prior segmentation of the country’s population makes any promoter of a newspaper unable to determine a target readership. The advertising market is almost non-existent which could lead to a better knowledge of an audience-consumer. Also, journalists, considered as spokespersons for the authorities, arouse mistrust. Journalists, for their part, take refuge in ease, contenting themselves with relaying official sources.

Good journalist vs bad journalist

However, the criminalization or not of journalists in the context of mass abuses can have an effect on the subsequent accountability of the journalist. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, where the criminal responsibility of the media has not been sanctioned by an international court, journalists have more credibility to express their desire to control entry into the profession by themselves. In Rwanda, local journalists have to bear the brunt of the guilt associated with journalism, which is associated with the effect of potentially hateful propaganda. The hate media paradigm, which is acutely reflected in ICTR judgments and in Rwandan texts, is dominant in the media sector. The response to this school of thought is twofold. Politics responds with a containment of presumed irresponsible media. The cooperative movement generally responds with training actions aimed at building responsible peace media (acting on transmission rather than reception).

Another observation: ethnicity, although concealed from the eyes of foreigners, weighs heavily on the current development of the media. This categorization into peace media and hate media, supported by the ICTR, has its consequences on the stereotypes (including ethnic ones) that will be attached to local journalists. In fact, this schematic opposition between “good” journalism and “bad” journalism will force local journalists to define themselves according to predetermined models closed in on themselves. Such a quest for identity facilitates the establishment of a logic of confrontation, gatherings around a closed and exclusive identity being structured around a raison d’être. However, there is no definitive identity, only a situational one: we can argue with a person and share segments of this person. One of the forms that the repression of conflict takes is precisely its formatting according to well-defined identities and in opposition to each other. Conflict makes it possible to think in terms of situation rather than identities, in terms of multiplicity rather than “sameness”, in terms of function rather than essence, even in terms of process rather than individualities.

Conclusion

Anti-Rwandan publications exposing the politics and diplomacy of Rwanda whose authors are foreigners are more dangerous for this regime than those from nationals that could easily be partisan. When the critical author is Tutsi, he is accused of embezzlement of public funds or rape de facto tarnishing his image; when it’s a Hutu, he/she is genocidal revenge or ideologue of the genocide and the regime gets off the hook easily. But when the critic is a foreigner, who has carried out his objective research which has finally unmasked the dignitaries of Kigali, the counter-offensive proves to be an arduous task and to prevent him from convincing the international community, it is necessary to resort to the last solution: his disappearance. This is what happened to Professor Jean Philippe Kalala Ometunde the Egyptologist who disappeared after having criticized the aggression of the Rwandan army against the DRC; THE Ghanaian journalist Komla Dumor in 2014 was also struck down by a sudden attack just 4 days after having energetically interviewed the Rwandan ambassador in London on the assassination of a former head of foreign intelligence services and dissident of the Tutsi supremacist regime in South Africa ; Reverend Christopher Mtikila, the Tanzanian politician who in 2015 revealed and denounced on Tanzanian television the ongoing project to create the Hima-Tutsi empire in the African Great Lakes region. As a result, intellectuals like Charles Onana, Kémi Seba; Lewis Mudge, Bernard Lughan, Serge Dupuis, Peter Erlinder, Philip Reyntjens, Michela Wrong whose pen despite its objectivity disturbs the power of Kigali should think about protecting themselves because Kigali’s henchmen are scattered all over the world.